Prime Minister Narendra Modi is at it again. He has mastered the art of manufacturing controversy. His goal is a simple one. Fan Hindutva passions at regular intervals so that people stay distracted and do not start asking uncomfortable questions about rising prices, runaway unemployment, or the country’s foreign policy reverses. Even larger concerns relating to centre-state relations or citizens’ right to privacy in the face of Pegasus spyware threats get marginalised.

The latest on Modi’s display board is his decision to declare the 14th day of every August (15 August is India’s Independence Day) as Partition Horrors Remembrance Day. Remember that 14 August is Pakistan’s Independence Day. It is hardly desirable for two neighbours to mourn and celebrate on the same day. Speaking from a narrow diplomatic perspective, it ensures that India cannot even send a congratulatory message to Pakistan on that day. Pakistan may be India’s enemy number one today, but it is not impossible that someday their relations will normalise, a common enough happening in international relations.

Delivering his Independence Day speech from the ramparts of Delhi’s historic Red Fort, Prime Minister Modi declared: “My dear countrymen, while we celebrate our freedom today, we cannot forget the pain of Partition that still pierces through the heart of all Indians. This has been one of the biggest tragedies of the last century. After attaining freedom, these people were forgotten too soon. Just yesterday India has taken an emotional decision in their memory. We will henceforth commemorate 14 August as Partition Horrors Remembrance Day in the memory of all the victims of Partition. Those who were subjected to inhuman circumstances, suffered torturous treatment, they could not even receive a dignified cremation. They must all remain alive and never get erased from our memories. The decision of celebrating Partition Horrors Remembrance Day on the 75th Independence Day is a befitting tribute from every Indian to them.”

It is rather surprising that the 80-minute speech, otherwise so full of positive news about high-profile government programmes and the promise to lift every Indian regardless of caste or creed (sabka saath, sabka vishwas, sabka prayas), should have included such a divisive element. After all, he boasted that the nation was on the threshold of a 25-year period of glory (Amrit Kaal).

There is little dispute over the fact that Partition victims and their families deserve sympathy and support from every Indian. But the problem is that Modi was clearly seeking sympathy only for Hindu and Sikh victims of Partition, as if Muslims did not suffer at all. If you are unconvinced, try reading his remarks again: “Those who were subjected to inhuman circumstances, suffered torturous treatment, they could not even receive a dignified cremation (emphasis added).” Now recall his speeches during the 2017 Uttar Pradesh Assembly election. In them, he pointedly castigated the previous Samajwadi Party-led Uttar Pradesh government for neglecting the maintenance of Hindu cremation grounds (shamshan) while lavishing attention on Muslim burial grounds (kabristan). There were other instances too, when Modi sent the same message in a bid to energise Hindu votes at the cost of India’s Muslims. One has ample reasons, therefore, to smell a rat in Modi’s latest proclamation.

What Modi said was soon buttressed by his party colleagues. Vijay Chauthaiwale, the in-charge of BJP’s Foreign Affairs Department, went on to dissemble: “Imagine a situation: In a joint family, a baby is born and on the same day, the eldest and most respected person in the family is brutally murdered. While everyone will celebrate the arrival of the newborn… will anyone argue that in this celebration, everyone should simply forget the murder—not even mourn, forget about wiping the tears, of close ones in the family?” Mark his use of “eldest” and “most respected person”. Here he clearly meant to connote Hindus.

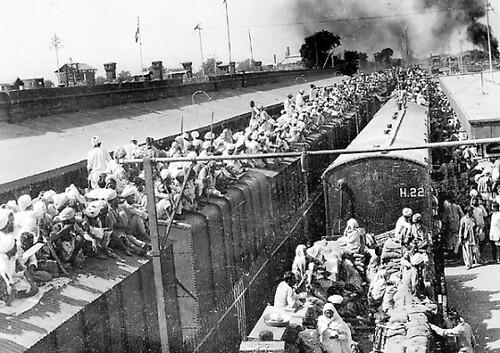

Moreover, who is preventing anyone from mourning or wiping the tears? Volumes upon volumes of research on Partition (including oral histories) demonstrate how much of a tragedy it was for Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs alike. To the best of my knowledge, although there is no clear community-wise break-up, we do know that the casualty figures were in the millions. Varying across specific locations and circumstances, the physical and psychological suffering was comparable for all communities.

Recently, after the fortnightly column of one of India’s noted interviewers and commentators, Karan Thapar, was published in the Asian Age on the anti-Muslim riots in Jammu in 1947, the paper’s management felt uncomfortable and kept his future columns on hold. Probably that is the end of his column. Thapar’s ‘crime’ was to write about the massacre of Jammu’s Muslims during October and November 1947. The editors would do well to note that preventing a column from appearing in print does not gloss over the facts of the matter: a large number of Muslims were indeed killed in Jammu. Have we not read how the anti-Hindu pogrom in Noakhali (East Bengal, now Bangladesh) was avenged in Tarapur (Bihar) and Garh Mukteshwar (Uttar Pradesh) resulting in huge Muslim casualties?

Memory science is a serious academic vocation. It should not be reduced to petty political ping pong. Given the paucity of space, let me make just two quick points. One, on how Jawaharlal Nehru dealt with Partition memory given his commitment to an inclusive nation-building and development. Two, on why reconciliation with a tragedy is not only essential but also requires constant human effort, as the Holocaust and other experiences suggest.

It is politically fashionable these days to obliterate Nehru from the pages of history. Nehru baiters believe that if children are not allowed to read about the man, then fifty years from now all Indians will accept that independent India’s history begins on 27 May 1964, the day of his death. BJP’s penchant to belittle Nehru sometimes plumbs the depths of pettiness. Recently, the government-controlled (though technically autonomous) Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR) released a poster to mark the 75th Anniversary of India’s independence. The poster displayed pictures of Mahatma Gandhi, B.R. Ambedkar, Sardar Patel, Subhash Chandra Bose, Rajendra Prasad, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Bhagat Singh and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (the father of the Hindutva ideology). Nehru’s image was conspicuously absent.

As with any historical figure, one may critique many aspects of Nehru’s policies. But this wild-eyed and desperate effort to obliterate his memory is neither good politics nor good history. The fact remains that on the question of dealing with the trauma of Partition, including the rehabilitation of millions of refugees from West Punjab, Nehru’s contributions are remarkable. Moreover, he also knew how important it was not to let that trauma derail India’s development goals and nation-building priorities.

During his 17 years as prime minister, the state-run Films Division of India produced about 1,700 documentaries with the sole purpose of educating viewers about the various national development projects underway. These films were full of stories about new bridges, dams, electricity plants, and engineering colleges, and about the creation of vital public services. References to Partition violence were altogether avoided. (Even Bollywood played its part. Recall the 1960 song chhodo kal ki baatein; set aside the past). But it did touch upon the theme of Muslim culture and its crisis of existence, another subject that the Films Division documentaries avoided.

Turning to our second point, on the importance of reconciling with a mass tragedy, it is helpful to consult Martha Minow, an authority on the subject. In her book, Between Vengeance and Forgiveness (1998), she writes, “To seek a path between vengeance and forgiveness is also to seek a route between too much memory and too much forgetting. Too much memory is a disease.” In similar vein, another author from the same field writes, “How do we keep the past alive without becoming its prisoner? How do we forget it without risking its repetition in the future?”

Some practical efforts are worth recalling here. Starting in 1992, Mona Weissmark, whose parents survived Nazi concentration camps, and Ilona Kuphal, whose father served as a Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel, a high-profile paramilitary outfit) officer, organised a series of get-togethers of children of Holocaust survivors and Nazis. Their goal was to rebuild the future through explorations of intergenerational memories and emotions of guilt, anger and resentment. Nelson Mandela’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is another instance of this idea put into practice. The meeting between Priyanka Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi’s daughter, and Nalini Sriharan, Rajiv’s killer, on 15 April 2008 in Vellore Jail is yet another example of reconciling with a difficult memory. “It was my way of coming to peace with the violence and loss that I have experienced,” Priyanka said after the encounter.

Postscript: Against the background of Hindu-Muslim trauma caused by Partition, Bollywood was remarkably on board with the Nehruvian secular ethos of the times. Most Hindi movies produced in the wake of 1947 had a blending of Hindu and Muslim characters. Quite often, Muslim actors played Hindu roles and vice versa. Amar (1954) stands out in this regard. Its song, Insaaf ka mandir hai yeh, bhagwan ka ghar hai; this abode of God has to be the temple of justice, was an all-Muslim affair set in a Hindu temple. Mehboob Khan directed the scene, Dilip Kumar, Madhubala and Nimmi, all Muslims, played the three main Hindu characters, Naushad Ali gave music to Shakeel Badayuni’s lyrics, which were, in turn, sung unforgettably by the one and only Mohammad Rafi.

Despite the best efforts of its enemies, such an ‘idea of India’ still survives. While reporting about the growing Hindu-Muslim polarisation during the West Bengal Assembly election of March-April, The Hindu reporter Shiv Sahay Singh dug through his diary and found the following note: ‘During the Basirhat riots of 2017, 65-year Kartik Ghosh was stabbed. His son, Prabhasish Ghosh, while rushing his father to a hospital in Kolkata, also took Fazlum Islam, another victim, in the same ambulance. While Ghosh died, Islam survived. Similarly, in the Asansol riots of 2018, Maulana Imadullah Rashidi urged people from his community to exercise restraint even after the Imam’s 16-year son was killed in the riots. “I will leave the city if members of the community target the other community,” he said.’