“For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He had no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory. To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”—Elie Wiesel, Night.

Night, Elie Wiesel’s poignant memoir of the Holocaust and his time in an Auschwitz concentration camp, is an unforgettable reminder of man’s capacity to invent new ways to unleash brutalities over fellow human beings. It is about the alienation of human flesh, blood and mind from its human-ness. In history, those with the most deeply wounded hearts, who witnessed extreme suffering, were always the ones to reinstate our hope in the quest to survive. They encouraged us to change the history of hate and indifference into a future of love. The survivors of cruelty and darkness contribute light to the world.

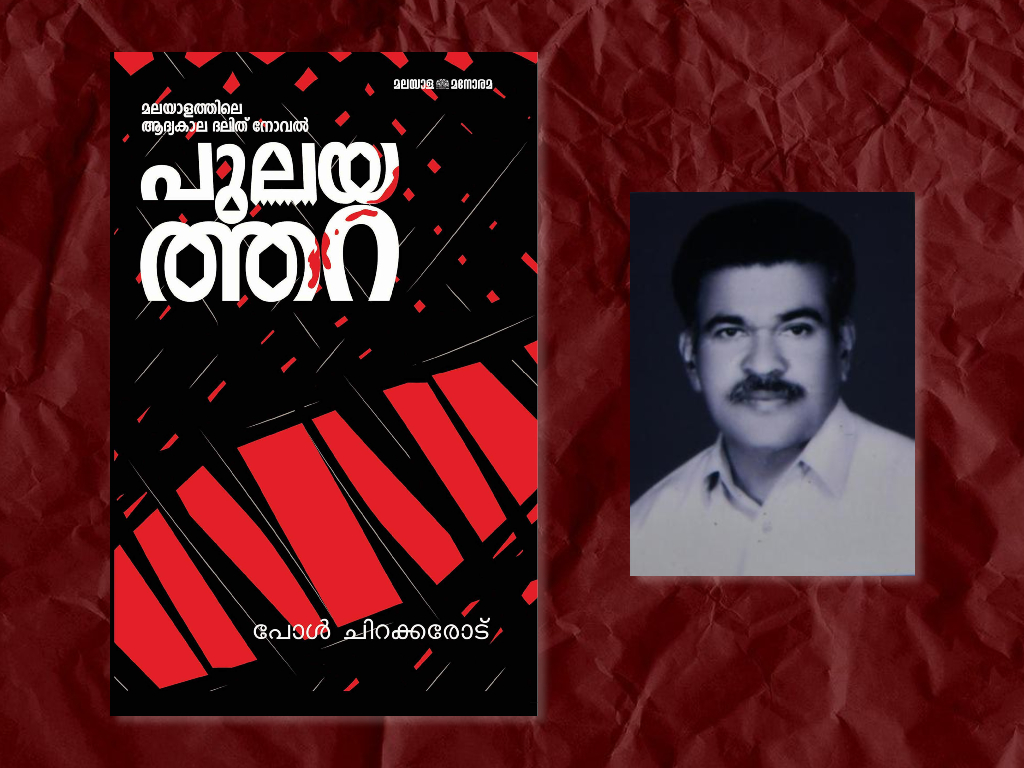

Carefully read Pulayathara, the novel Paul Chirakkarode published in 1962, to feel what I say. It will lead you to the world right next to you that, centuries ago, you refused to see. It will make you confront why and how caste is the invisible code of conduct in the everyday Holocaust of Dalits in this part of the world.

Pulayathara is the story of Dalit men in search of a home and love and their mental struggles while navigating life’s hardships. The tale of Thevan Pulayan (who is a Pulayar, an untouchable caste) is simple enough. It is about how he and his son Kandankoran shield themselves from the darkness of life, find new ways to keep dreams alive and feed themselves. The story’s dominant voice is survival and the quest to give that survival meaning. How does it feel to be treated like a refugee in the land of one’s birth, in the soil where one’s ancestors are buried? How does it feel to be akin to a refugee among people whose luxuries and leisure are the product of your labour, ill-treated and then persuaded into subjugation? This complex emotional trajectory is the everyday reality in the lives of dalits. Pulayathara elaborates on some aspects of this complex emotional trajectory.

Also read | ‘Home’ as a site of oppression: Pulayathara

Thevan Pulayan works in the fields of Narayanan Nair, who belongs to a feudal Savarna caste. Over the years, Thevan’s labour made Nair’s fields green and made it prosperous. For long sixty long years, Thevan nurtured these fields like his family, its crops and flowers like his children, and its soil like memories of his ancestors. Thevan belongs to these fields, but they are owned by Narayanan Nair.

One fine day, Nair expels Thevan and Kandankoran from the farm. Years of hard work and the prosperity they brought are overshadowed by one error. Nair, prejudiced about Kandankoran, never succeeded in seeing beyond a caste gaze and hires another Pulayar man to work his fields. Thevan’s years of labour are reduced to nothing because, in Nair’s feudal Savarna eyes, Thevan and Kandankoran were always untouchable. The house they were allowed to build in the fields, where they lived for years, was snatched from them. In one moment, Nair uprooted them and their desire to belong.

Which place in the vast universe can the father and son call home? The very sound of this question agonises Thevan deeply.

Expelled, displaced, uprooted from the universe of their memories, they seek shelter at the home of Pallithara Pathros—a Pulayar too—and his wife and daughter, Anna Kidathi. Pathros had got baptised and is a devoted Christian who works hard in fields owned by the Church. Pathros’s circumstances are no better than Thevan’s, except Pathros believes that as a devout Christian, he is no longer viewed as an untouchable.

Thevan and Kandankoran live on at Pathros’s house, but their sense of dignity refuses to let them be a burden for long. But they have nowhere to go. They own nothing except their history of displacement. They stay with Pathros while battling this dilemma. Unable to bear the idea of being a burden, one day, although with nowhere to go, Thevan and Kandankoran leave. By then, sowed in Anna’s tender heart was the seed of love for Kandankoran. He, too, has feelings for her. However, no matter how pure and beautiful their emotions, they are caged by material circumstances, poverty and the everyday struggle to survive. The quest for a life of dignity overpowers the desire to love and be loved.

Kandankoran and Anna are conscious of their situation. Love helps liberate us from the cruelty we inherit while growing up. Yet, our journey towards this liberation is determined by the extent to which we defy and resist the brutality around and within us. Caste society is cruel to Kandankoran and Anna, and they are aware of it. An untouchable, Kandankoran is an invisible man to society, except when his flawless labour is needed in a farm. To pursue the path of love before earning his dignity is something he cannot afford. He could not bear to be a nobody in his own eyes. It is cruel to be indifferent to that most beautiful feeling called love. Yet, for a while, he has no choice. He leaves with his father, now an older man.

Kandankoran cannot forget he has no place to call home. Yet, as an untouchable, he is also conscious that there is no home without love; a love which is returned. Home becomes his belonging; love becomes the act of being accepted. As an untouchable man, he cannot belong where he is not accepted, and cannot feel accepted where he does not belong. In his mind, Anna blooms as an idea of a place where he could feel at home and belong. They reciprocate their feelings after months of struggle. But he cannot marry her without becoming a Christian. For home and love, he gets baptised as Thoma.

Now a home shelters Kandankoran, and love gives meaning to his existence. They get married and have a child. Nothing changes in his life except, after still more struggle, he gets to live on Church land. Thevan does not like Kandankoran becoming Thoma. He sees in it his son’s alienation from his history. But what history do they have, if not of displacement and endless humiliation despite working hard for landlords and Savarnas? Kandankoran comes to terms with this reality—Thevan could not. That is why Kandankoran became Thoma.

Meanwhile, the dalit Christians recognise their humiliation and discrimination within the Church. They see the Syrian Christians (erstwhile Brahmins and Syrians) do not treat them as equals and decide to assert themselves. They create their own platform to raise their concerns, but Syrian Christians call it blasphemy. Thoma observes all this, unaffected. He never felt accepted among Syrian Christians, and his instinct guides him to his personal path of liberation. His unpleasant experiences after becoming a Christian make him wonder if religious conversion really could liberate those like him whom society, despite everything they contribute, perceives and regards as untouchable.

Thoma declares his decision not to baptise his son. It shocks Anna, but he is defiant and clear-eyed. “Edi, I am a Pulayar. I will live in the field. I will work for daily wages. I will stay where I can,” he says, “But I will send my son to school, educate him. I will not let him become some landlord’s slave. You wait and see.”

Thoma emphasises the words “Pulayar”, “fields”, “wages”. In his eyes, his identity is defined by these things; they are instrumental to his personhood. His becoming a Christian brought him only to bitter experiences. As a dalit man, he discovers his personality in the history from which he was displaced and humiliated. In it, he struggled but survived, and so, he realises, he can redefine the terms of his existence. He becomes the epitome of a generation of dalits who have decided to speak out, testify to their past, and commend its memory to future generations.