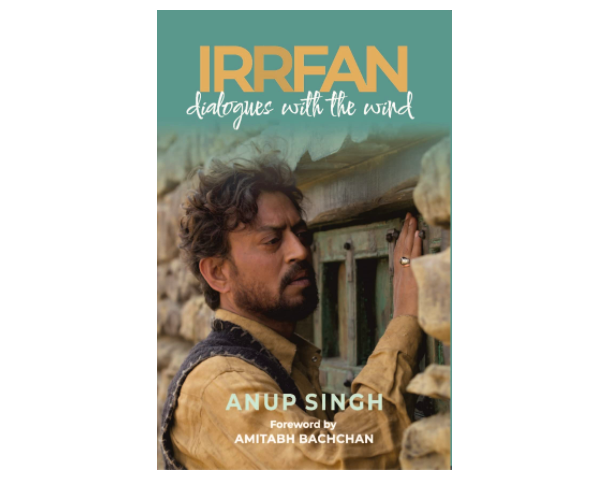

Noted filmmaker Anup Singh recently wrote Irrfan: Dialogues with the Wind, a book that dwells on his friendship with the acclaimed actor Irrfan Khan. Singh also made two movies—Qissa: The Tale of a Lonely Ghost (2013) and The Song of Scorpions (2017) with Khan. Born in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, Singh’s films have won numerous prestigious awards. He graduated from the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, in the mid-eighties and lives in Switzerland. Arvind Das spoke with Singh about his connection with Irrfan and how cinema can bring us closer to home. Edited excerpts:

Arvind Das [AD]: Let’s start with your book—Irrfan: Dialogues with the Wind. It reads like an elegy but is a celebration of life. Would you please share the kind of relationship you shared with Irrfan?

Anup Singh [AS]: Every time you ask me this question, my answer would be different! That was precisely the excitement and the challenge of being with Irrfan—he was ceaselessly different. As a person and actor, he was always attempting to seek, in every object, person and thought, a path to grow. Just as he refused numerous roles because they were too similar to what he had done before, he came to a friend to surprise, to astonish, to always initiate something new. I think this is what we enjoyed and cherished deeply about each other. Every time we met, we would carry with us a thought, a gesture, a poem, a stone, a story, which, we hoped, would fill the other with wonder. We were passionately committed to the expansion of each other’s experience of life. He might, for example, bring me two lines from Mir Taqi Mir:

‘dekh to dil ki jaañ se uthtā hai

ye dhuāñ sā kahāñ se uthtā hai’.

[Check if it rises from the heart or the soul

where is this smoke rising from?]

And I might bring him a sequence from Yasujiro Ozu’s film, Late Autumn, for him to see a simple, slow curve of the head by the great actress, Setsuko Hara. And then we could discuss these lines, this motion of the head for hours. The two films we made together would not have been possible without this strange, exhilarating friendship we shared.

AD: Watching Qissa, based on the partition, and The Song of Scorpions, I noticed they follow the epic form with a touch of melodrama. Also, your first film, The Name of the River, is a tribute to Ritwik Ghatak. Would you please say something about this influence?

AS: Some films burn your nervous system, and it never heals. Under the ash of whatever you believed, perceived, affirmed, there now constantly burns a flame that puts your every thought and action to test. All convictions burn away, except one: look again. Which means, think again, taste again, touch again, live again. And again, because every moment is new and, if you want to really live, every moment your life has to change. This is the gift (sometimes it seems like a curse!) Ritwik Ghatak’s films brought me. This, to me, is what the epic tradition suggests.

Think of black holes in space, for example. The gravity there is so fierce that not even light can escape. We, therefore, cannot see a black hole, but by paying attention to the distorting effect on what is around and on the light itself, we can hypothesise, deduce, surmise, guess—but never see. However, to even infer the presence of the black hole from the distortions around, we need to posit what is a distortion in space.

Too often, we are ready to judge a person by their name, what he or she wears. We accept what we are told about others as true—the cinema of Ritwik Ghatak questions such unexacting and easy attempts to understand our life. We, everything around us, are black holes. We need to be imagined, deduced, and dreamed about.

AD: In Ghatak’s movie Subarnarekha, I remember the question, ‘Yahan kaun nahi hai refugee—Who is not a refugee here’? Your films take it further till there is no end. For me, it’s a question of ‘mukti’ (salvation).

AS: Indeed, we are all refugees. Not because we have lost some mythical homeland. Our homeland is each other. Wherever we find ourselves in the making and, in our dialogue with ourselves and a community, we are home. This is a process and a dialogue. It will never end. All three films of mine seek to celebrate this sense of dialogue. In The Name of a River (2003), we open to possibilities like a river. In Qissa, we see how we destroy our world and damn ourselves by clinging to a singular belief. The Song of Scorpions is about how we choose to breathe on this earth. Do we just keep breathing our world in, taking and taking? Or do we learn to breathe out and give?

AD: You once told me about Dhrupad maestro Dagar sa’ab. Were you also trained under Zia Mohiuddin Dagar like director Mani Kaul? I ask because the music in all three films is something to ponder over, and it is central to the narrative.

AS: I never trained under Dagar Sa’ab. I have spent many long hours with him, journeyed with him and listened to him talk and sing and play the Rudra veena. He stays within me like his music. There is a call in his music, but in the way he sings or plays Dhrupad, he never establishes who that call is for. There are details in his music that stop time, even while there is a constant wandering away from any given goal. One phrase to another is a question and an answer but without an end. He can make us reside in a moment even as he prepares us to apprehend our fundamental homelessness.

Not simply for the music, but for the very moulding of the movement of my films, I am influenced by the tender yearning in Dagar Sa’ab’s music: his sense of evoking rather than installing an emotion, his play with details that hint at one rasa and lead us to another and at the end, in any rasa, he always leaves us with a sense of gentleness.

AD: You made The Name of the River in Bangla, Qissa in Punjabi and The Song of Scorpions in Rajasthani. I cannot think of a contemporary filmmaker who has made films in three languages. Could you easily have made them in Hindi or English?

AS: I had to fight a lot with my producers to do this! I believe every terrain impels certain tones and rhythms into how we speak. For example, a river is bound to encourage sibilance, as a desert might [link] a camel’s rhythm to a language. Drama rises, stands against and slips back into the environment. Language is shaped by the terrain, just as the landscape emerges in the language. Each gives scintillation to the other. I spend months living in the terrain where I plan to make a film. And everywhere I have been, I have seen how language, terrain, gesture, and the weight of an emotion are deeply connected. My attempt in my films has been to study this ecology. To see how it imprisons as well as frees us.

AD: In The Name of the River, we see water all around. Qissa is situated in the field, and The Song of Scorpions is set in the desert. Please tell me about the landscapes you pick for your movies. Do they signify something special?

AS: In many ways, the terrain embodies the theme of my films and the inner landscape of my characters. How the actors move, act (or not) in the landscape suggests the conflicts and balance within and between them. I believe that our residence in this terrain and our selves are profoundly connected. Water reflects. The surface hides depth. The Name of a River is a dialogue between what we see and so much more that we can only apprehend if we leave the shore of our preconceptions and enter the watery depths of history, legend, myth and ourselves. Qissa is a film about perspectives. What is close, and how did it suddenly become distant? The line of the horizon encloses me in my home, my field, my land, my country. And I want to think that the horizon line might not be a border, that the world does not end there. The desert is an infinity of barrenness and yet holds oases.

Legions have perished here, but lovers, poets and saints have consummated their passion or gained enlightenment. The desert holds both poison and balm. How we choose to see the desert perhaps tells us how we see ourselves. What do we choose to see—scorpion or song? Geography is the landscape of my film’s soul.