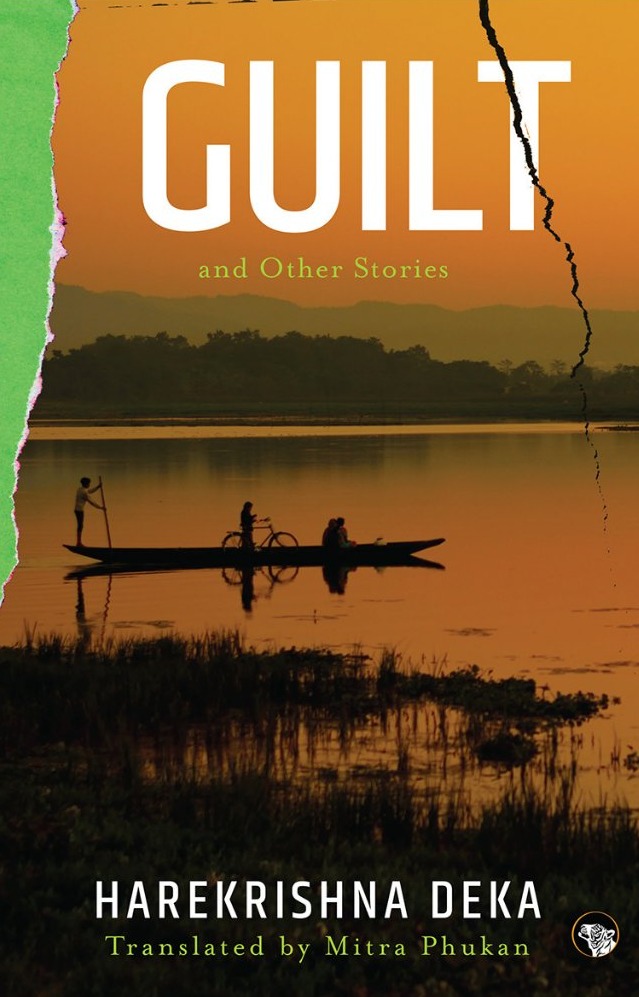

Translated into English by Mitra Phukan, Guilt and Other Stories, is a collection of short stories written by Harekrishna Deka over a span of several decades.

Through these stories, Deka gives the readers a searing vision of the human condition, even as he brings alive the unique landscape of Assam in unforgettable images.

The following is an excerpt from the story, ‘The Captive’.

Sitting on the bed, he took out the notebook from the satchel that he carried with him. For the last three months or so, he had been keeping this journal of his captivity. The youth had brought him this notebook when he had expressed the desire to keep a journal. Out of his total captivity of seven months, he had kept a record of his daily experiences for the last three months. He had also written down, as far as he had been able, a record of the time before. Those entries, of course, were from memory.

As soon as he closed the door from inside, a sense of captivity engulfed him. Now it was as if he had willingly made himself captive. But even this self-imposed captivity felt normal for him. So long as the door had been open, he had not felt like this. The murmur of voices from the other house had created the impression of some link with it. That link was now severed. The room was lonely and silent. There was no opening now on any side. He felt at peace after imprisoning himself.

By not remaining there, the youth who had said, ‘I shall remain outside,’ had placed the prime responsibility for his own captivity on him. As long as the door was open, he had had a sense of unease. What if his mind hindered his feet from discharging that responsibility? What if his mind tempted his feet: ‘The open sky is out there, there is freedom outside, go, get away!’

And what if his feet really went out through the door? What if they, his feet, refused to accept the bond of that unseen trust? But no, he had shut the door. He had accepted his captivity. He had accepted the discipline of the words, ‘I shall remain outside. And strangely, he felt at peace.

Rifling through the pages of the notebook, he glanced through the previous entries before writing down the experiences of that day. It had become a habit with him. to read about the events of the past almost every day. In this manner, he wished to preserve intact the memories of these days.

He had written down the experiences of the first day on the very first page of the diary. On that day, they had put him inside a house and locked the door from outside. ‘We shall be outside, don’t try to escape. How harsh, how frightening, the words had been that day! They had dragged him out from his own familiar world, and pushed him into another one. The memory of the moment made him shudder. That moment, when another vehicle had stopped before his own. Four gun-wielding youths had dragged him out from his car, and pushed him into the back-seat of another vehicle. That had been a terrifying moment. Later, however, he had realized that the logic of the youth’s world was not the same as the logic of reason in his own ordered existence. He had heard them say several words which he himself used, or had read. However, since he could not understand the tribal language, those remained gestures for him. But even those gestures had had the power to create a sense of fear in him.

They also used some bookish English and Assamese words. Nation, state, revolution, imperialistic power, national consciousness, government, public, freedom, rights in their world, the meanings of these words were completely different. The meaning of the word ‘security’. was also different in their world. This was because they. had their own interpretation of the law. The entity that he had always thought of as a ‘nation’ was not, for them, a nation at all. They had created their own nation. In their eyes, his nation was an imperialist power. He had assumed that he was a citizen of a free country, but they said that he was the lackey of this imperialist power. Those laws which he had always thought of as a haven of security, were perceived by them to be the means of state terrorism. Their act of kidnapping was, for him, an act of terrorism; but they viewed it as their duty to their nation. The government which he thought provided them with social and political security was for them an illegitimate government. It was, for them, but a sand bar across the mouth of a river, to be swept away by the flood-waters of revolution. He had read of many revolutions. But with the barrels of their guns pointed at his body, these youths seemed to aim the revolution at him.

They had reassured him that he himself was quite. insignificant. Their dissension was against the ‘illegitimate imperialistic national power. He had been taken hostage because he was a symbol of the repressive security arrangements of that government machinery. The national power accorded importance to symbols such as he, for that power was a repressive force. Repressive acts were carried out in the name of security. If the mask of security was lifted, that power would be revealed in its true self.

They had some demands to make of that machinery which called itself the government. (Some day, they would overthrow that power, but it would take time for the revolution to mature. Therefore, it was necessary for them to get the illegitimate government to accede to some of their demands in this way.) That other nation would grant them their demands, for it was to that imperialistic power’s self-interest to have him freed. Because if he died, the mask of security which that power used as an excuse would be ripped apart.

However, they had not presented their reasoning in quite that manner. From what he could understand of their language when they talked with each other, he had inferred this logic. He got the impression that the ideas in the world that he lived in were controlled by a kind of linguistic centre. It was as though both groups of people, the youths’ and his own, had what each one believed to be positive electromagnetic charges which, when they met, repelled each other. Even with his bureaucratic attitude (he was an important government officer) he could vaguely discern that both these worlds were deeply influenced by economic realities, and this had become intermingled with politics.

And he had been afraid. He could see no escape, no way out from the gulf between their world and his, or from the emptiness that enveloped him. For a long time, the meaning of their words, and their reasoning was hidden from him, like the words of a riddle. They did not inflict any physical torture on him at all. Though their manner of speaking was rough, they were not exactly disrespectful towards him. Once in a while, they also allowed him to exchange letters with those at home. But their way of thinking clashed repeatedly with his own. He had not been able trust them. He would feel as though, at any moment, the muzzles of their guns would discharge their bullets into his breast.

But even greater than this physical fear had been the tremendous mental tension that he had felt. The physical hardships that he went through were of course quite considerable. Every day, they had to change shelters. He had no settled place to stay in. Nightly, they would wander through fields, wade through the chest-high water of rivers, march through dense jungles and marshes. Yet he would have shrugged off these physical hardships if he had only been able to trust them. Pushing him into various rooms at night, they would stand guard outside.

Occasionally, they would push him inside with the words, ‘We shall remain outside. Don’t try to escape.’ Each word seemed weighted with ridicule, callousness, and cruelty. Each word seemed to express not just his own helplessness, but also that of the national power. As it wounded him, each word became synonymous with terror.

He had been unable to comprehend how a functionary could become the symbol of the government machinery. Yet they had assumed that by capturing him, they had unerringly dealt a devastating blow to the power of the government. They had thought that the bugle of revolution had been sounded loud and clear.

He had formed the impression that the youths were being guided by a grave error. And, like him, even the youths themselves did not understand what the outcome of that error would be.

He had not understood, either, whether the ideas in his mind were logical, or erroneous. But his mistrust of the youths had grown. This mistrust had also a simple. reason behind it. His guards had been changed almost every week. By the time he came to know one group of youths who guarded him, they were changed. There was no conversation between him and them.

Only sometimes, when one or two of them who appeared to be some kind of leaders had come, only then had he the opportunity to talk. Looking at the unemotional faces of his guards, he had been unable to fathom their thoughts. He had been unable to trust them. Just as they assumed him to be the symbol of the government, he, too, had thought of each one of them as a diminutive symbol of terrorism.

But four months ago, everything had changed. The change had come from the very day that this youth had taken charge. Even within their own positive magnetic fields, they had discovered small negative charges. This had allowed their two minds to meet.

He did not know whether or not the youth was part of the higher echelons of power. But it was apparent that the youth was not just an ordinary guard. For, on many occasions, he took independent decisions without waiting for orders from above. The youth’s pronunciation of English words had given him the impression that he was highly educated. Though tribal, he spoke Assamese fluently. They talked mostly of everyday matters. Sometimes, however, each of them expressed their opinions and talked of their ideals. The youth professed. deep faith in their revolution, but would listen attentively to what he had to say. There wa disregard in his words. never any callousness or

On the very first day that the youth had taken charge, he had made an arrangement that had changed the very nature of his captivity. Till then, the door had always been locked from outside after he had been put into a room. When the guards were nearby, they had trained their guns at him. The youth had had no gun in his hands on the first day when he had come to him. He had not brought along other guards, either. He had enquired into his wellbeing, and had also given him news of his family. As he was leaving, he had said, ‘Latch the door from inside. I shall be outside. Don’t be afraid. He had gently shut the door behind him.

‘Don’t be afraid.’ These words had a strange effect on him. The emptiness, the sense of discord that he had felt all these days, vanished in a moment. Because the words ‘Don’t be afraid’ followed them, the meaning of the sentence ‘I shall be outside,’ too, had seemed to change. The difference between the two sentences, ‘Don’t try to escape’ and ‘Don’t be afraid’ represented two completely different ways of viewing the same situation.

However, the other circumstances remained unchanged. He had to be shifted frequently from one place to another. They had moved from village to village at night, stung by mosquitoes and bugs. There was no question of staying anywhere for any length of time. For the organization believed in always being in a state of extreme alertness.

The change was in his own mental condition. He was a hostage, the youth was his keeper. Yet, somehow, without their being aware of it, this relationship had now changed. In spite of the difference in their ages, there developed between them a bond of companionship. The youth had never behaved like a guard. Certainly, he always carried a gun in his bag. No doubt, the gun was the sign of their relationship, but that sign had undergone a basic change.

From a sign of terror, it had become a sign of trust.

And so while wandering on their journeys from village to village, through hills and valleys, sometimes he was the youth’s teacher, while the youth was his disciple. Every now and again, the youth would mention some famous writer. At these times, the fact that he was very well-read had been a great help. He had been happy to be able to talk about those writers and their work.

The youth then listened to him like an attentive student. But when the subjects were those relating to nature, rural life, agriculture, farming, and so on, the youth became the teacher, and he the student. He had no clear idea about the relationship between man and nature. In a strange way, this life of captivity helped him to augment the store of knowledge that he had had in his state of freedom.

After reaching a village, on one occasion, he had fallen seriously ill. The high fever made him pass out several times. Even in his semi-conscious state, he had been aware that the youth had secretly gone and fetched a doctor from a distant city. On becoming conscious, he had seen the youth sitting beside his bed. On his face there had been an expression of great anxiety. When the fever had finally subsided, he had come to know from the head of that household that the youth had not stirred from his side until he came round. The youth had given him his medicines, heated water for him; sponged down his body, put cold compresses on his forehead, and had even cleaned up his excrement, all in an astonishingly caring way. However, the youth had not expressed any emotion after he had recovered. He had merely said, Your family was not informed of your illness. They would have been worried. Hope you don’t mind. He had mumbled his gratitude.