‘Huts without roof.

Huts without walls.

Huts ground to dust.

To ash.

Huts with broken bangle pieces’.

These were the opening lines of an essay on the Keezhvenmani massacre where forty-four Dalit agricultural labourers, members of the kisan union of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), were trapped inside a small hut and burnt alive in a village in the former Thanjavur district, the ‘rice bowl’ of Tamil Nadu. The author of the essay Mythily Sivaraman, then a young woman of twenty-nine years, visited the Keezhvenmani village in early January 1969, a week after the massacre, along with the veteran Gandhian activist Krishnammal Jagannathan.

In her essay — ‘Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani’ (published in Economic and Political Weekly, 1973) — Mythily recounted the events that had unfolded in the villages of Thanjavur, most notably the creation of Paddy Producers Association of landowners that countered the organized strength of the peasants and unleashed deliberate acts of terror such as the murders of leading peasant activists in the months preceding the massacre.

Mythily’s essay provides a chilling account of the events that culminated in the massacre on the night of 25 December 1968. Mythily engaged with the survivors and eyewitnesses who described the massacre in these words:

The heartrending cries heard far, far away; the bolted door; the burning hut surrounded by bloodthirsty murderers with lethal weapons; two children thrown out from the hut, but thrown back into the fire by the arsonists; six people who managed to come out through the burning hut, two of whom were caught, hacked to death and thrown into the fire; and the fire systematically stoked with hay and dry wood.

Mythily’s essay was an eviscerating takedown of the Madras High Court judgement (1973) that acquitted all the 25 accused in the murder case. She urged her readers to see the core of the conflict. The issue at stake was not the demand for wage increase by the agricultural labourers but their fight for unionization. Indeed, the wage demands were secondary, and the landlords may have even been willing to concede these, Mythily argues. It was the peasants’ fight for dignity and their claim to autonomous political organisation, reflected in their stubborn insistence that they would ‘fly the red flag’ in their village, that had rankled the landlords and provoked such a bloody retaliation.

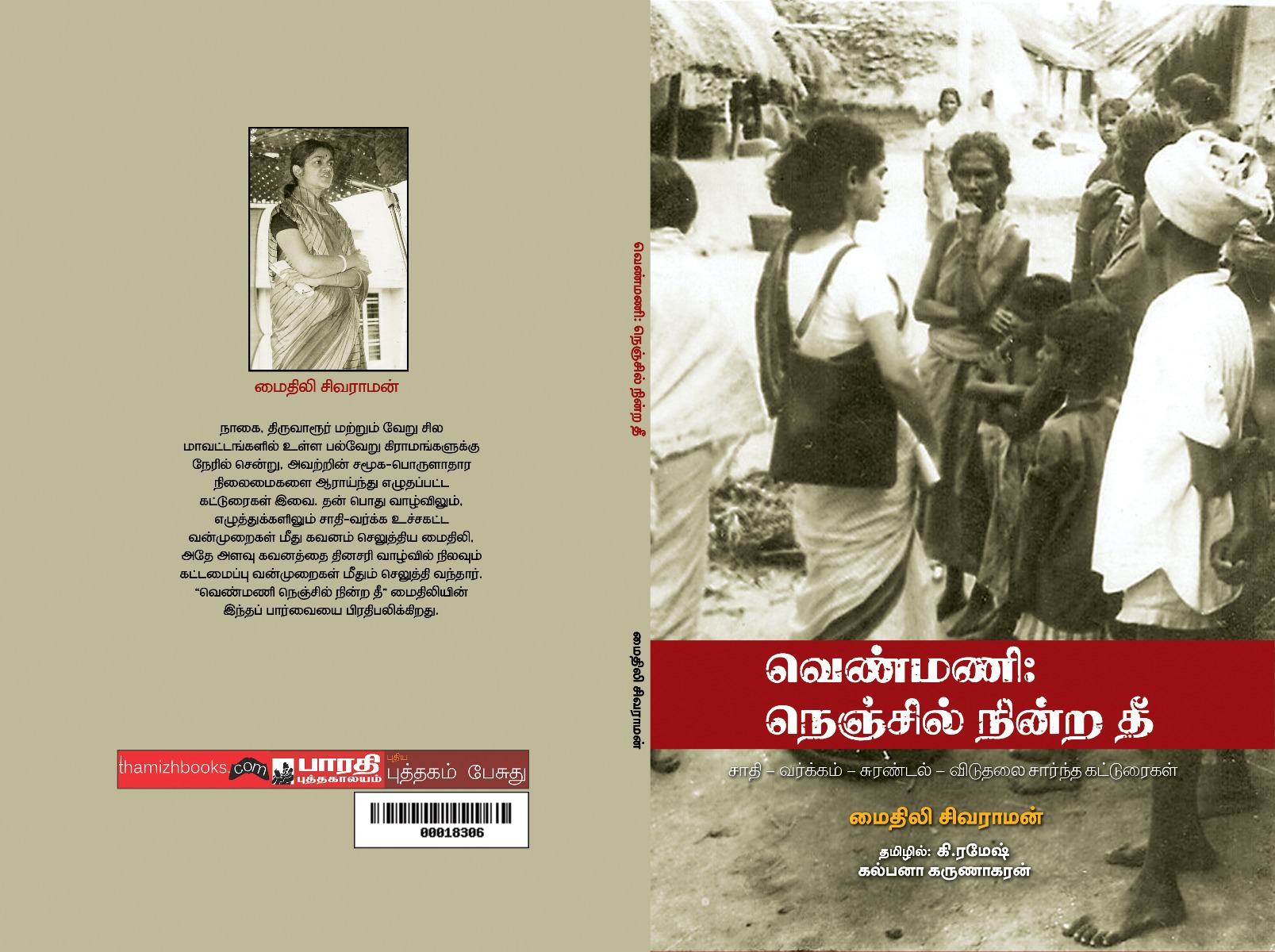

On 25 December 2021, the 53rd anniversary of the massacre, a book of Mythily’s Tamil essays that included her writings on Keezhvenmani was released in the village during the annual commemoration of the massacre. Written between 1969 and 1973, the essays in the Tamil book Venmani: Nenjil Nindra Thee (Venmani: The fire that burnt forever in the heart) were first published in English language newspapers and journals, including the Radical Review of which Mythily was then the editor[1].

In her political activism and her writings, Mythily had paid as much attention to the structural violence of ‘normal’ life in caste-class society as she had to its explosive manifestations, as seen in the Kilvenmani massacre. In keeping with this understanding, Mythily’s book included, in equal part, her essays tracing the rhythms of everyday life in Tamil Nadu’s villages and the constitutive logic of the caste order that shaped this life, stripping Dalits of their humanity and dignity.

The gender implications of what Mythily described were equally stark. As she notes in an interview that she gave to a Tamil journal in 1999 (also included in the book), it was women who bore the brunt of violent upheavals and reprisals, whether at Keezhvenmani or Nadukuppam, a fishing hamlet on the Marina beach of Chennai, when police clashed with fishers in November 1985 and subsequently subjected women to gendered verbal abuse and severe beatings with rifle butts, boots and lathis[2].

Of the forty-four burnt alive at Keezhvenmani — five were elderly men, sixteen were women, and twenty-three were children. The horror of the Keezhvenmani killings lit an everlasting fire in Mythily’s heart (as the title of the Tamil book suggests) and led her to a lifetime of political activism with the CPI(M). The massacre made her see that the social change she wanted to work for could not come to fruition without a more radical political-structural transformation.

Mythily had died earlier this year during the peak of the second wave of Covid. As one of the translators of Mythily’s Tamil book of essays, I was eager to attend the launch of the book[3]. As Mythily’s daughter, I wanted to re-visit Venmani, where her four-decade-long public life had begun. I had first heard of what happened at Keezhvenmani as a very young child when my mother narrated the story of the polladha pannaiyaru (the evil landlord), the child murderer. I had been to Venmani with my mother on two occasions earlier.

The first was on Pongal day of January 1992 when the village had gathered together. The spirit was festive, and sports events were on when we arrived. The word that Mythily Sivaraman had come quickly spread, and a crowd gathered to welcome us. I recall that we took a group photograph.

The second was a sadder and quieter visit. In September 2011, when we visited Keezhvenmani with the historian Uma Chakravarty, Mythily’s memory and her sense of time and place had been ravaged by Alzheimer’s dementia. I was preoccupied with ensuring that she was not too disoriented or exhausted by the journey. Standing beside the martyrs’ memorial, Uma Chakravarty reminded Mythily of what the landlords and their henchmen had done some decades ago. Mythily responded, loudly and clearly, ‘bastards’!

Neither of those trips prepared me for my visit this year, my first on the day of the anniversary. Festoons of red flags greeted the eye everywhere. The sight was something to see. Small pavement shops selling food and household items of everyday use had sprung up and dotted the 1.5-kilometre long mud road that branched away from the main road and led to the memorial, the massacre site.

A ten thousand perhaps or quite likely more had filled up the maidan, the large open ground adjacent to the memorial from villages and districts, near and far. It was impossible to count the numbers when large groups came in waves, paid homage at the memorial and departed, soon followed by more.

Peasants and agricultural labourers, industrial workers, IT employees, public sector employees, and students associated with the left and progressive movements came, carrying banners and shouting full-throated slogans. Many of them had brought along their families and friends to introduce them to a chapter of struggle in Tamil Nadu’s history.

In memory of the forty-four killed, Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) donated 44 sacks of rice to symbolize worker-peasant unity. CITU took on the responsibility of cooking and feeding the crowds who visited the memorial until the late hours of the evening. CPI(M) organisers informed me that over the years, a range of political parties, including those belonging to different shades of the left and the prominent Dalit parties of Tamil Nadu, also visited Keezhvenmani on the commemoration day.

Party members were not the only visitors who came to pay their respects. Large processions from the neighbouring villages marched into Venmani in a steady stream, bearing floral wreaths for the memorial and beating the parai (hollow drum). Men and women alike were dancing with gusto. Women and girls were in their Sunday best clothes. The carnivalesque atmosphere of the commemoration day bore the characteristic stamp of a thiruvizha (festival), a secular celebration in this case that honoured the dead, invoked their memory and celebrated the legacy of struggle they embodied.

A grand new memorial building under construction by the side of the older one was open to the public. The functional staircase allowed many to climb up to the large balcony to get a bird’s eye view of the maidan and the milling crowds. The formal public event was underway on a makeshift stage where books were released, songs sung, and speeches made.

Vanavil, a residential school in Nagai district for children from historically marginalized and itinerant nomadic communities, had brought its students to pay homage, as it did every year. The children were huddled together in a group inside the memorial, listening to Revathi Akka, the school’s founder, tell a story of oppression, uprising, and defiance.

Sitting with a team of young people from Chennai, we read aloud passages from Mythily’s book that had just been released, shouting to make ourselves heard in the deafening roar of the crowd pressing around us. Meanwhile, processions continued to pour in, some of the marchers dancing all the way from the arch that had been erected to mark the fork in the mud road winding towards Venmani.

On the way out of the village, we struck up a conversation with three young girls in their mid-to-late teens walking beside us. They were residents of a village close by and could not recall their first visit to Venmani. They had accompanied their parents since they were tiny tots. Their families had not missed a single anniversary event over the years. Now that they were older, they were here on their own. They had brought flowers, paid homage to the martyrs, wandered around the maidan and greeted their friends. They knew, of course, of how forty-four people had been pitilessly burnt alive for having asked for an extra measure of rice as wages.

Were their parents members of any political party, we asked? Did the girls know if the Venmani martyrs had been part of a political movement? No, they replied to both questions. They explained that they could not vote yet and had not given much thought to politics or parties so far. Of course, they would come back to Venmani the next year and the years after. No one could forget what had brought us here on this day. No one could remain unmoved by it.

Through the day, I met scores of friends and comrades of Mythily from the delta districts of Nagai, Thanjavur, and Thiruvarur who recalled her presence and work amongst them with great affection. In a national political climate marked by the spewing of hate and venom, the demonizing of ‘others’ and the absence of empathy, it appeared a sign of hope that so many across occupations, classes, castes, and communities had showed up to pay tribute, express solidarity and identify themselves with a heroic uprising of the oppressed. As I left Keezhvenmani, my heart was full.