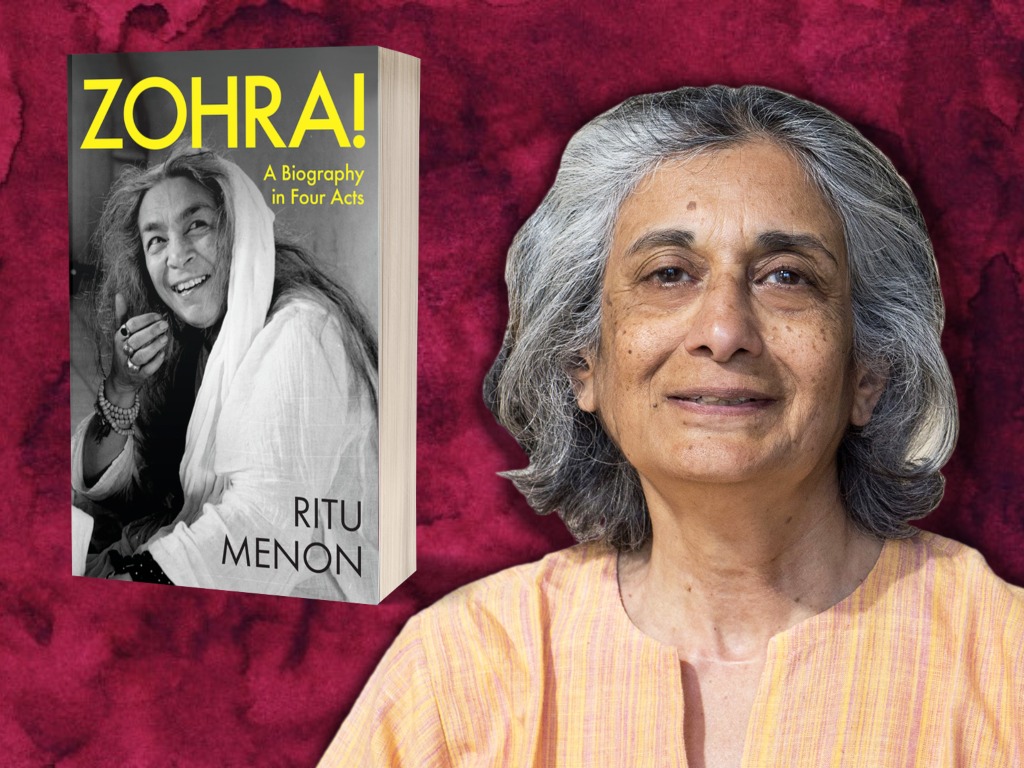

Zohra Sehgal (1912-2014) spanned an Indian century of the arts and became the only woman to make a mark in all the performing arts, with the exception of music, within the country and abroad. Feminist, writer and publisher, Ritu Menon’s Zohra! A Biography in Four Acts traces her remarkable journey — from travelling to Germany to learn modern dance at the age of eighteen, to playing the unconventional grandmother well past the age of eighty.

In this conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, Menon talks about the woman Zohra; the times or the context, whether in India or England; and the art of the biography.

Githa Hariharan (GH): The most obvious word that comes to mind when talking about Zohra Sehgal is unconventional, whether we consider her life choices in her times, or her work. Would you sum these up, bringing out the ‘breakthroughs’ but also the challenges and perhaps the less successful aspects of her achievement?

Ritu Menon (RM): Actually, more than unconventional, which she was, I would say she was truly courageous. It took a particular kind of courage, also confidence, to at 18, break the mould and strike out on her own. To enrol in a dance school in Germany, an unfamiliar country, without the language, without the cushion of family or friends, without instant communication — remember, this was 1938, not 2008.

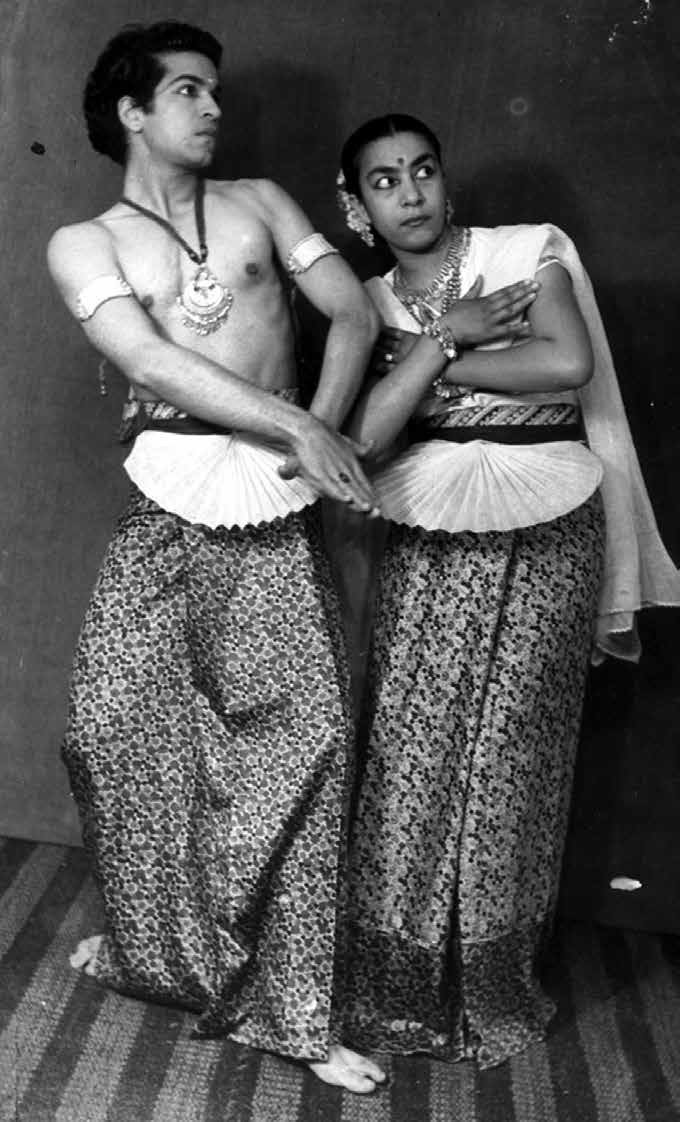

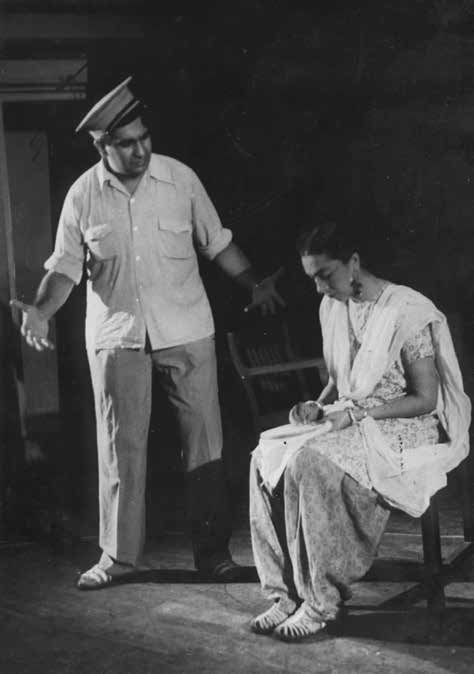

Rather than breakthroughs, I prefer to think of them as decisive moments that became turning points in her life. Joining Uday Shankar’s Dance Company and touring with him. Then, being part of Prithviraj Kapoor’s Prithvi Theatres. Zohra always said that it was Dada (Shankar) and Papaji (Kapoor) who were her inspiration, who were the creative power houses, and that she was lucky to have been at the right place, at the right time. On her part she intuited (or realised) that performing with them meant being part of something pioneering.

Her real challenges, both personal and professional, were what she encountered in mid-century England, as a 50-year-old Asian woman, a single mother, trying to make a breakthrough in a field that was notoriously cut-throat — and close-knit. It was actually in England, where she had no godfathers or benefactors, that she came into her own. Long before BritAsian became fashionable.

Also read | Zohra: An accidental actor

GH: Many of our readers will recall her as the mischievous and lovable grandmother figure. In some ways, this figure recalls the old woman from our tales who is free to say a great deal because of her age and perhaps because she is ‘liberated’ from the sexual space in the eyes of the conventional community. Do you think Zohra humanised this figure in ways beyond the stereotype?

RM: More than humanise, I’d say she rejected the Dadi stereotype, remade her as a character, and rescued her from becoming a cliche. And it was this irascible, wacky, unpredictable Granny whom audiences responded to, spontaneously, so much so that then roles started being written for her. There hasn’t been a granny like her in television, since.

GH: I want us to pay a little attention to her relationship, as a dancer and an actress, to the body as a medium, but also to language. Would you comment on the view that much of her power came from a trained body, her voice, and her way with words, from Urdu to English?

RM: Anyone in the performing arts, but especially those who go onstage, know that their body is their most vital asset. For Zohra, discipline, training, her riyaz, could never be compromised or neglected. It’s what enabled her to perform — and perform supremely well — till her late 90s. I don’t know whether her facility with English and Urdu contributed significantly to the strength of her performances, because really, it was her whole being that spoke — voice, gesture, movement, eyes, hands, stillness… In the film “Partition” she doesn’t speak more than a few words, but her performance is electrifying.

GH: In these jingoistic times, it is especially important for us to understand the value of a ‘hyphenated’ cultural life. How much of an interplay do you think there was between her work in India and in London?

RM: Not very much, really. The hyphenation, if we want to call it that, was more evident in England than in India, and the better part of Zohra’s career as an actor was in the former. But yes, her success in England did mean she got noticed in India, especially after she came back for good in 1987.

GH: Zohra had progressive views, and lived an unconventional life. She worked and lived among the politically committed in her IPTA days, for instance. But her politics remain a little cloudy in the book — did she ever take an interest in using her voice, as an actress or a woman or a citizen, for political causes, whether in India or the UK?

RM: Zohra’s stint with IPTA was quite short-lived, and in fact when P.C. Joshi asked her to take charge of the Party’s Cultural Squad, she declined, saying she was an actor, not an activist. As far as I’m aware she was fairly apolitical. I wasn’t able to find much evidence of her being politically engaged when, for instance, there was a great churning in England in the 1960s, ‘70s, ‘80s. She was there, but distant from it all. Actually, of all the siblings, it was Hajrah, Zohra’s older sister, who was explicitly political, as a Communist. In Zohra’s case, I think the one political decision she took was to opt for India, not Pakistan, post-Independence. She and Hajrah stayed back, the others all eventually moved to Pakistan.

GH: The book resonates, as does Zohra’s life, with larger-than-life women and men with ideas, talent, and achievement. Who among these, other than Uday Shankar and Prithviraj, influenced her and gave her a sense of ‘belonging’?

RM: Her formative influences were Shankar and Kapoor. She greatly admired and respected the professionalism she found in theatre, film and television in England, so more than individuals, I think the dedication and seriousness of purpose she encountered there were important influences.

GH: You have now written two biographies, each of an outstanding woman artist. You refer eloquently, in your Preface to Zohra!, to the difficulty of separating the dancer from the dance. Your challenge is to ‘see the face behind the mask’. Would you tell us more about this challenge, and your strategies to meet it? And, because we tend to get quite a few hagiographies in India, how do you keep a biography from becoming one?

RM: We’re new to biography as a genre here, so whatever I say is tentative, especially as I’m trying something even newer — feminist biography. What does this entail? How should I approach my subject? How much should I reveal, and how much of her life should remain private? How much detail should I go into?

You speak about strategies, I ask: what are my responsibilities as a feminist biographer? In Zohra’s case the two main problems I encountered were: her celebrity status, and the fact that she had already written and published her memoirs. How was I to navigate both facts? Then, she was no longer alive, so I could neither verify anything nor probe more deeply.

I decided that I would “ignore” her celebrity status for the time being, see her as a woman in her times, locate her firmly in her context, in order to highlight what for me were the important questions. What were the circumstances in which she arrived at her decisions, made her choices? For example, if Partition hadn’t taken place, would she have made her career as a dance teacher, her original ambition, and her one “regret”. And so on.

The second was to try and see her through other people’s eyes: colleagues, other professionals, family, friends. Wherever possible. And then, as with Nayantara, never to speculate. One must, as a biographer, be sympathetic to one’s subjects, but one cannot be overawed by them. They’re human, after all.