When I am absolute

at once

with the black earth

fire

I make

my nows

and power is spoken

peace

at rest and

hungry means never

or alone

I shall love

again

When I am obsolete.

( Audre Lorde)

The journey from being broken to complete is a story of healing from the wounds inflicted by the malice created around us, for us, aimed at breaking us. Despite this malice, in all ages and in every space, some people have been able to complete this journey. Each time they accomplished this feat, they left lessons for us which affirmed our hope that we, too, can break free of the shackles that bind us body and, primarily, mind.

Let me elaborate: The first act in the process of oppression is to kill our ability to imagine the future and demolish our hope of fulfilling our dreams. Seen this way, oppression is essentially a mental phenomenon. If it were a purely material phenomenon, then, as circumstances changed, a man would have changed himself to become free, human, complete. But we know this does not happen.

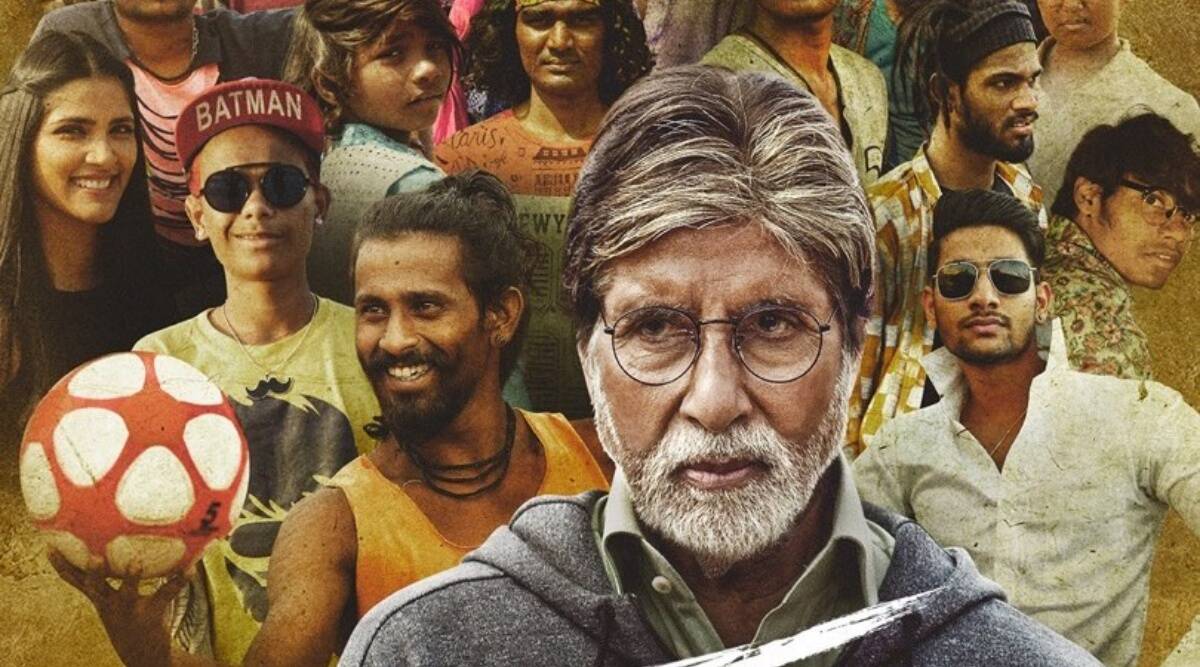

Nagraj Manjule’s recently-released first Hindi film Jhund breaks the internalisation among the dalit-bahujan masses about what constitutes a hero and heroism.

Man’s journey from being broken to absolute, complete, integrated with himself, is a process. It is an undeniably cultural act when films present their heroes to their audience. The hero figure influences our ideas about who a hero is and what heroism is all about. In Hindi cinema–Bollywood movies–the hero concept was always distorted; invented and presented as it is by and through savarna agency and savarna gaze, and imbued with savarna tastes. The heroes that then emerge are unreal, unconvincing, and lacking in the ability to connect with people.

Yet in the absence of other options, Bollywood could impose its savarna heroes on the dalit-bahujans. As a consequence, over decades, the dalit-bahujan masses forgot what the crucial elements of heroism are. To be a hero is to possess the ability to change one’s life. The vacuum created by forgetting this notion now gets filled with Bollywood trash! Dalit-bahujan people were made to believe that heroes do not exist in their lives or in themselves; that heroes exist only in films and are invariably larger than life. The lie was made into an everyday truth. Until recently, dalit-bahujans internalised this “truth”.

However, Nagraj Manjule’s recently-released first Hindi film Jhund breaks the internalisation among the dalit-bahujan masses about what constitutes a hero and heroism. He presents to us a hero each one of us can be, even though we had forgotten how to.

Dalit men are crushed by circumstances but possess no language to articulate or understand their oppression.

“Don” a.k.a. Ankush Masram (played by Ankush Gedam) is introduced in a slum as he emerges from the bathroom at his home beside a railway track in Nagpur. With scattered dusty hair and a bare chest, he wears a sleeveless jacket and walks with an unpolished stride. We soon learn he is frustrated with his alcoholic father and his reality. But his disgruntlement does not manifest itself easily in Don’s character. Rather, we find his life in the basti has a certain charm; such as when he is with his friends or when he gets involved in “illegal activities”. He drinks, smokes, sniffs glue, and steals mobile phones.

In the imagination of life outside of this movie, Don would be seen as an unworthy friend or lover, a broken man of our age. The weight of his circumstances have slowly deteriorated his hopes of imagining a new future for himself. Dalit men are crushed by circumstances, but possess no language to articulate or understand their oppression. They are often self-destructive. Even before they can take control over their lives, they lose it to alcohol or drugs. I have witnessed this process of breaking down so closely in my own basti that it took me no time to see how the real Don is.

Growing up in a dalit basti in Nagpur, I had a curious angst and hated most things around me. But I lacked the language to understand the source of my hate. It took me two decades to understand where my anger comes from. Only when I began to read and books became my companion, I could come to terms with my rage. I discovered I hated the circumstances in the basti more than anything. They never allowed new and fresh perspectives to enter our lives. A dalit basti is an assemblage of many things–but never hope. Living outside the basti for eight years helped me discover this reality. It also made me realise that people in the basti were not wrong—they were simply victims of caste. And one victim cannot heal another.

A dalit basti is an assemblage of many things but hope.

Hope needs to enter a basti to overcome the phenomenon of victimhood. I could not witness the arrival of this hope during my time living in one. It is only after I left that I could find any possible healing. In Jhund, hope arrives in the form of football for Don. Manjule’s treatment of the story and how he handles the element of hope in the life of a dalit man is an achievement in itself. For, he transcends our understanding of what it means to be born, to grow up and struggle lifelong in a dalit basti.

Jhund is an achievement in the discourse of liberation in India. What thousands of books failed to do, Manjule does with one film. He makes us believe in our own liberation without waiting for a liberator.

Football comes as a momentary escape from the darkness that surrounds Don in the Gaddi Godam slum in Nagpur. Vijay Borade (played by Amitabh Bacchan) is “Borade sir”, a football coach who happens to see Don and his friends play football with a plastic tumbler in the rain. He observes their footwork, their enthusiasm and senses their innate talent. He offers them money to play football for half an hour and brings them a real ball to play with.

Surprised that they would get paid to play football, Don and his friends start playing. What they did not realise is that playing made them forget their pain, the darkness in their lives, their humiliation in society. While playing, they began to feel a sense of belonging and worthiness. Borade is aware of this mental development among Don and his friends. At one point, he decides to stop paying Don and his friends for their games. So, one day, he doesn’t turn up with his football to the slum where Don and his friends waited for him. This was their last test—were these youngsters playing the game for money or had they developed a sense of belonging through football?

Jhund is an achievement in the discourse of liberation in India. What thousands of books failed to do, Manjule does with one film.

You thought right: Don and his friends turn up at Borade’s home and insist on playing football. Borade refuses, saying he can no longer pay them. The youngsters persist. Borade closes the door. Don says, “Sir, if you don’t want to give money it’s okay, at least give us a football to play with. I’ll take it on my risk.” By now, playing football has become an emotional concern for Don and his friends. They could not stay away from it for too long. To become aware of a longing for something is to be emotionally sensitive and accepting of the changes within you.

Don comes to terms with his emotional state through playing football. The sense of worth he feels in the game is a ray of light in his “dark” life. Playing football lets him leave the darkness far behind, even for a few fleeting moments.

This is just the beginning of Don’s journey in the world of hope.

To heal, men must learn to feel again, says Bell Hooks. Don, a dalit man, is on a newly-discovered path of hope that makes him believe he can be special too; a path that helps him redefine himself. He encounters trouble from the system—the police and local goons. Still he is keen to play on, but his past stands before him as an obstacle. He ends up a fugitive for a while, but stays on the path of feeling. Here is a situation that is real to dalit men: On the one hand, Don can almost taste a sweet future. On the other, the bitterness of his life pushes him towards the darker side. He is selected for the Homeless Soccer World Cup. But the police hold back his passport, the ticket to his dreams. He resorts to a legal battle and, once again, his caste becomes a stumbling block. Before the court of law, first he has to prove he is a human being, capable and worthy, only then does the issue of his passport even arise. Borade becomes a witness to Don’s humanity before the judge. The struggle is excruciatingly emotional.

In the past, it was usual to hear of dalits who don’t get government letters affirming their job positions, or whose offer letters arrive too late to secure a position. I have heard these stories very often from my elders. Such documents are way more important in the life of dalit men than anything else—especially if they are first-generation learners and dreamers. Don represents exactly this emotional dilemma and anxiety throughout Jhund. Caste society has discarded many Dons, pushing them to the shores of loneliness. But the path of feelings for dalit men is where the resurrection of their personhood lies. On this path, they turn loneliness into an avenue to rediscover themselves.

Your light shines very brightly

but I want you

to know

your darkness also

rich

and beyond fear

writes Audre Lorde.

When dalit men like Don re-learn how to feel, they are no longer afraid of the dark that makes up their lives. They begin to dream of the light. Don’s journey into this light is the beginning. Jhund marks the beginning of the dreams of a dalit man. This beginning is so real that everyone at the bottom of our society can relate to it.