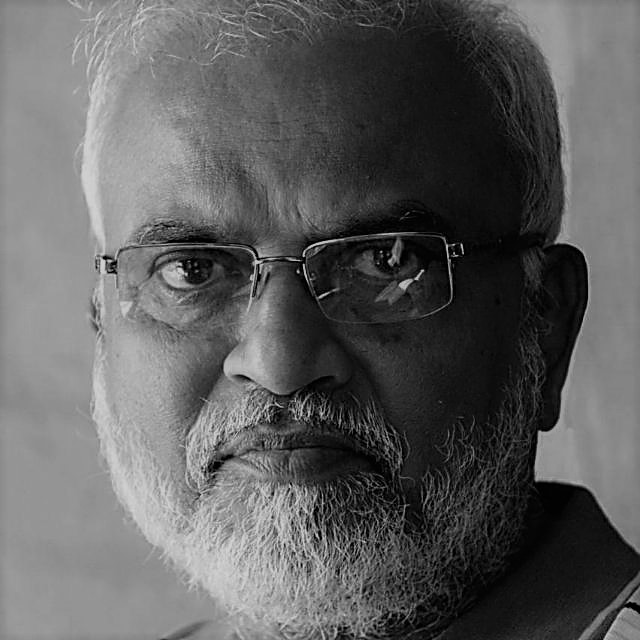

Tributes have poured in for Satish Kalsekar — poet, essayist, bibliophile and a leading figure in the little magazine movement in the 1960s — who passed away last month at the age of 78. Relentless traveler and a fierce critic of inequality, Kalsekar was loved by common people as well as social activists, artists and writers from villages, small towns and cities. It was always a a joy to meet Kalsekar sir, as I would address him. He showed an interest in others’ lives and writings. Making up stories about the books that he read came as naturally for Kalsekar as breathing.

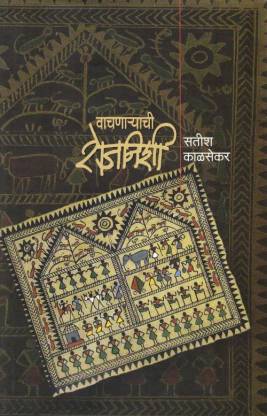

Satish Kalasekar was a part of the anti-establishment, little magazine movement in the 1960s. He took care of fragile little magazines, a valuable asset for our culture, with a mother’s love, stored them or handed them over to responsible archivists. He scrupulously maintained handwritten notes about the books and the writers he loved. He loved people who cared for books. He spent hours skimming through second hand books at the footpaths in Mumbai or any other place across India. I read an anecdote about how he was emotional when someone didn’t return the books he lent. He wrote a number of candid pieces in his column ‘Vachnaryachi Rojnishi’ (Diary of a Reader) for the Vangmaya Vrutta and the Saptahik Sadhana talking about his readings that were published later in a book of the same title and received the Sahitya Akademi award in 2013. His writing about books isn’t pacey. Instead, he took delight in telling stories about the books he read in Marathi, Hindi or English in a lucid style. His readers felt that he spoke directly to them. Whenever I met him or shared my work with him, I was struck by his readiness to talk, to support and to encourage. He was friendly and cordial even when he was revered as a pioneering figure in the little magazine movement along with his contemporaries like Dilip Chitre, Namdeo Dhasal, Raja Dhale and several others.

The sixties were an important decade for not just Maharashtra but the whole world. The issues of Maharashtra and alternatively the Marathi language, culture, history, politics, society and economic system were discussed, debated and reflected upon in the 60s. In the same period, a strong stream of dalit literature–of rural, tribal, rebel and different voices of the dissent–showed a new way ahead. It was the era that questioned the mainstream.

Kalsekar didn’t move away from the anti-establishment to settle down in the mainstream. With his base in the small town of Pen in the Raigad district of Kokan, Kalsekar remained actively involved with various literary activities across Maharashtra. He was associated with Lokvangmay Griha and People’s Book House in Mumbai–places that became a halt for many to exchange books and ideas. He was also closely connected to the great work done for the common people by Comrade Govind Pansare. Wherever Kalsekar went, he carried books, read poetry, shared his views and inspired young minds. Until his next visit to the same places and people, he stayed connected through beautifully written postcards and phone calls. One would never feel left out with Kalsekar.

Kalsekar’s poetry, the direction of thoughts and its future were greatly influenced by Marx, the long surviving Marathi literary traditions and the little magazine movement. He was a part of the generation of writers– Kolatkar, Chitre, Dhasal, and Dahake among others–that succeeded in discovering the roots of their tradition deep into Mahanubhav and Sant poetry of medieval times. Their poetry offered a unique experience of complexities and intricacies of life and linguistic capabilities. Noted for the rootedness, linguistic integrity, compassion and portrayal of consequences of oppressive forms in the society, Kalsekar’s poetry, like his contemporaries, encapsulated the reality of the time.

Kalsekar’s writing revealed his inner need to share knowledge. As he writes in his poem ‘Still There is Much More Left’, he had an urge “To Tell, To tell/And, empty yourself”. However, it’s not only for his own self but also for his bhavtaal or the milieu that Kalsekar wrote about in his selective and valuable works of poetry. He has three collections to his credit: Indriyopnishad (1971), Sakshat (1982) and Vilambit (1997).

His poetry celebrates love between a man and a woman with a great intensity of emotions. There is an appeal of lovers towards the existence of each other. His poems give newer dimensions to the existence of human beings living and growing on the cusp of the rise and the convergence, the beginning and the end. He writes,

Beginning, end and beginning

Such is the ongoing war

A thing to be done

With you by my side

In the later phase of his writing, Kalsekar went beyond the physical expression of love to take “a spiritual leap”. He writes, “It was a sign that the stage of understanding a woman through the body was over. There has been the inevitable importance of the body in the male-female relationship that I had previously emphasised strongly. It’s not over for me. But I don’t think a woman’s body is enough to take her to the next level of understanding.”

Kalsekar’s poetry doesn’t stop by celebrating the senses, but builds the network of emotions through the bonds between individuals. The bonds are not only attracted to each other to seek love but also embedded in complicated social systems and hierarchies. The introverts in his poems reflect upon the milieu within their personal spaces.

Kalsekar was very clear about what literature meant to him or why he wrote. In his poetry as well as prose, he doesn’t see personal and social life distinct from each other. They are intertwined and come together through the combination of both. The passionate urge in his poetry has been transformed into compassionate human feelings. While his poetry is about loss and life approaching its natural ending, his words fly with prayers to give voice to the silent and the voiceless.

Inspired by the sant sahitya of medieval times and by Keshvsut and B C Mardhekar in modern times–like many of his contemporaries from the little magazine movement–Kalsekar broke the rules of poetry as a reaction to stereotyped linguistic allusions. However, as he also made clear, the rule-breaking experiment was not his priority, it was being faithful to the content of the expression. For him, being rhythmic and lyrical in poetry was not enough for a poem to be good. It had to also be genuine and loyal to the depth of our experiences.

Inspired by Marx’s ideology of changing the world, Kalsekar went beyond expressing at a personal level. He never stopped from believing in a better world and didn’t shy away from fighting for it in his own ways. Active in the employers’ unions in the bank he worked with, Kalsekar believed that a writer should face the troubling questions of his time in order to change the society for the better.

While talking, I, like many others, would see Kalsekar’s eyes glittering with dreams–for a better human life–that gave meaning to his life and creativity. He let others see dreams not only for the present but also for the future. His death has left a massive hole in our lives and our world–of words, of books and of actions. Writers and readers like me who may have received warmly written words of love and trust from him, on a postcard or a book, would dearly miss him. His words will encourage us to dream–undeterred and firm.