On a train that left Arsikere in the princely state of Mysore, two men in their early twenties were on their way to Bangalore, and an uncertain future. It was 1943, a tumultuous year. The Second World War was raging, and British colonialists had harshly suppressed the nationalist Quit India movement. Bengal was faced with famine.

D. Shankar Singh had just sold his small businesses, two touring talkies that rented and screened movies, named after M.K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. His companion, B. Vittalacharya, had sold his small restaurant. With the spoils, they were on their way to buy a bigger prize, the film company Prabhath Talkies. Mahatma Touring Talkies and Jawahar Touring Talkies used to make Shankar about ₹300 per film in collections, a not unhealthy sum for those times. But the duo didn’t just want to exhibit films. They wanted to make them. Over many dosai and coffees in Vittalacharya’s restaurant, they’d decided to risk it, and purchase a studio in the big town.

The train ride proved life-changing for them, in an unexpected way. En route, they met filmmaker C.V. Raju, then a rookie desperately looking for funds to make a film. He managed to convince Shankar and Vittal “not to sink money into a studio,” but come and produce Krishnaleela, which he had already started shooting. He succeeded: Shankar and Vittal bought the film’s distribution rights for ₹75,000.

In all the excitement, however, the freshly minted producers had failed to notice one crucial detail. In a shrewd performance that outdid the troupe of hapless theatre artistes he had hired for a pittance, Raju had been shooting with a camera but no film. It was wartime; film was strictly rationed and prohibitively expensive. Raju was faking the shooting to demonstrate that he was hard at work.

This was not even his only deception. Shankar and Vittal were also persuaded to make several bottles of whiskey liberally available to the team. They were told that it was important for new “film developing techniques.” They learnt of the charades only weeks later, after a tip-off by a technician. There was a massive confrontation, after which Shankar and Vittal took over the shooting.[1]

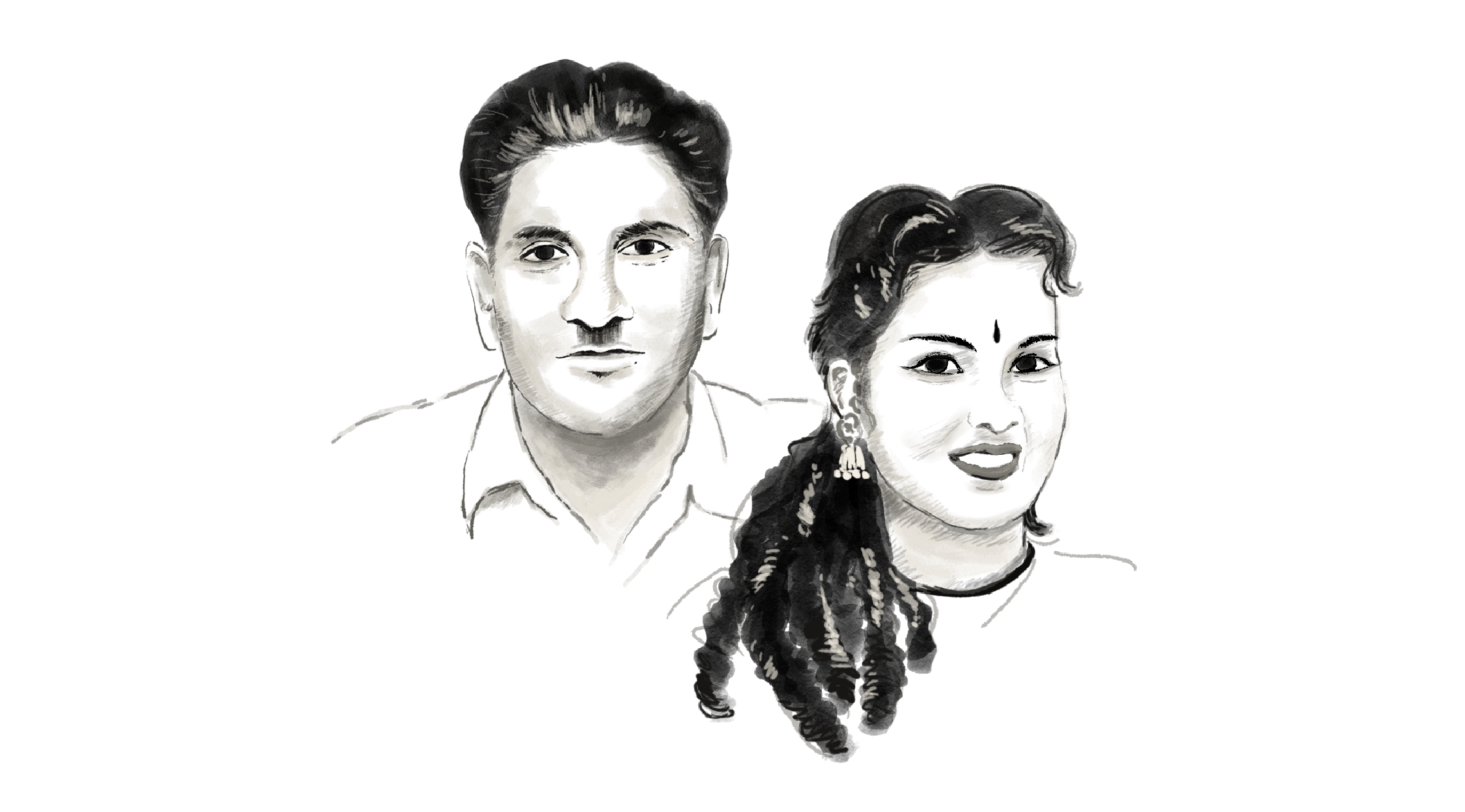

That was how D. Shankar Singh became a director-producer. Krishnaleela, released in 1947, was the first venture of the newly formed Mahatma Pictures. The film tanked at the box office, but it was the beginning of a crucial chapter in the history of popular Kannada cinema. It was also the start of the studio career of a man of many parts: freedom fighter; Brooke Bond tea agent; touring talkies owner, and cinema pioneer.

[…]

Shankar Singh infused life into Kannada cinema in a period when it had nothing going for it. He insisted that his projects were shot within the state, convincing his peers to think beyond Madras, the big southern film centre of the time. His films, in which the story was the “hero,” were about a wide range of subjects: mythology; the caste system; Lingayat philosophy and unscrupulous charlatans. His work didn’t shy from showcasing sensuality and female desire. Jaganmohini, his greatest hit, had a woman boldly trying to win over the man as a second heroine, and not as an out-and-out vamp. (Jaganmohini also dazzled audiences by deploying the latest special effects technology for its time.)

Outside Karnataka, Kannada cinema remains less storied than its counterparts in Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam. The global Kannadiga diaspora isn’t as large as that of the other southern states, nor is it as enthusiastic about watching Kannada films.[2] Tamil and Telugu cinema are widely and lovingly chronicled in popular histories in their own as well as other languages. Many blanks remain in the story of the early days of Kannada cinema. This story, about an early pioneer whose birth centenary falls on Independence Day this year, attempts to fill a few of those.

[…]

Over the late 1940s and early 1950s, Tamil cinema was already challenging the dominant social order. The Hindi movie industry, rocked by Partition, was committing itself to Nehruvian visions of modernity and freedom. The Kannada audience, in contrast, appeared not to be in the mood for such interventions, and early filmmakers focused their attention on an ever-popular category, folklore and mythology.

Shortly after Krishnaleela, Shankar and Vittal made Bhakta Ramadas, a film about the seventeenth century composer of Carnatic music. After it flopped, the general advice to the young men was to pack their bags and return to Arsikere. They stood their ground. Their next experiment with folklore, in 1949, was Nagakannika. The lead character, played by Jayashree, would morph into a snake on a full moon day: a transmogrification depicted using techniques that were unusual for their time. Nagakannika became a huge hit, successful enough to be dubbed into Tamil and Telugu.

The Kannada film industry was now 15 years old. Sati Sulochana, the first Kannada movie in recorded history, was made in 1934. But it had produced fewer than 30 films. The Hindi, Tamil and Telugu industries were already established, and had a head start on technology. In Mysore state, cinema was still centred around Bangalore, and smaller towns were still in transition from the travelling talkies to the cinema hall.

Navajyothi Studios became a landmark accomplishment. Even Tamil stars came to work there. Most memorably, a certain M.G. Ramachandran, shot a film called Maruthanad Elavarasee there in 1950, with his co-star, V.N. Janaki. There was a huge upheaval in Mysore when it came to be known that MGR and Janaki were in love. Janaki was married at the time, with a son, and Ganapathi Bhat, her make-up artist husband, threatened to register a case of abduction against MGR. The fracas only ended when one of MGR’s local friends stepped in. That friend was Shankar Singh. (MGR and Janaki finally married in 1963, and I was told that MGR never forgot Shankar Singh’s favour.)

In 1951, Mahatma Pictures’ Jaganmohini created a record when it became the first Kannada film to run for 100 days. The plot involved a reborn woman returning to woo her much-married man back. The film’s talking point was its 14-year-old actress Harini, originally from Udupi and already a popular theatre artist in Madras. It became a sensation in towns like Davangere and Bijapur, not least because it featured scenes in which Harini variously wore a wet, white sari and a bikini.

There were reports of farmers selling their cattle to be able to watch the film multiple times. After the film was screened for 25 weeks straight, an agitated District Commissioner in Davangere cancelled the licence of the hall. “It took Shankar Singh’s determination and good legal support to be able to reverse the decision,” said director S.V. Rajendra Singh, Shankar Singh’s son and former chairman of the film academy in Karnataka. [3]

S. Vijayalakshmi, Shankar Singh’s producer-actor daughter, told me another Jaganmohini anecdote. Since music records used to be released before the film, Mahatma’s team had been able to get hold of the record of Kamal Amrohi’s Mahal. After hearing the “Aayega Aayega” track, they were able to quickly rustle up “Yendo Yendo” for Jaganmohini. Critics were misled into thinking it was Mahal that lifted from the Kannada original. [4]

[…]

Shankar had learned to hold his ground in hard battles. In the mid-1950s, his own comrade Vittalacharya left Mahatma Pictures to produce films in Madras. Shankar, despite repeated entreaties, stubbornly refused to join him. In the Madras studios, Kannada and Malayalam cinema were given second-class treatment. Tamil and Telugu cinema had the first priority for floor space, and Kannada films would often only get the night shift after 10pm.

The Kannada-enthusiast in Shankar Singh refused to countenance this. He lobbied the Karnataka government to make their newly created state the hub of Kannada cinema. In 1962, he prevailed upon the chief minister S. Nijalingappa to provide a subsidy for films made in Karnataka. This was an old connection: the CM was a fellow freedom fighter and Congressman from the Arsikere days. Then finance minister Ramakrishna Hegde agreed to provide a subsidy of ₹50,000 to films shot wholly in the state. (The government levied a surcharge of a rupee per ticket for its film fund.)

Here is where the stories of Karnataka’s popular cinema and its arthouse cinema happily intersected. The subsidy provided a fillip to the Kannada New Wave, which went on to receive critical acclaim around the world. The 1960s and 1970s were a period of frenzied activity for towering Kannada literary figures. There was a kind of renaissance in the world of art, theatre, writing and cinema.

Award-winning writers like Shivarama Karanth, Girish Karnad, P. Lankesh, Baraguru Ramachandrappa and Chandrasekhara Kambar turned their attention to directing films. Theatre personalities such as T.S. Nagabharana started working in cinema, too. Filmmakers like Girish Kasaravalli made their first movies because of these state subsidies.

Government policies, the film writer Jayanth Kodkani explained, “led to the encouragement of independent expression or offbeat themes in cinema. The Film Finance Corporation”—later the NFDC—”was a major boost.”

Popular Kannada cinema started paying attention to literary works in the late 1960s. In Kannada Talkies, K. Puttaswamy argues that this is what set the stage for the new cinema of the 1970s. The popular writer Triveni’s novel was adapted to Beli Moda. Chakrateertha, based on Tha Ra Su’s work, Mallamanna Pavada based on B. Puttaswamaiah’s novel, and Eradu Mukha, adapted from the work of Aryamba Pattabhi, were all produced following this. Films like Aruna Raga, Upasane and Bangrada Manushya were easily more popular than the books they were based on.

In 1970, Pattabhirama Reddy made Samskara, based on the famous novel by U.R. Ananthamurthy. That screenplay was written by Girish Karnad, who also starred in the film. If there was ever a watershed moment in modern Kannada cinema, it was this: Samskara won a National Award for Best Feature Film and inspired a generation of filmmakers to work on literary adaptations.

The Kannada New Wave was steeped in the influence of Italian neo-realism and the French New Wave, as well as Kurosawa’s vibrant sentimental epics. But, Kodkani pointed out, they were also indebted to their political inheritance, what Karnad called “a product of a generation associated with Nehruvian dreams.” In this, the one-time proprietor of Jawahar Touring Talkies had played his part.

1. The film was procured via an agent of the Kodak company in Madras—he was popularly called Kodak Ramamurti.

2. See this interview by S. Shiva Kumar with Satish Shastri, described as the “sole distributor” of Kannada films abroad. Published in The Hindu in January 2019.

3. S.V. Rajendra Singh carried forward his father’s legacy. He bagged a national award for Nagarahole. Antha was a blockbuster, as were films like Muthina Haara and Bandhana. He dabbled in Hindi with Meri Awaz Suno and Sharara. Aag Ka Dariya, shot in 1990 and starring Dilip Kumar and Rekha, may well be his finest film. But it has not yet got a release due to several production issues. Singh is still hopeful that it will be released some day.

4. Mahal released in Bombay in 1949, but made its way to the B and C centres of Karnataka much later. The tune “borrowing” anecdote even finds mention in K. Puttaswamy’s Kannada Talkies, on page 39.

Read the full article here.