“Log Aurat Ko Fakat Jism SamajhLete Hain, Ruh Bhi Hoti Hain Usmein Yeh Kahaan Sochte Hain?”

– Insaaf Ka Tarazu, 1980

“Ek mard ka sar sirf teen auraton ke saamne jhukta hai. Ek apni ma ke saamne, ek durga ma ke saamne, aur …”

– Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, 1998

In Part 1, I focused on the shifting ideas and contours of the ‘empowered woman’ from the 1930s to the 1960s in mainstream Bollywood films. Part 2 starts where we left off, in the mid 1970s, and traces the morphing of this empowered or ‘new woman’ until just before the 21st century.

Discontent and unrest was brewing from the early 1970s onwards,with a host of civil rights and people’s movements, the rise of labour unions, anti-dowry and anti-rape activism, which would ultimately give way to the Emergency of 1975-77. It led to a new era in the 1970s which was rooted in a deeply suspicious and disillusioned attitude towards the State. Family dramas were replaced by action films. Popular culture came to assume an oppositional stance towards the government, with the rise of Amitabh Bachchan’s famous Vijay (meaning victory), the ‘angry young man’. This new culture began with Zanjeer (1973) and thrived with films like Deewar (1975), Sholay (1975) and Trishul (1978). The new hero of the 1970s was angry, often working-class, and usually, the key event that changed the hero and served as the ‘call to adventure’ (or ‘catalyst for vengeance’) was linked to structural issues and the functioning of the State. In Deewar, Vijay lists the moments when the nation failed him – destitution, starvation, exploitation.

While a sympathetic look is offered at this rebellious, grey character, the vengeful woman was a ‘negative’ role whereas the vengeful hero, whatever illegal action he did, was a hero to all.

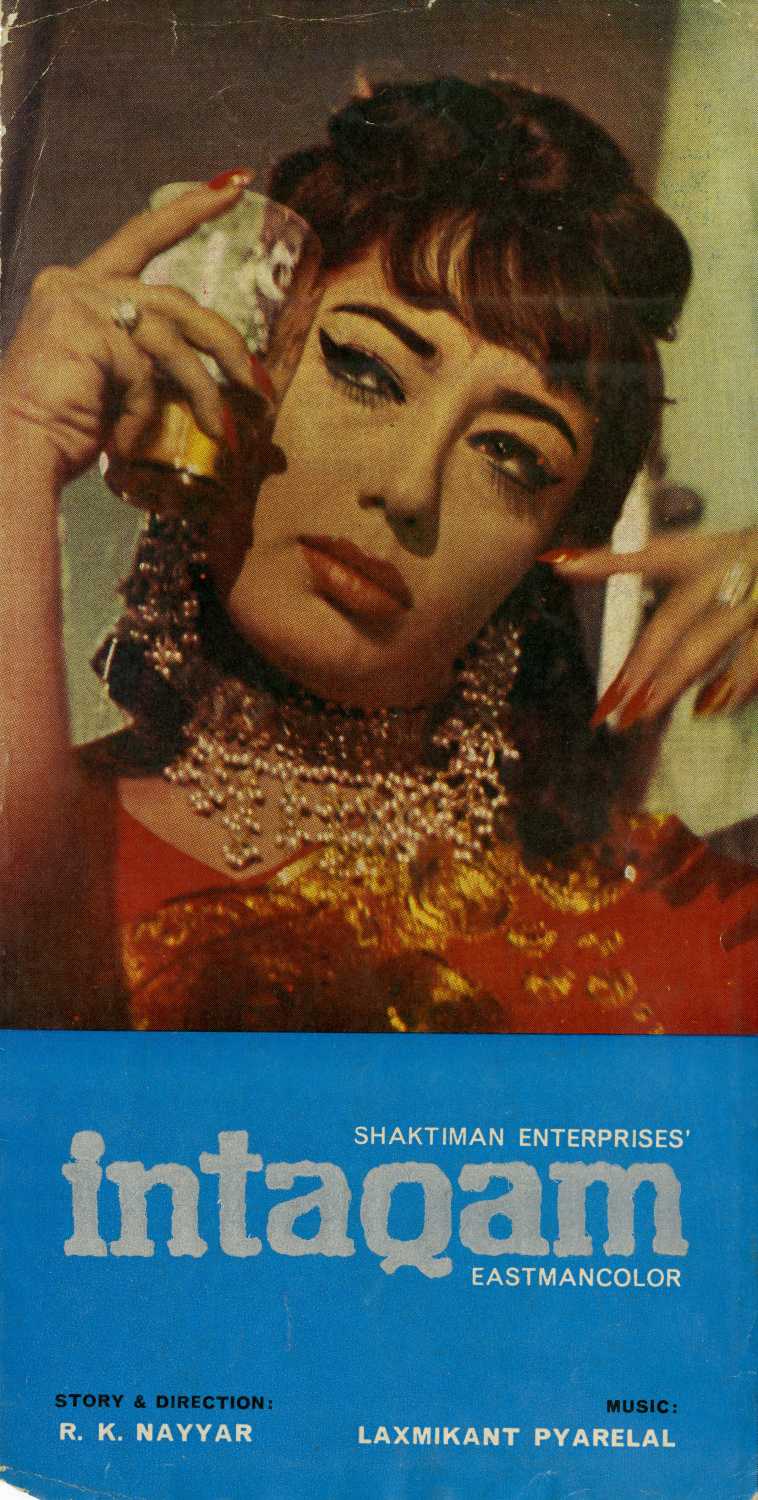

This sentiment of vengeance and anger informed ‘women-centric’ films too. Various revenge-driven films featured women as prominent characters – Intaqam (1969), Lal Patthar (1971), Sunehra Sansar (1975). This anger allowed women in the 1970s to display certain behaviours that were otherwise ‘unwomanly’. Helen’s vamp character gave way to a Westernised heroine, who combined the vamp and the traditional woman. Women could be grey characters, rebel and be angry without being labelled the ‘vamp’. But the ‘anger’ that the woman was allowed to show was markedly different. The woman’s quest for revenge was usually fuelled by a personal or private issue, an isolated incident of hurt or ‘dishonour’, not one embedded within a social structure. Amitabh Bachchan emerged as the working class hero in Kala Patthar (1979), standing not just for himself but for the disenfranchised class. But in Lal Patthar, Hema Malini’s victory was only hers. She played the role of a village widow Saudamani, who becomes the mistress of Kumar, who tries to reform and domesticate her (even changing her name to Madhuri). When he is unable to, he marries Sumita. Saudamani, hurt and enraged, plots to convince Kumar that Sumita is unfaithful to him. He ends up shooting her and then losing his mind. To atone for her wrongs, Saudamani spends the rest of her life tending to Kumar’s hallucinations. Hema Malini later said that she believes she would have won an award for Lal Patthar had it not been a ‘negative role’. Thus, while a sympathetic look is offered at this rebellious, grey character, the vengeful woman was a ‘negative’ role whereas the vengeful hero, whatever illegal action he did, was a hero to all.

The women’s movement of the 1970s was particularly fortified by the Mathura rape case of 1972, when a lower court ruled against the 16 year old Mathura for being ‘of loose morals’ and ruled it a consensual act. Women began to mobilise to fight against domestic violence, dowry, rape and sati. It was only in the 1980s, nearly a decade after it started, that mainstream Hindi cinema started to respond to various issues raised by the women’s movement . Also contributing to this was the ‘new wave’ films that tried to avoid formulae and melodrama, and questioned the status quo. Various actors like Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil and Deepti Naval started to work both in mainstream and parallel films, such as Umrao Jaan and Mandi – (a continuation of the courtesan films mentioned in Part 1). The project of these films impacted mainstream Bollywood’s treatment of women in its stories, and gave rise to a new formula. Firoze Rangoonwala calls the 1980s the ‘age of violence’, as mainstream Bollywood begins to capture ‘the crisis of legitimacy of the Indian State’ (Lalita Gopalan, pp42), a crisis that became even more evident after the Emergency.

A new formula for women-centric films was introduced that combined all these developments, which Lalita Gopalan has named the ‘avenging woman’ genre. But this is a different kind of avenging woman compared to the 1970s. Intaqam (Revenge) of the 1970s gave way to Insaaf ka Tarazu (Scales of Justice, 1980), changing the focus from smaller, personal revenge to a wider sense of justice linked to larger social evils. Central to the narrative for these films was rape or sexual violence, which acted as the catalyst for revenge.

Lalitha Gopalan describes how a typical ‘avenging woman’ plot would play out:

“Films open with family settings which appear ‘happy’ and ‘normal’ … but with a difference: there is a marked absence of dominant paternal figures. The female protagonist is always a working woman with a strong presence on screen. These initial conditions are upset when the female protagonist is raped. The raped woman files charges against the perpetrator, who is easily identifiable. Court rooms play a significant role in these films, if only to demonstrate the State’s inability to convict the rapist and to precipitate a narrative crisis. This miscarriage of justice constitutes a turning point in the film – allowing for the passage of the protagonist from a sexual and judicial victim to an avenging woman.” (Lalitha Gopalan, pp 44)

This genre involved a constant play between violence, revenge and rape. One of the first films within this genre was Insaaf Ka Tarazu (1980), about Bharati (Zeenat Aman) who works as a model, and supports her sister, Nita. Bharati is raped by Ramesh, an industrialist. Although she presses charges against him, she loses. Later, Nita too is raped by Ramesh. Bharati is enraged and kills Ramesh. A criminal trial follows, where Bharati addresses the court on the inadequacy of the legal system, and finally the judge frees Bharati. In her address, however, Bharati refers to Indian women as ‘temples of worship’, whose honour has been outraged. It is this that moves the judge enough to free her. Another classic in this genre is Pratighat (1987), where a local corrupt hooligan ‘Kali’ rapes Lakshmi because she challenges him. She then plots her revenge against him. Here, rape is seen as a ‘social evil’ along with hooliganism and corruption. An individual tale of revenge thus becomes a tale of societal justice, although in a different way from Bachchan’s ‘angry young man’.

These films directed their understanding of women’s issues only to sexual violence, looking at the empowered woman first as a victim and then as an avenger, ignoring her other facets as a worker, a friend, and even the solidarities she forms.

Beginning with the 1980s, directors pushed for overt presentations of both violence and sexuality on screen. The giddy concoction of violence was crucial to the ‘avenging woman’ films, and rape was often used as a device to propel this violence. An obsession with most films within this genre was that of ‘matching rape with revenge’. (Lalita Gopalan, pp?) In Zakhmi Aurat (1988), the protagonist, a policewoman, tallies five rapes to fifteen castrations. Prominent actresses who played this role, like Sri Devi, Zeenat Aman, Dimple Kapadia, believed that such films were welcome portrayals of women as powerful and strong, no longer needing to be submissive or docile. But the narratives of this film need a closer look. These films directed their understanding of women’s issues only to sexual violence, looking at the empowered woman first as a victim and then as an avenger, ignoring her other facets as a worker, a friend, and even the solidarities she forms. These films thus stopped short of drawing their portrayal of women’s issues to ‘its final conclusion: equality’. (Shamita Dasgupta, pp 180)

The liberalisation and globalisation policies that the Narsimha Rao government brought in the 1990s, after four decades of Nehru’s ‘mixed economy’, had a significant impact on mainstream Bollywood films – both directly on the way the industry was organised, and also by providing new symbols, anxieties and desires to film narrative. The changes to the organisation of the industry included a corporatisation of film production in Mumbai, grand productions, a worldwide distribution network, and new media ecology.

The ‘Shining India’ project brought with it a fetishist obsession with speed, shine and commodities. The poor were slowly removed as subjects of films and the urban upper middle class emerged as protagonists. The term “Bollywood” (mimicking “Hollywood”) took a stronghold in the 1990s. This “Bollywoodisation” was the Hindi cinema industry’s reaction to the ‘neoliberal culture industry and its concomitant urbanisation, diasporisation, and globalisation’. The NRI emerged as an important figure, and many films were targeted towards the diasporic audience, since monetary NRI investments were transformed into a particular kind of emotional nationalism targeted at them.

But all these changes also brought with them a sense of loss.The relationship to the West included simultaneously seeing it as an ‘emblem of modernisation’ and a ‘parasite on Indian tradition’. Bollywood responded to these anxieties by, on the one hand, showcasing Western phenomena such as Valentine’s Day, and on the other hand, repackaging and bringing back into fashion, parochial and regressive Indian traditions like Karva Chauth.

The anxieties that liberalisation brought coalesced around the ‘new liberal Indian woman’. On the one hand, she participated in commodity consumption, was professional and urban. On the other hand, all the anxieties around loss of a ‘national culture’ were displaced onto this woman’s body. Anxieties about the nation were morphed into anxieties about the indiscretions and degeneration of the ‘new woman’. Her role as a consumer was carefully dissected – she should be rooted and wedded to her values and her heart must be within the family, rather than easily seduced by shiny new objects. She was constantly scrutinised: she could be a ‘new woman’, but not ‘too new a woman’.

Films like Hum Aapke Hain Koun…! (HAHK), Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ, 1995) and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (KKHH) are all stories of idealised Indian families. HAHK in particular, marks a watershed moment for family dramas in the 1990s. Within this family, the foremost characteristic of the ‘new woman’ is her ‘hybridity’. She is often both Western and Indian, and often located geographically in the West, like in KKHH, where Tina has come back from studying at Oxford University, or Simran from DDLJ, whose one desire is to go on a girls’ trip to Europe. She is no longer confined to her home, but her most important quality is that she has seen the outside world, and still chooses to stay rooted in Indian tradition, which she believes is superior to all. Tina can sing the Gayatri Mantra and often visits a temple, which is when Rahul realises he loves her.

She is no longer confined to her home, but her most important quality is that she has seen the outside world, and still chooses to stay rooted in Indian tradition, which she believes is superior to all.

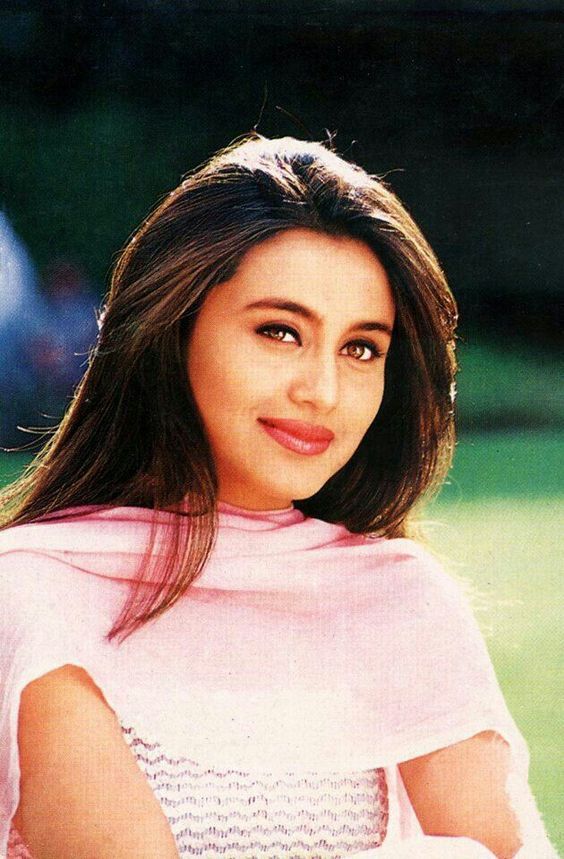

If this woman isn’t yet in touch with her roots, it means she is still a girl, not a woman. Love will eventually transform her. The good woman-bad woman binary gets subsumed within one woman’s character arc. So Anjali in KKHH becomes marriable for Rahul the moment he sees her with long hair and a saree. And the Westernised Simran who attends parties and listens to pop music, upon shifting to Punjab for marriage, starts dressing in salwars and practicing Karva Chauth. HAHK was full of product placements, shiny objects, and display of wealth, from shoes to computers to candy bars. But a big part of the plot is centred around scrutinising what the female lead (the ‘new woman’) does around these products. Nisha (Madhuri Dixit) is a loud, unapologetic girl who loves her ‘chocolate, lime juice, ice cream, toffiyan’ and has huge portraits of herself on her wall. When she finally realises her love for Prem, the two end up in Nisha’s bedroom, right below the giant self-portraits and photos of her indulgences. ‘The collapsed bed, then, not only connotes ignited erotic desire but also the need to find a new avenue for its fulfilment’, as Nisha gives up her ‘childish indulgences in favor of adult obligations.’ (Anwer, pp 302) The hit song from the film now holds a new meaning: “Chocolate, lime juice, ice cream, toffiyan, Pehle jaise abb mere shauk hain kaha; Gudiya khilone meri saheliya, ab mujhe lagti hain saree paheliyan; Yeh kaunsa mod hai umrr kaa…”

We can compare Nisha’s character to that of Bhagwanti, an older woman (maami) in the family, who acts as a sort of cautionary tale. Despite being much older, she still is seduced by Western values – kitty parties and salons, sleeveless blouses and short hair. When her niece Rita mistakenly cooks halwa with salt instead of sugar, everyone else is horrified, but Bhagwanti continues to eat and eat, as the camera closes up on her facial expressions. She is the woman who never learnt, and was never reformed into domesticity, a symbol of uncontrolled consumerism. Much like the older teacher from KKHH, Ms. Breganza, a promiscuous westernised woman, who is both a desirable object and the butt of all jokes.

In mainstream Bollywood films between 1997 and 1999, 40 percent of the sexual scenes also included violent acts.

In films like Darr (1993) and Daraar (1996), one saw other ways of taming this ‘new woman’ — stalking, ‘eve-teasing’, and control. The link between sex and violence established in the 1980s continued through the 1990s. Ramasubramanian and Oliver (2003) showed that in mainstream Bollywood films between 1997 and 1999, 40 percent of the sexual scenes also included violent acts.

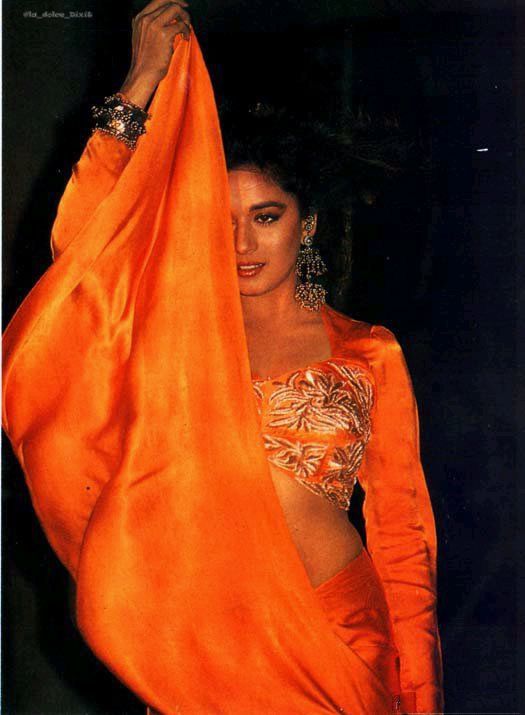

The dichotomy between vamp and heroine disappeared even more. Madhuri Dixit could dance raunchily to ‘Dhak Dhak Karne Laga’ and ‘Choli KePeechhey Kya Hai’ without being labelled the vamp. The ‘new woman’ emerges as a hybrid of sorts. She is not just Indian and Western, good and bad, she is also a combination of recurring tropes –‘a superwoman, imagined as a hybrid figure who amalgamates in herself the sacrifice and resilience of a mother; the dutifulness of a wife; the assertiveness, aggression, and righteous anger of the avenging woman; and the sensuality and sexual allure of a courtesan’. (Anwer, pp9) She is an all-in-one package, emblematic of her times!

Sridevi ruled the roost in the late 1980s. She defeated villains on her own and stole the screen, so much that she was often touted as a ‘hero’. But her image was a polysemic one – she could be both tragic and comic, innocent and mature, fun and serious, sensuous and sweet. This multifaceted and contradictory image helped her transition smoothly from the avenging woman of the 1980s to the “new woman” of “old” India in the 1990s. She walked the tight rope between tradition and modernity. Her career trajectory helps us to map the changing ideas of the empowered woman in mainstream Bollywood.

The family dramas of the 1990s involve a notable absence of a traditional villain, of violence and of politics. The progress made in the 1980s, the anger towards the State or towards injustice (however skin deep it may be) was left behind in the quest to abate newer anxieties about loss of national culture. There was a new obsession with happiness, and the site of happiness was always one’s family, that reminded you of your roots. Films of the 1990s became relatively ‘pain-free’ (Bhattacharya, 2008), as they advertised a new era.

The ‘new woman’ now had to smile harder to paper over all the cracks, as she became the contested borderland of negotiation between tradition and modernity. In 2001, as the government officially recognised the industry, and as multinational companies like Sony began to flood the market in 2005, the ‘new woman’ would further morph, to assuage new fears and sell new dreams.