Narratives associated with the characters and happenings in the Ramayan epic abound in folk and tribal communities across India. Some bear strong resemblance to the storyline as presented in the Valmiki Ramayan or Tulsi’s Ramcharitmanas, and yet there are others, which depart from them in several ways. It is now commonplace to look at these narratives as alternative tellings of the Ramayan and analyse them from the standpoint of various processes that go into their making such as, localisation, domestication, augmentation etc.1 The import and discourse in these Ramayans is often seen as non-hegemonic or counter hegemonic in relation to the Ramayan. In this essay I attempt to explore one such text, namely the Gond Ramayani that lends itself easily to a reading that makes a case for it to be seen as a “Ramayan in inverse” or “Ramayan inverted”. However, I argue here that such a reading risks overlooking the multilevel meanings and multilayered symbolism with which the Gond Ramayani is replete. Its archetypes are not borrowed from the Ramayan and we need to search for them elsewhere. Despite obvious similarities with the Ramayan storyline, though inverted ones, the Gondi text is not about the Ramayan. It is a text, which encodes the Gond discourse on human body, sexuality, life and death, social and sexual anxieties and has strong philosophical and psychosocial undercurrents running throughout the text. It may be more fruitful to focus our attention on this discourse and search for its archetypes and metaphors within the broader repertoire of Gond narratives, rituals, belief systems and socio-cultural moorings.

One could say that the Gond Ramayani starts from where the well-known Ramayan story almost ends, much after the Ram – Ravan war has ended. In fact the Gond Ramayani doesn’t deal with the Ramayan story at all. Its thematic content is all together different. The Gond Ramayani is composed of seven separate tales that are loosely strung together to form a cycle. Its traditional singers are the Pardhan Gonds from the Mandala and Dhindori District of Madhya Pradesh.2 The Gond Ramayani is known by several names- Ramayani, Lachhman sat pareeksha, Lachhman charit or after the name of an individual tale in the cycle e.g. Lachhman and Tiriyaphool; Lachhman and Inderkamini and so on. The cycle is also known as Tiriyaphool or Machhandar Kaina (daughter of Raja Machhandar)

Lakshman is the main hero of the Gond Ramayani as he is in many other versions of the Ram story among the tribal communities. The Gond narrative, which has more to do with the characters of Lakshman and Sita, remains largely indifferent to the character of Ram. It is only the last tale Sita Banvas in the cycle that has a strong resemblance to popular folk and some textual versions of the episode of Sita’s exile. This tale departs from the other tales in the cycle in its thematic content and appears to be an interpolation. All the other tales are about Lakshman’s quests for various brides at the behest of Sita, and about the obstacles and travails he faces during these quests.

The cycle begins with the story in which Lakshman undergoes a trial by fire to prove his chastity. There are several versions of this tale. In one of the versions of this tale Lakshman disheartened by allegations against him of being untruthful, requests the mother earth to open up and give him refuge. This motif is repeated in several other tales in the cycle where Lakshman in order to escape from his enemies seeks refuge in the mother earth. Interestingly, the fire ordeal of Lakshman is ordered at the behest of Sita who suspects Lakshman of dalliance. In some versions he himself offers to undertake the trial to refute the allegation. In another tale the role reversal is almost complete and climatic when at the behest of Sita, Lakshman disguised as a women goes to Lankagarh to kidnap Ravan’s daughter in order to marry her.

The Gond Ramayani is usually sung at night after performing a ritual that is believed to facilitate assimilation of dead relatives with the main Gond deity, Badadev or Budadev. This ritual is performed once in three years for all those relatives who may have died during this period. At night the visiting Pardhan sings stories from Pandvani, Gondvani or Ramayani3 as per the inclination of his jajman. This is done for peace, happiness and repose (sukhshanti ke liye) of those who have passed away in these three years, and for the purification of the house. However, these stories can be sung on occasions of marriage and birth, or for the sheer pleasure of listening and also to remove pollution caused by death in the family soon after the cremation has taken place.

Pardhans are considered to be the descendants of the youngest brother among the seven primeval Gond brothers, who were born to Parvati, but since they stank so much Mahadev locked them up in a cave. However, four of them managed to escape and went to live in Lohagarh. Later Mahadev created a boy from a flowering tree, who grew up playing on a bed of saffron, and drinking nectar from the flowers. He made a musical instrument called bana from a Khirsari tree and played melodies on it. He came to be called Lingodev4. Lingo later became the main deity of the Gonds. However, the stories of Lingodev are almost forgotten in Mandala and Dhindori regions and he has gradually come to be identified with Budhadev and Badadev. Budhadev is the first ancestor of the Gond clans and each clan has its own Budhadev. Each clan also has in the village of its origin a Saja tree, in which Budhadev is believed to reside. Every three years a ritual is conducted to assimilate the souls of the dead with Budhadev. Over a period of time, Budhadev has been merged with another deity Badadev, who too resides in the Saja tree and is one of most significant deities of the Gonds. The Gonds often refer to Badadev and Budadev as a single deity and boundaries between the two are fuzzy. Budhadev, Badadev, Lingodev and their stories have a strong bearing on the Gond Ramayani though none of them has a direct presence in the text. I shall keep returning to these deities throughout this essay, particularly to Lingodev and his story.

Pardhan Gonds, are hereditary singers and genealogists of the Gonds. It is held that they were assigned this task by Badadev. He once became angry with the Gond brothers for throwing stones at him and hid himself in a Saja tree. He was appeased only when the youngest brother played on the bana. Badadev then declared that the youngest brother would not have to till the lands anymore; he will serve as the hereditary priest of the Gonds, who will provide for all his needs.

The seven tales of the Ramayani are: Lakshman’s trial by fire to prove his innocence; Abduction of Lakshman by Indarkamani; Lakshman and the beautiful daughter of Indar – Tiryaphool; Lakshman and Princess Machladei; Lakshman and Ravan’s daughter – Rani Puphaiya; Lakshman and the daughter of Vasuki – Bijuldei; and Banishment of Sita. The Gond Ramayani in its entirety was first compiled and published by Sheikh Gulab in 1964. In 2019 it was published by the IGNCA with translation in Hindi by Roop Singh Kusram and Vasant Nirgune with an introduction by me. Varrier Elwin printed parts of it in his collection of Baiga tales and some parts of it were later reproduced in a volume Folk and Tribal Ramayanas by the Anthropological survey of India in 1993. It was recorded by the IGNCA first in 2011-12 and again in 2019. The narrative that Elwin and Anthropological Survey of India published is that of Indarkamini, who falls in love with Lakshman and subsequently abducts him. She keeps him captive in her palace in Indarlok. In the morning she turns him into a Billy goat and at night into a man. Lakshman is later rescued from this captivity by Ram, Sita, Hanuman and the Pandav brothers. The story then goes on to narrate another tale in which Lakshman is sent on a journey to marry Macchandar Kaina, daughter of Macchandar Raja of Kalsapur5. In this essay I will focus precisely on this tale, which appears as three different tales in Sheikh Gulab’s version; and once again as a single tale in one of the later recordings by me. In the version that I recorded in 2019 at the IGNCA from the Gond Pardhan singers Maravi and Dhurve the two characters that of Indarkamini and Tiriyaphool have been merged together. It has also incorporated parts of the tale about Machladei. Machaladei is the name of Machhandar’s daughter.

It is this interlinking of different tales and the merging of characters that holds our interest here. It helps us understand the inner workings, cohesiveness, and multiple levels at which the Gond Ramayani can be read both in conjunction with the Ramayan story and as an independent narrative. Let us begin with the story as given in Sheikh Gulab6.

“In Ayodhya lives Ram in his madan mahal and in jhinjari mahal lives Sita. Away from all, lives Satyavan (the celibate) Lakshman. It is difficult to measure the strength of his truthfulness. He has never plucked a blade of grass, never spoken to a stranger women, never stood under a withered tree, never relieved himself in a field of sesame seeds, has never peeped into a blind well. Oh, please don’t tell me about it. I already know how chaste and pure Lakshman is!”

So the beginning is set with an emphatic and detailed statement about Lakshman’s celibacy. The singer now moves onto describe his dwelling:

“He lives in dunda mahal (palace made of a withered tree) guarded by sun and moon at every twelve kos. Every thirteenth kos he is guarded by Dhalua, the demon. Lions and bears guard his gates. Twelve dali (branches) full of wasps, thirteen dali full of honeybees, fourteen dali full of red ants, and scorpions with raised pincers stand guard at fifteen points. At sixteen points stand guard the bees with poisonous stings. My Satyavadi Lakshman is guarded so well! He sleeps on a bed, which has Sheshnag as the legs and Dhaman naag as posts. Silken tassels hang down from its frames. Scorpions serve as nails while the python forms the pillow. Lakshman’s feet are protected by jewel crowned snakes making up for the quilt. His scarf is made of red ants and tiny snakes”.

In this palace, Lakshman periodically gets into a sleep cycle that lasts for twelve long years. Once when he woke up from one of his sleep cycles he thought of getting himself a kinnar baja, a musical instrument that accompanies the singing of epic tales. So he went to a carpenter and got himself a baja made. Returning to his palace he hung it on the wall and promptly went to sleep — an uninterrupted twelve years long sleep. Now the baja is bored and laments his fate. He becomes restless and enters into Lakshman’s dream and complains, warns and threatens to go back to his companions in the forest. Lakshman wakes up immediately and pleads with the baja not to leave and begins to get ready to play the baja:

“He dusts his baja, sweeps his palace, spreads the deerskin and places eighteen kinds of musical instruments on it, sends invitations to nine hundred doves and pigeons and takes his seat. The pigeons and doves arrive dancing. On feathers of the pigeons he ties bells, in their beaks he places cymbals, on their feet the ankle bells. He himself supports ankle bells on his feet; tinkling bells on his toes, and on his big toes he ties the cymbals; small drums are tied to his knees; on his waist he has large rattles and from his shoulders hangs the tambourine; bells hang from his ears; he plays the flute with his nose; he hold the kinnar baja in his hand and plays on all the eighteen instruments together. The palace is filled with the sound of music; all eighteen instruments are played together. The palace with its tightly shut eighteen doors and fifteen windows, neither lets the air come in nor lets it escape to the outer world. The palace is unable to contain the sound. Breaking open the ceiling the sound escapes and reaches Indarlok”.

What a powerful visual imagery! Who is this yogi? Lakshman Sati/Jati, the preferred hero of tribal Ramayans, who spent fourteen years of exile as a celibate while surviving on just soil? Or is he Badadev himself playing on his bana? Or is the music a call to a mate or the sound of life itself? Nor can the tantric interpretations of the body be ignored here. The dunda mahal — the palace made of a stump of a tree — inside which Lakshman, the celibate sleeps for twelve long years — is something we will come back to later.

Lakshman is not the only one among the Gond heroes who plays on eighteen musical instruments tied to his body. The other such player is Lingodev. Lingodev is invoked in the following manner:

Oho! Lingodev has eighteen bajas

Singi baja is hanging from his shoulder

Tied to his waist is Parai dhol

Paijan Rai is tied to his ankles

Dhusir Rai (Chikara) is tied onto his chest

He is playing on Jhikar Rai (Morchang) with his nose

And Sular Rai with his mouth

Johar to Him!7

Interestingly, the dormitory in which Lingo lives is also not very different from that of Lakshman, but more of it a little later. For now, let us return to our story.

The sound of the baja reaches Indarkamini, the daughter of Indar, who is playing on the swing with her companions in Indarlok. She is restless; her companions are restless. They are enchanted. Indarkamini can no longer contain herself. Her friends begin to shed tears seeing her mental state. They advise her to go and bring the player of the baja to her palace. What follows is a very detailed description of her ornamentations and her journey, which is full of escapades. I leave this big chunk out here and take you directly to the point when she reaches near Lakshman’s palace and, turning into a fly, enters his palace through an opening in the rooftop, which had formed when the sound escaped to the outer world through the ceiling. Sat, the sexual control over his body and senses by Lakshman, is severely under threat. The sound of music emanating from him has invited trouble. But he falls asleep before Indarkamini can reach him. Indarkamini, this daughter of Indar, has another name, Tiriyaphool, who is depicted as a floating flower in the pond in the later part of the tale where Lakshman tries to woo her. Tiriya means woman and phool means flower. The flower woman that he has been so diligently avoiding up till now is knocking at his door bewitched by the sound his body makes. Indarkamini tries to wake him up, she embraces him again and again, showers him with kisses, shouts into his ears, shakes him violently, tries to make him sit up but to no avail. She is desperate and frustrated. In her frustration she tears apart her clothes, breaks her bangles, pulls out her earrings, scatters her ornaments all around on his bed and on the floor; then, turning into a fly she sticks herself against a wall and exclaims, ‘Oh my sworn enemy I will wait here till you wake up!’

Is it really Indarkamini, or the intense desire within him, that Lakshman had managed to bridle up till now? Perhaps yes, perhaps no! In the meantime Sita is filled with the desire to meet her beloved brother in-law and decides to go and look him up. In some tales in the cycle it is Lakshman who heads straight for her palace after waking up from his twelve years long sleep as he has begun to miss her intensely.

Sita in her palace is talking to her companions:

“Lakshman, my darling brother in-law is the kohl in my eyes, vermillion in the parting of my hair, he is the silken tassel hanging from my hair bun. Ram and Lakshman are like two udders of a cow, but neither my husband nor my brother in-law cares about me. Let me go myself and meet my brother in-law”.

It is interesting that Sita chooses to visit Lakshman and not her husband. Nor are her endearments addressed to Ram. The journey to Lakshman’s palace is not an easy one. She crosses:

“Dense forests, high mountains, rivers, ponds and wetlands, marshes and swamps! She crosses them all one by one. Sweat is dripping down her forehead. Burning earth under her feet and scorching sun above her head, but she doesn’t give up”.

Finally she reaches dunda mahal and rushes inside. But what a shock awaits her!

Satdhari Lakshman!

Vratdhari (diligent in keeping his vow)

Lakshman, who moves faster than wind!

Lakshman full of honour and pride!

How did he sway from his truth?

What has happened to you Lakshman?

She hurries to reach her husband’s palace and informs him of what has happened. Pandavs are called, all the gods are called, Sehdav reads from his all-knowing book; and together they leave for dunda mahal. Ram leads and Sita and the Pandavs follow. Gods follow, Raja Vasuki follows and armies follow. Ram is enraged at what he sees inside Lakshman’s palace and shakes his arm forcefully. Lakshman wakes up and is perplexed to see them all gathered around him. He is asked to explain why there are torn female garments and ornaments in his chamber and why he deviated from the path. Lakshman begins to cry and tears begin to flow down his cheeks. So Narad, and in some versions Sita herself, orders the trial by fire for Lakshman. lohars (blacksmiths) are summoned from Lohagarh8 at Ram’s commands, who tells them:

Listen carefully!

On the borders of the kingdom construct a palace made of iron

With iron bricks and iron mud.

Let the pillars be of iron and

And the beams be of iron.

So the palace is constructed on the borders of the kingdom with

Iron bricks and iron mud

Walls of iron and beams of iron

Poles of iron and roof tiles of iron

Iron threshold and shutters of iron

The gates are of iron too, my brothers!

The palace is then covered from outside with nine hundred mounds of wood.

Lakshman is now asked to enter this palace and prove his chastity. Weeping, he takes down his kinnar baja. With his nine hundred doves and pigeons and eighteen musical instruments tied to his body he enters the iron palace. Palace doors are shut behind him and it is set on fire. People begin to cry:

“Lakshman will be burned to death. Even his ashes won’t be found. Storms will blow away his ashes. No sign of Lakshman will remain”.

While people are thus weeping and wailing outside, inside the burning iron palace on the borders of the kingdom, “it begins to drizzle; cool breeze begins to blow. Grass puts out shoots and the ground turns green. Nine hundred doves and pigeons begin to dance. Lakshman plays his baja sitting on the green durva grass. It begins to get freezing cold inside the burning iron palace and Lakshman’s teeth begin to clatter”.

To cut the story short, Lakshman’s chastity is proven and everyone goes back home. Back in his palace Lakshman falls asleep. Indarkamini abducts him and takes him to Indarlok. There she turns him into a Billy goat. Indarkamini and her friends harass him mercilessly. In the morning they have lot of fun at his expense and at night turning him into a man, they make him dance with them (Nankusia Bai.1). His strength begins to wane and he begins to lose weight. Realising that he is nearing death, he “enters into Sita’s dream” and informs her of the grave danger to his life. “Come and rescue me or else I shall die at her hands”. Sita narrates the dream to Ram; Pandavs are called, Mahadev and Parvati are called; landlords and kings are called; and Hanuman is called. Sehdev reads from his all-knowing book. All of them decide to wage a war on Indarlok.

“Elephants, horses and camels are gathered and war trumpets are gathered. Tents are folded and armies are gathered. The battalion marches ahead with elephants, horses and camels, spears and tanks, rifles and trumpets. War drums thunder, and the emblem flies high”.

Reaching Indarlok they hatch a plan and kill all the goats overnight barring the one in Indarkamini’s palace. Now Pandavs turn into musicians and dancers and reach Indar’s court. In all this planning Narad is their advisor. I am giving here a very condensed version. The actual story, with all its visual imagery in the detailing of the scenes, moods, expressions etc. stretches several pages containing several episodes and events.

The Pandavs sing and dance in the court of Indar. He is pleased with their songs and dances. In return, they ask for a living goat to be given to them. The only living goat left in his kingdom is the one with Indarkamini. It is given to the Pandavs and they bring it back to the camp. Indarkamini, turning into a hawk pursues the chariot of Ram in which he is seated with Sita. With her beak, she destroys the chariot and grievously wounds the charioteer. A fierce fight ensues. Ram is deeply wounded and defeated9. Sita and Indarkamini begin to fight now on the ground. They pull at each other’s hair and slap each other; blows are exchanged and abuses hurled. Finally, Narad agrees to arrange for the marriage of Indarkamini with Lakshman. It is a trick. Indarkamini is unaware of this. She is taken in by the promise. The fighting comes to an end and the scenario changes. Idarkamini falls at Sita’s feet. Laughing, she embraces Sita again and again. She is beside herself with joy. Finally, she is tricked and imprisoned behind the eighteen doors. Where she is locked up till date. She hisses inside and her hissing spreads cholera in the world. The singer concludes with the phalashruti.

“Like, Lakshman, let everyone’s sat remain steady!”

Who is this story really about? Why is there rivalry between Sita and Indarkamini? Is it about two women fighting over a man they both desire? Is it about the Oedipal conflict? Is it about two people fighting their inner ghosts of desire and passion? Is it about anxiety, suspicion, and tension that Gond society experiences because here the younger brother shares a very close and intimate relationship with his elder brother’s wife? Or does it reflect the anxiety of the young bride who sees her elder sister in-law as a threat and a rival? There are folksongs reported from the region where a young bride is afraid that her marriage may not succeed as her husband is under the lure of his brother’s wife.10

In one of the versions from the neighbouring Baigas, with whom the Gonds share an intimate relationship and who till date perform some of their ritual ceremonies, the bangles left by Indarkamini fit only Sita. Ram is enraged. Lakshman offers to undergo trial by fire. Not satisfied with the first one Ram orders a second one. Lakshman passes the test but once his innocence is established and Ram is pacified, he out of grief requests mother earth to open up. She unfurls her heart and Lakshman enters it.11 In one of the versions narrated by Maravi and Dhurve too, the bangles left behind by Indarkamini only fit Sita.

Lakshman in the Gond Ramayani is not portrayed as a man of any exceptional valour. In fact valour actually is of no concern here. For this the Ramayani has chosen another hero i.e. Hanuman. Pushed by Sita, Lakshman keeps venturing out to win a bride for himself, and gets into great difficulties and situations that threaten his life. He then appears in Sita’s dream and asks to be saved. Each of these tales ends with an assertion of Lakshman’s sat. For Lakshman to qualify as a hero he has to repeatedly provide testimony to his purity and celibacy.

However, for the Gonds themselves marriage is the most important and significant event. Even the Gondvani, the narratives about Gond Rajas, mostly narrates stories about their various quests for a bride. The practice of young lads staying with their future father in-law and serving him in various capacities for a long period of time has social sanction. So Lakshman, who shuns marriage despite all the temptations, may seem to appear heroic. His celibacy or sat is the only quality these tales underline repeatedly.

Let us move on to our next tale and see what transpires. I have two versions of the story, one from Sheikh Gulab and other sung by Maravi and Dhurve. I take up the latter one here in brief.

Once after waking up from his twelve-year sleep, Lakshman thinks of visiting his sister in-law and leaves for jhinjri mahal, where Sita is sitting on her swing accompanied by her friends. When they see Lakshman they request Sita to pretend that she has not seen him so that they can have some fun at his expense. When Sita refuses to acknowledge his presence even after his repeated entreaties, Lakshman takes offence. Sita now tries to pacify him. She offers to prepare food for him but Lakshman asks for items that Sita has never heard of. These are ordinary items but Lakshman asks for them in a riddle form and Sita goes looking for them. The first item is of special significance to us. Lakshman asks for bhrun ka lachha (sap of bhrun grass). Significantly, bhrun is a reed, which is used in the ritual of assimilation of the dead with Badadev. The spirits of the dead are believed to reside in this reed and it is thrown away in the water after the ritual. (Bear this in mind as we proceed further.) Sita tries to gather the flowers from this reed, but her hands are wounded in the process. But when she returns with the flowers Lakshman tells her that this is not what he had asked for. He sends her to Viratnagar where she can find all the items needed to prepare his food. Sita is unable to find any in Viratnagar and begins to cry. Her feet are blistered. She is exhausted and distressed. Finally an old lady comes to her aid and solves the riddle. Sita cooks the food desired by her brother in-law, but Lakshman refuses to partake of the food because some drops of her sweat have fallen into it. Lakshman leaves. Sita is angry with him and begins to weep. Exhausted she falls asleep and has a nightmare. She wakes up screaming. Lakshman rushes to her aid. She narrates the dream to him, in which she saw him getting married to Tiryaphool. But as Sita leads him to take the seven circles around the sacred fire a demon appears and snatching Lakshman away from her hands disappears into the skies. (It is hard to resist a psychoanalytic interpretation of this entire episode). Lakshman consoles his sister in-law and promises to bring back Tiryaphool as his bride. Once he leaves, Sita is overcome with anxiety for his safety and rushes out to stop him from going. Lakshman refuses to go back with her and proceeds on his journey. On the way, he encounters a fig tree with ripened fruits. As soon as he tries to pick the fruit, the tree disappears and instead he finds Sita standing there. She tries to persuade him to return but he refuses and moves on. On his way he encounters a vixen feeding her cubs but when the vixen sees him approaching, she runs away leaving her hungry cubs behind. Lakshman is distraught at this and runs after the vixen, bringing her back he tries to put her udders into the mouth of her cubs. At this point, the vixen disappears and he finds Sita standing before him. But, he again refuses to go back with her. Further down his path, he begins to feel thirsty and finds a spring nearby; as soon as he tries to drink water, Sita reappears and again pleads with him to turn back.12

I leave out a big chunk from the narrative here. Lakshman, after several failed attempts, finally finds Tiryaphool swimming with her sisters in the form of flowers in a pond. He steals her clothes and promises to return them only if she would give her word to marry him. Smitten by him, she agrees to the proposal. Lakshman, however, loses her, when against all her warnings, he insists that she enters the pond once again and show him her flower form. Tiriyaphool enters the waters and turns into a flower again and is kidnapped by the king of Bumblebees. After much effort Lakshman reaches the kingdom of Bumblebees and tries to steal Tiryaphool, whom the king has hidden in a bamboo grove in Kajali Ban, the dark forest, made even darker by the swarms of bumblebees covering the entire forest. Lakshman manages to find the bamboo flower in which Tiryaphool is kept hidden. He plucks the flower and runs away. The king of the Bumblebees and his army of thousands and thousands of bumblebees pursue him. Swooping down on him in swarms, they attack him fiercely13. Lakshman runs for his life and prays to mother earth to open up and provide him shelter. Earth opens up and Lakshman enters. He appears in Sita’s dream and asks her to rescue him. Sita informs Ram. Pandavs are called for help. Sehdev reads from the all-knowing book and explains about Lakshman’s whereabouts. Armies march under Ram’s leadership, but no one is able to defeat the army of Bumblebees. Finally Hanuman comes to his rescue; kills all the bees and frees Lakshman. Back in the palace Lakshman is married to Tiryaphool. Leaving her behind with Sita, he leaves for his palace.

Of interest here is also the fact that the bees, which had guarded him in his palace of eighteen tightly shut doors and fifty-two closed windows, now sting him mercilessly to the point of death for desiring the flower woman. Sita comes to his rescue and he is saved from death by another celibate, Hanuman. In fact in all these tales, Lakshman’s celibacy is always put under trial and he is unable to protect himself unless Hanuman comes and saves him.

Let us briefly shift our attention to Badadev and Lingodev. Both Badadev and Lingodev as we already know share several traits in common. Both are linked with music and manifest themselves in the form of their musical instruments. Both are associated with the processes of life and death and are closely associated with the youngest of the seven primeval Gond brothers. Lingo, in fact, is the youngest of the Gond children of Shambhu Shaik (Shiva) and Parvati. Lingodev, in different versions gathered from different sub groups of the Gonds by Elwin,14 is the one who assembled all the primeval Gond groups and distributed them into phratries, clans, sub-clans, introduced them to fire and cultivation, started the institution of youth dormitories (ghotuls), taught them music and dance as well as gifted the bana to them. At one level Badadev, Budadev and Lingodev are extensions of one another and, by analogy, the Pardhan Gond, who is the youngest of the seven primeval Gond brothers and the only one to have been bestowed with the bana, is an extension of Lingodev and Badadev.

Let us return to Lakshman who also shares several traits with Badadev and in particular with Lingodev. Like the Saja tree, his dwelling has shut out all that is living. In this dwelling, he lies asleep for years till the bana calls out to him and he wakes up. Here it is hard to miss the similarity between him and Badadev. Similarities between Lakshman and Lingo are even more pronounced. Lingo had suffered at the hands of his sisters-in-law when he spurned their advances. Like Lakshman, he too was asked to prove his purity by undergoing several trials by fire. The story goes like this: the wives of the seven brothers are infatuated with Lingo and try to seduce him. When Lingo resists their advances they accuse him of molestation. As proof they bring their torn garments to their husbands and show them the scratches on their bodies, which they supposedly received while defending themselves against Lingo’s attack. When Lingo denies these charges, he is put to test. There are several versions of this trial by fire. In some, he is pushed into a burning fire and he dies but is revived later by Mahadev. In some others, he is locked inside an iron box. A furnace is prepared with several tons of wood at the borders of the village. The iron box with Lingo locked inside is thrown into the burning furnace but no harm comes to Lingo, he sits inside playing on bana, while cool breeze blows around him. In another version Lingo is imprisoned inside a Saja tree, which is then set on fire. Lingo is found inside playing on his eighteen musical instruments unharmed.

Lingo in some versions is shown to be a celibate and in some others he marries seven wives, but like Lakshman resides with none. He lives away from them in the ghotul. Lingo’s ghotul is also not very different from Lakshman’s bedchamber.

Lingo’s ghotul is beautiful like the horns of a buffalo

It is as beautiful as the neck of a horse

Inside the ghotul the python stands right in the centre as the main supporting pole

Mahamandal snakes are the pillars supporting the roof

Dhaman Nag forms the roof beams, Cobra provides for the ceiling and its poles.

The floor is plastered with the flour of Black Gram, while the crocodile provides for the stool

A swing made of Saja tree hangs from the ceiling

With the help of ropes made of snakes

Sitting there Lingodev is playing on his eighteen musical instuments,

They possess the power of the vashikaran mantra (a spell to bewitch/ enchant someone)

Young men and women under its spell come running to the ghotul.15

Significantly, Lingo’s ghotul is called dinda mahal, palace for the unmarried. Lakshman’s palace is dunda mahal and he too is unmarried. He too, in his palace surrounded by snakes, scorpions and wasps, sits playing on his eighteen instruments. Bewitched by the sound of his instruments, Inderakamini comes flying into his palace. The resemblance between Lingo and Lakshman can go no further. It is complete.

Let us now look at the dwellings of Sita and Ram. She lives in a palace, which is called jhinjari mahal. It has holes, openings and provides easy access inside. Air circulates through it, and there are no guards. Sita lives with her companions in the palace. There are swings and laughter inside. But most significant of all is the free circulation of air inside. Ram lives separately in madan mahal –– royal palace made of gold and silver in a city of gold, with market spaces and townships and people bustling about. In his palace regular courts are held that debate and resolve civil and legal matters. Both the humans and divine attend these courts, but interestingly it has no female presence here. Sita only occasionally visits the palace.

The Gond Ramayani thus presents us with three different worlds. Ram’s palace is the world of order, civility and propriety. It deals with the mundane and is focused on maintaining order, ethics and moral code, and provides defense against threats both from the enemies outside and moral decay inside. It is not accidental that Sita is always rushing to his palace to rescue Lakshman. But Ram never acts impulsively, before taking any action he consults the Pandavs and hoard of other deities. He makes Sehdev read from his all-knowing book and unless the truth is established this way he never ventures out to retaliate. His portrayal is very much in sync with Ram’s character in the more canonical renderings of the Ramayan story. Lakshman, the celibate removed from life and its pleasures, is part of the world of the dead and like Badadev wakes up only when the bana is played. When he wakes up from his periodic twelve year sleep cycle, he either plays on the bana or seeks his sister-in-law. This encounter with Sita always ends with a journey to find himself a bride. In these tales, Sita neither tests nor protects Lakshman’s celibacy.

Sita in her jhinjri mahal is the life-breath like the bana. Her palace of circulating air, and orifices/openings is also like the bana, invoking life and its pleasures. It represents the life invoking sound of music.16 Lakshman’s attraction towards her at one level is attraction to life, to all that is living. Sita, her palace and bana are extensions of one another by the same analogy as Badadev, Lingodev and Pardhan bards are. If we stretch the analogy a little further, Lakshman is an extension of the Pardhan Gond.

At this level these tales seem to inhere the perennial tension between life and death. This, however, is only one of the many ways these tales beg to be read. At another level it is fascinating to read them as tales about the Oedipal conflict with displaced projections and its resolution through a vow of celibacy and the renunciation of pleasure.17 This also explains the inner logic of all the other tales in the cycle and especially the role of dreams in these tales. In the Gond Ramayani, Sita seems to be forever dreaming about Lakshman marrying some distant princesses. In some tales, she pushes him to find a bride for himself and in others she tries to ward him off these misadventures. However, Lakshman pays no heed to her words. Every time he ventures out to find himself a bride, he is overpowered by powerful, aggressive father figures (except in the case of Indarkamini onto whom the Oedipal desire is projected. She appears as a castrating, devouring female)18 till Sita intervenes but only after he has sought refuge in mother earths’ wombs and gains entry into Sita’s dream, back into an infantile state. Leaving his brides with Sita in jhinjhari mahal, or loosing them in one way or the other, Lakshman returns to his dunda mahal and falls into his twelve years long slumber. Ram also retreats into his madan mahal after the conflict has been resolved and reconciliation brought about.

Lakshman is safe as long as he is unaware of his own sexuality, but the moment he wakes up the demands of his body lead him into situations that threaten his very life. He can be saved only through the intervention of two figures — Mother like sister-in- law, Sita, and the celibate, Hanuman, who is totally devoted to Ram. Read in this way, all the brides are projections of Sita and all pursuing aggressors are extensions of Ram. Sita’s dreams are her anxiety over the growing sexuality of her son like brother-in-law. The conflict is resolved through complete denial of sexuality and celibacy on the part of Lakshman, while Sita tries to push him towards a normal adulthood and accepted norms of gratification of desire. At another level, these tales may be connected to the killing of Lingodev by the primeval Gond brothers, and through them the Gonds try to rework a deep seated guilt of patricide.

Dreams play a very important role in these tales. They have dreams as their beginning and end points; dreams that bring to the surface social and sexual anxieties. It would be worthwhile to investigate the dream culture among the Gonds to discover further layers of meaning that the Gond Ramayani encodes. Interacting with the larger mythological repertoire of the Gonds, it reworks and recasts several of its archetypes and motifs and presents us with a narrative laden with multilayered symbolism and multi-level discourse built around psychosocial aspects and philosophical contemplation on the human body, sexuality, asceticism and desire, life and death. It would be more fruitful to focus on this discourse rather than search for its archetypes in the Ramayan.

***

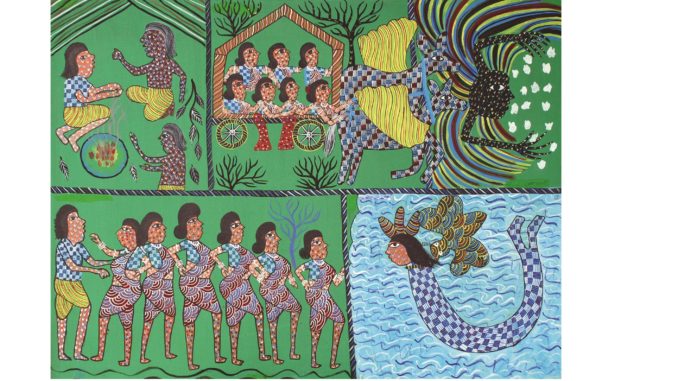

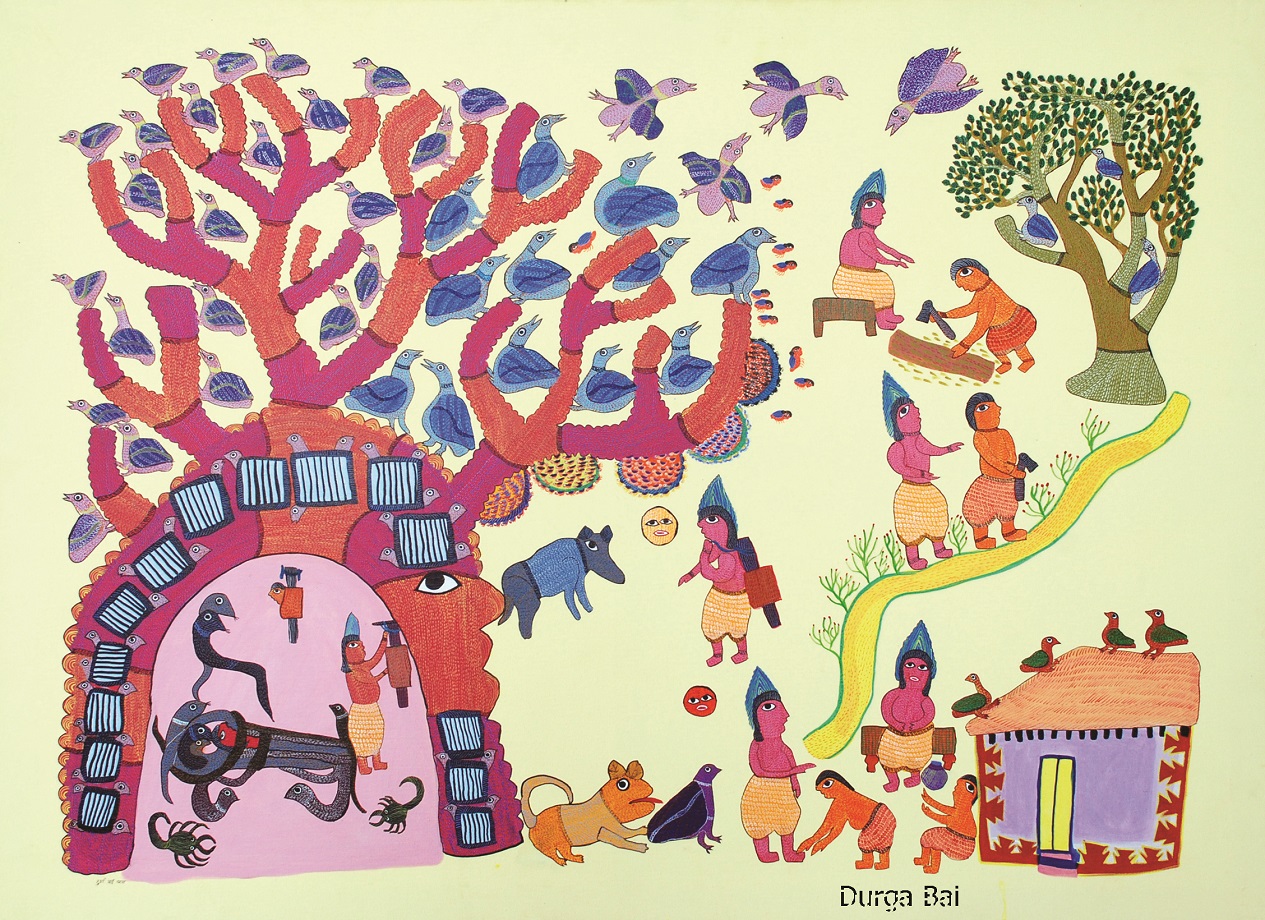

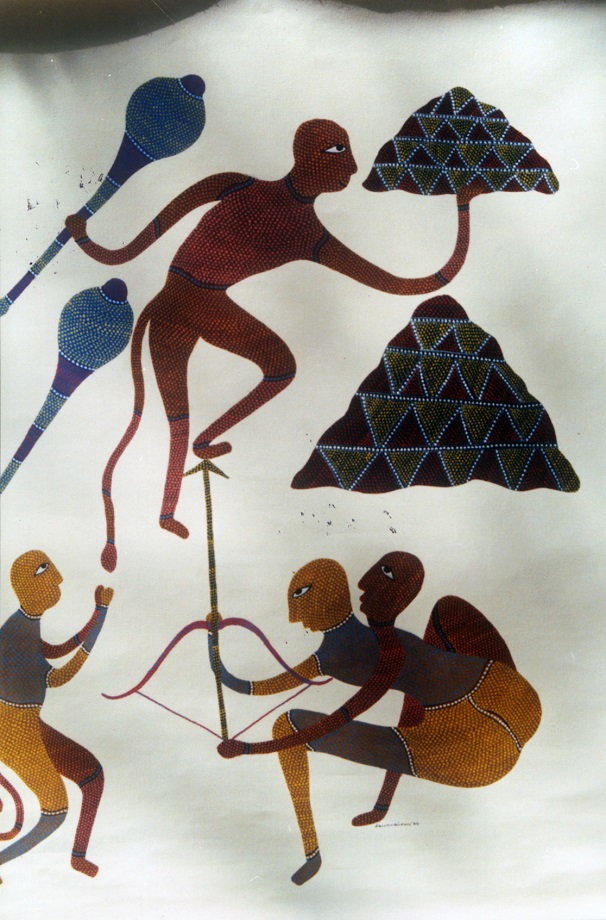

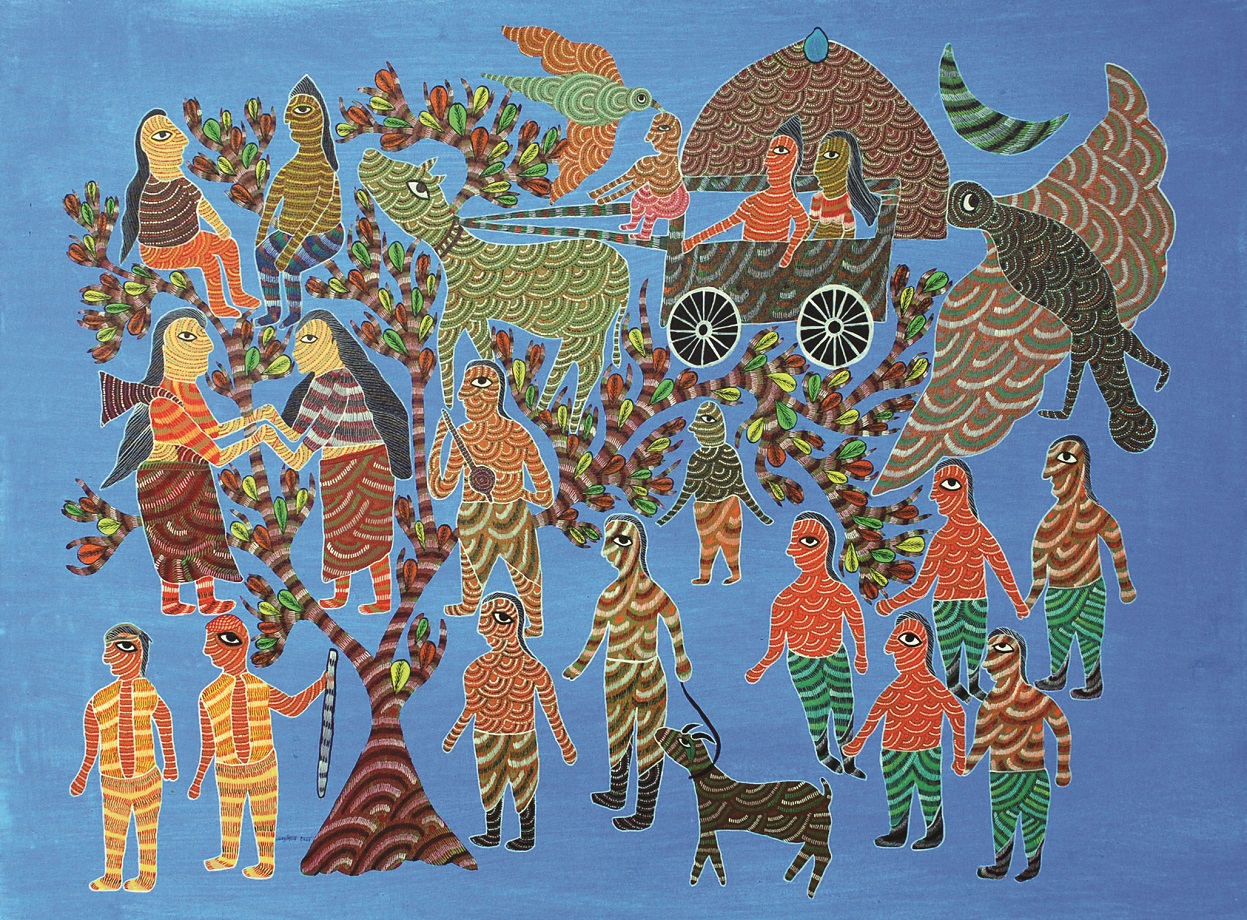

The paintings on Gond Ramayani that accompany this essay are a part of a much larger set of paintings done by different Gond painters in a workshop organized by the IGNCA, otherwise it is rare to find Gonds painters engaging with the Gond Ramayani as their subject matter. In this workshop the Gond painters selected one tale each and together produced a set of 34 paintings covering the text in its entirety. Each painter left his/her own unique creative mark on the paintings while working within the school that has come to be known as Jangarh Kalam named after its founder, Jangarh Singh Shyam.19

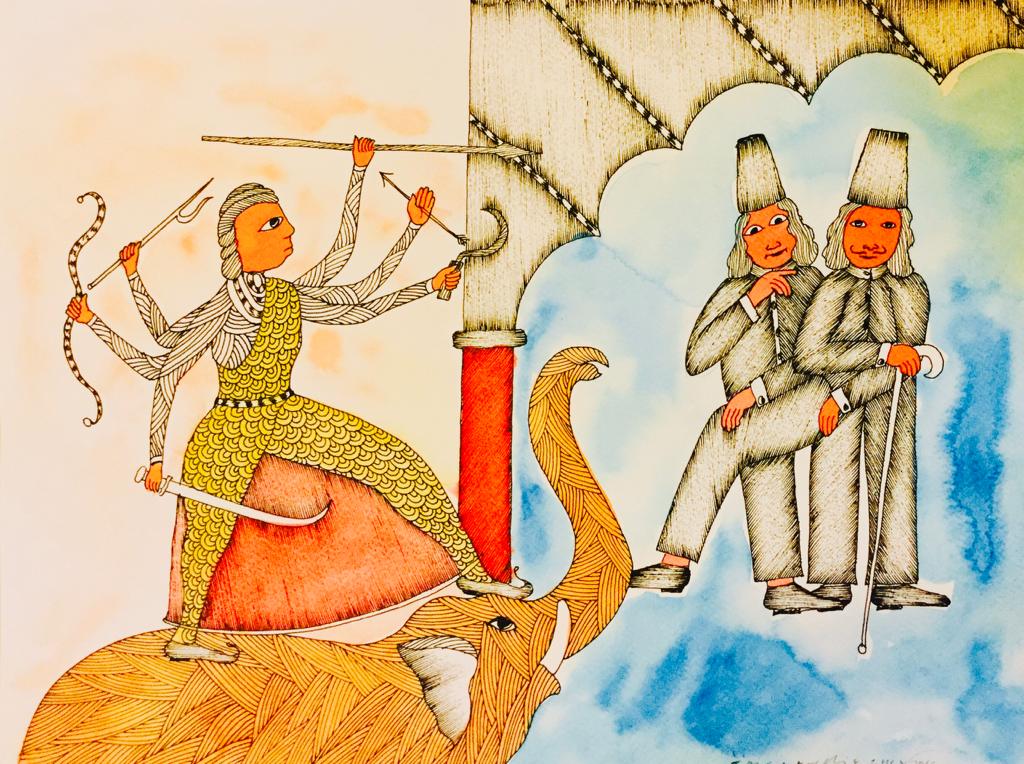

I have also included here some of the painting by Venkat Shyam, a well-known Gond painter. He was not a part of this workshop, but his paintings are of interest as they deal with the canonical versions of the Ramayan story. However, in one of his earlier works he has painted Lakshman’s bed made of snakes and python.20 Later he made some wonderful paintings based on the Ramayan story. His two paintings based on Kevat episode stand out for delicate contours of its characters and tranquility that surrounds them.

There appears to be an influence of calendar art in the stylization of these characters. He has also painted several images of Hanuman. One of his paintings with Meghnath depicted as Shakti is outstanding. Meghnath here resembles the many-armed Durga. Venkat’s paintings here reflect his contemplative journey and inner dialogue with the tradition, and contemporary identity discourse among the Gonds.

Notes:

1. Richman; 2015, pp.35-36.

2. It was earlier well known in the Chhattisgarh area as well but now it is hard to come across people who know the story.

3. Pandvani is the oral epic about the Pandavs, and Gondvani is a cluster of sung narratives about the Gond kings.

4. The cult of Lingo has gained much popularity in Chhattisgarh in recent times and efforts to revive Lingo worship in the region are closely linked with the identity assertions by the Gonds.

5. Macchandar Kaina in another version appears as Machladei

6. English translation of all excerpts from Gond Ramayani are by me and translated from the original text complied by Sheikh Gulab and reprinted by the IGNCA in 2019, unless otherwise indicated.

7. Elwin 1947: pp. 177.

8. Let us recall the four Gond brothers who escaped to Lohagarh — the Iron city. Lingo was put to test by these very brothers and burnt alive by them.

9. Cf. Jatayu-Ravan fight in the Ramayan.

10. Mahendra Kumar Mishra (1993;pp.15-33), a folklorist who has done extensive work among the several tribal communities in this region, in his essay on folk and tribal Ramayans reports several verses hinting at such relationships. Unfortunately he does not specify the exact community of Gonds from where the following verses have been collected:i) O companion, a young lad brought new wife but because of his liaison with his elder sister in-law, he forgot his new wife.ii) I entered the dark room to dry the paddy, not knowing that brother in-law was resting there. He embraced me and my nose-pin fell. Picking up the nose – pin, he kissed me.

11. Elwin 1939; reproduced in Folk and Tribal Ramayanas by Anthropological Survey of India, 1993.

12. Cf. Sita admonishing Lakshman harshly and sending him after Ram in the canonical versions of the Ramayana story.

13. Bumblebees occupies a very important segment of the Gond Ramayani, as is clear from the Tiryaphool story. Bumblebees are also very special to the ghotul life. Ghotul youth first became aware of dance and sex through the bumblebees whom they encountered in many of their forest outings. The first sound of ghotul dance is also borrowed from the humming sound of the bumblebee. (Marai, 2002, pp. 163-64).

14. Elwin in the 8th chapter, ‘’ The Legend of Lingo Pen,” of his book Muria and their Ghotul includes several versions of the Lingo story (Elwin, 1947: pp. 225-265).

15. Elwin 1947: pp. 253.

16. It is pertinent to note here that Lingo, after receiving the training in Music from Guru Hirasuka, retreated to a secluded hill for twelve long years where he led an ascetic life devoted to perfecting his training in music. Music plays a very important role among the Gonds and is intimately connected with life. In fact, in order to free his other Gond brothers from the cave, Lingo takes the help of music and his music teacher, Hirasuka. Gond children gain strength from music and bring down the rock blocking the cave mouth. Music represents life and forces of regeneration and renewal. This is already clear from the story of Badadev. (Marai, 2002).

17. For more on this and a detailed discussion of displaced projections or negative Oedipal conflict stories in Sanskrit literature and epics and different forms of its resolution, including celibacy as one such form, see Robert Goldman’s essay, “Fathers, sons and gurus: Oedipal conflict in the Sanskrit epics,” 1978.

18. For examples and analysis of castrating erotic female characters in mythology see Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, 1980.

19. For a detailed discussion on these paintings see Kaushal, 2015 and 2019. I am grateful to John Bowles for sharing with me a photograph of this painting and allowing me to use it for this article.

References:

Elwin, Verrier. 1947. The Muria and their Ghotul. Bombay: Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford University Press. Fuchs, Stephen. 1960. The Gond and Bhumia of Eastern Mandla. Calcutta: Asia Publishing House. Forsyth, Captains J. 1889. The Highlands of Central India: Notes on their Forests and Wild Tribes Natural History and Sports. London: Chapman and Hall Limited. Furer-Haimendorf, Christoph. 1948. The Raj Gonds of Adilabad. A Peasant Culture of the Deccan. Book I, Myth and Ritual. London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd. Goldman, R.P. 1978. “Fathers, Sons and Gurus” in Journal of India Philosophy, Vol. 6, No.4 (December 1978), pp. 325-392 Hivale, Shamrao and Elwin Verrier. 1935. Songs of the Forest. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. Hivale, Shamrao. 1946. The Pardhans of the Upper Narbada Valley. Bombay: Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford University Press. Kaushal, Molly and Tiwari Kapil . (Ed.). 2019. Gond Ramayani. New Delhi: IGNCA Kaushal, Molly. 2015. “Gond Ramayani : In Text and in Painting” in Molly Kaushal, Alok Bhalla, Ramakar Pant (Eds.). Ramkatha in Narrative, Performance and Pictorial Traditions. New Delhi: IGNCA and Aryan Book International, pp.242-250. Kaushal, Molly. 2004. Gond Paintings of Madhya Pradesh: An Interface of Tradition and Modernity (unpublished report). New Delhi: IGNCA. Marai, Thakur Komal Singh. 2002. Gondwana Bhukhand ka Prasangik Kathavastu. Bhopal. Akhil Gondwana Gondi Sahitya Parishad. Mishra M.K. 1993. “Influence of the Ramayana Tradition on the Folklore of Central India” in K.S. Singh and Birendranath Dutta (Ed.). Ram Katha in Tribal and Folk Traditions of India. Calcutta: Anthropological Survey of India and Seagull Books, pp.15-30. O’Flaherty, Wendy. Doniger. 1980. Women, Androgens and Other Mythical Beasts. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. Naik, T.B. 1993. “Ram-katha among the Tribes of India” in K.S. Singh Birendranath Dutta (Ed.). Ram Katha in Tribal and Folk Traditions of India. Calcutta: Anthropological Survey of India and Seagull Books. pp. 31-48. Richman, Paula. (Ed.). 1992. Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Richman Paula. 2015. “Ramkatha Alive in Performance” in Molly Kaushal, Alok Bhalla, Ramakar Pant (Eds.). Ramkatha in Narrative, Performance and Pictorial Traditions. New Delhi: IGNCA and Aryan Book International, pp. 31-45. Ramanujan, A.K. 1992. “Three Hundred Ramayanas. ‘Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation,’” in Paula Richman. (Ed.). Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 22-49. Singh, K.S. and Birendranath Dutta. 1993. Ram Katha in Tribal and Folk Traditions of India. Calcutta: Anthropological Survey of India and Seagull Books. Singh, K.S. 1993. “Tribal Versions of Ram-katha: An Anthropological Perspective” in K.S. Singh and Birendranath Dutta (Eds). Ram-katha in Tribal and Folk Traditions of India. Calcutta: Anthropological Survey of India and Seagull Books, pp. 49-66. Vajpeyi, Udayan. 2011. “From Music to Painting”. In Sathyapal (Ed.) Native Art of India. Thrissur: Kerala Lalitha-kala Akademi, pp. 32-83.