When one thinks of the term “partition” in the Indian context, it comes with varied connotations. While on the one hand, it carries a sense of freedom, democracy and liberty, on the other hand, it brings in the horrific repercussions that the people of the land had to go through. It isn’t a mere drawing of lines, it is rather a mutilation of the body. The politics of power and land cut across and the ones on the ground level are subject to numerous atrocities.

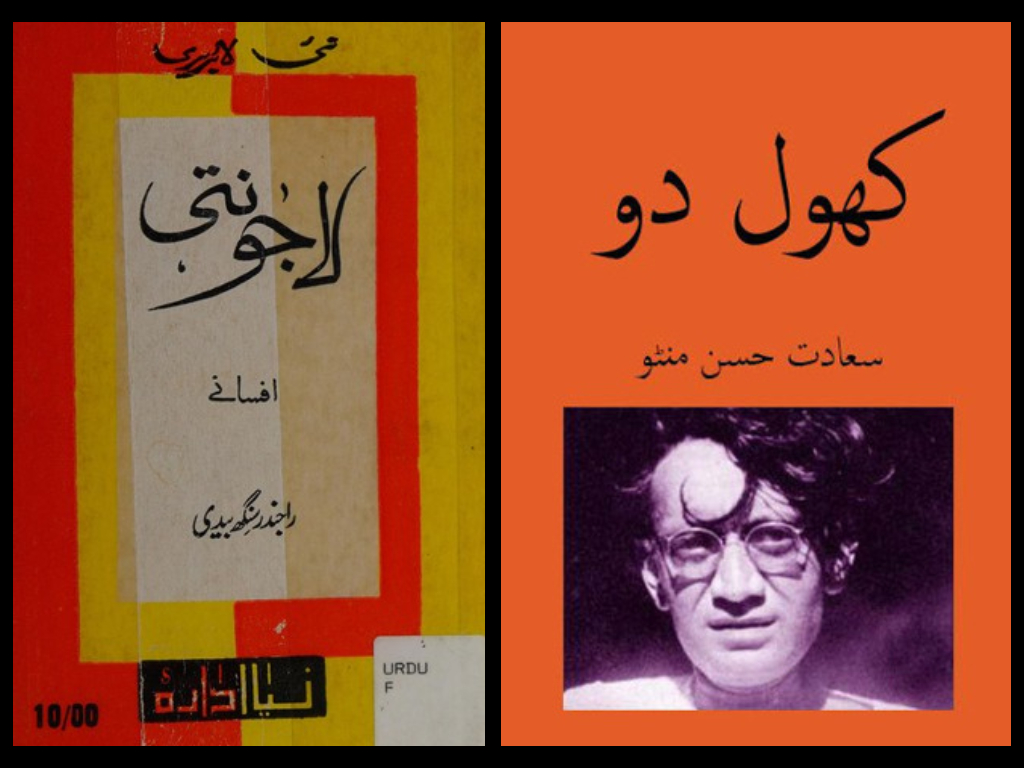

Partition fiction has inadvertently brought to fore the idea of violence that is inherently gendered. The metaphor of the country being a “Mother”, usually propagated in the mainstream of patriotism, has been completely deconstructed through the violence and torture meted out to the very women of the land. I aim to reflect on the idea of muted gender through the fictional narratives ‘Khol Do’ by Saadat Hasan Manto and ‘Lajwanti’ by Rajender Singh Bedi. Both of them narrativise the plight of women navigating the political economy of gender/reproductive economy placed at the intersection of religion and gender.

It is quite evident that women’s bodies are seen as a land that is freely available for depicting the “masculinity” of men. Partition not only mutilated the motherland but also shattered the notion of a mother as a nurturer. The sheer commodification of the female body, something that could be raped, paraded naked, mutilated, and battered in the name of religion is showcased in these narratives.

In ‘Khol Do’, Manto depicts the harsh circumstances that a young seventeen-year-old girl Sakina has to go through. She is abducted and raped repeatedly. The extent of her traume is so much that every time a man comes near her she inadvertently opens up her salwar. The aspects of honor are brought to the fore in this story. An adolescent girl is denied her dignity before she could even make sense of her own changing body. The symbolism imbibed in her dupatta reflects on the idea of how partition led to a double disrobing. Sakina loses agency over her own body just like the motherland no longer held a singular identity, her name divided, her body cut open and her honor disregarded.

The idea of trauma and silence is a pertinent factor to consider when it comes to the violence inflicted upon women during the Partition of 1947. Defining trauma, Erikson writes, “It invades you, takes over you, becomes a dominating feature of your interior landscape—”possesses” you… Above all, trauma involves a continual reliving of some wounding experience in daydreams and nightmares, flashbacks and hallucinations, and in a compulsive seeking out of similar circumstances.”

While Manto evades the normative structures and forces the reader to confront reality unmasked, Rajendar Singh Bedi brings in the notes of mythological justifications in his story ‘Lajwanti’ to argue that even though Sita stayed with the “other” man she remained “pure”. This particular trajectory traverses the idea of women being “impure” if they were abducted by men of other religions. During the partition, innumerable women were abducted by men of the opposite side’s religion. The negotiations to bring them back to their homeland reflect upon the sheer commodification of women. They are dehumanised; bought and sold like mere commodities available in the market by the men of both sides.

After the negotiations, when finally women come back to their own country, they have to face immense social stigmatisation. The physical and mental torture perpetuates even after they are brought back. The torn identity of the female self is reflected by Bedi in his narrative. Although Sunder Lal does not reject his wife Lajwanti, he ends up deifying her – a sacred woman devoid of her sensual being. Veena Das in her work Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary defines cultural trauma as “a dramatic loss of identity and meaning, a tear in the social fabric, affecting a group of people that have achieved some degree of cohesion.” We can thus infer that Partition not only divided the land but also defiled the socio-cultural fabric of various communities.

The aspect of muted gender is important in both the stories. In ‘Khol Do’, we see that Sakina does not express her pain but has rather succumbed to the way of the society. She utters not a single word. In Lajwanti we see that though Lajwanti is visibly healthy, hardly anyone tries to unearth her mental trauma. The idea of rehabilitation is only limited to physical health. She curls back into her limited world not voicing her side of the story.

The partition of 1947 that led to “forced migration…and conversion of women and children; families, communities, governments and political parties converging with the intent to “recover” and “restore” women to their “rightful” place; the figure of the abducted woman came to symbolize the crossing of borders as well as the violation of social, cultural and political boundaries,” argue Ritu Menon and Kamala Bhasin in their book Borders & Boundaries: Women in India’s Partition.

The aspect of the muted gender is evidently brought to the fore by Manto and Bedi in their respective stories. The coming together of the personal and the political placed at the cross-section of female identity is an attempt to reiterate those horrific tales, creating an all-around sensory impact on the readers. Silence speaks volumes and this is the strategy adopted by both the authors to highlight the void of female accounts of partition narratives.

Works Cited

1. Abbas, Dr. S.Z. “”To speak or not to speak?”1: Silence and Trauma in Rajinder Singh Bedi’s ‘Lajwanti’ and Sa‘adat Hasan Manto’s ‘Open It.” European Academic Research, vol. 3, no. 8, 2015, pp. 9179-9196. Research gate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301649143_To_speak_or_not_to_speak_1_Silence_and_Trauma_in_Rajinder_Singh_Bedi’s_’Lajwanti’_and_Sa’adat_Hasan_Manto’s_’Open_It’. Accessed 19 September 2021.

2. Bedi, Rajinder Singh. “Lajwanti.” Urduwallahs, February 2014, https://urduwallahs.wordpress.com/2014/02/22/lajwanti-rajinder-singh-bedi/. Accessed 16 September 2021.

3. Butalia, Urvashi. he Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Duke University Press, 2000. https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-other-side-of-silence.

4. Das, Veena. Life and Words Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. University of California Press, 2006. ucpress.edu, https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520247451/life-and-words. Accessed 16 September 2021.

5. Dey, Arunima. “Violence Against Women During The Partition Of India: Interpreting Women And Their Bodies In The Context Of Ethnic Genocide.” ES. Revista de Filología Inglesa, vol. 37, no. 2016, 2016, pp. 105-118.

6. Manto, Saadat Hasan. “Khol Do.” urduwallahs.wordpress.com, August 2014, https://urduwallahs.wordpress.com/2014/08/02/khol-do-saadat-hasan-manto/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CKhol%20Do%E2%80%9D%20is%20one%20of,the%20people%20of%20the%20land. Accessed 16 September 2021.