Earlier this month in a petition challenging constitutional validity of the law of sedition, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the matter and issued a notice to the Centre. The petition, filed by army veteran S. G. Vombatkere, contends that Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) is wholly unconstitutional. Currently, there are several other petitions in the Supreme Court that have questioned the validity of the Section.

Editor of the newspaper Shillong Times, Patricia Mukhim, along with the Editor of Kashmir Times, Anuradha Bhasin, filed another petition contending the validity of the law. In their petitions, they state that the language used in this section is incapable of being defined with sufficient definiteness. In another challenge to the law of sedition, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court agreed to examine the constitutionality of the section and sought a response from the Centre for the same.

Last month, the Supreme Court’s decision in the sedition case against journalist Vinod Dua was widely appreciated. In its decision, the Court guaranteed every journalist protection under the Kedar Nath Singh (1962) case. It also stated that every prosecution under Section 124 A of Indian Penal Code should meet the standard laid down in the Kedar Nath Singh case, which makes violence or incitement to violence as necessary for the offence of sedition.

While hearing the petition filed by S.G. Vombatkere, the Chief Justice of India (CJI), Justice N. V. Ramana criticised the existence of a law on sedition and questioned its colonial origins. He pointed out that the law of sedition was used during the colonial period against freedom fighters such as Mahatma Gandhi and asked if such a law was still required to exist.

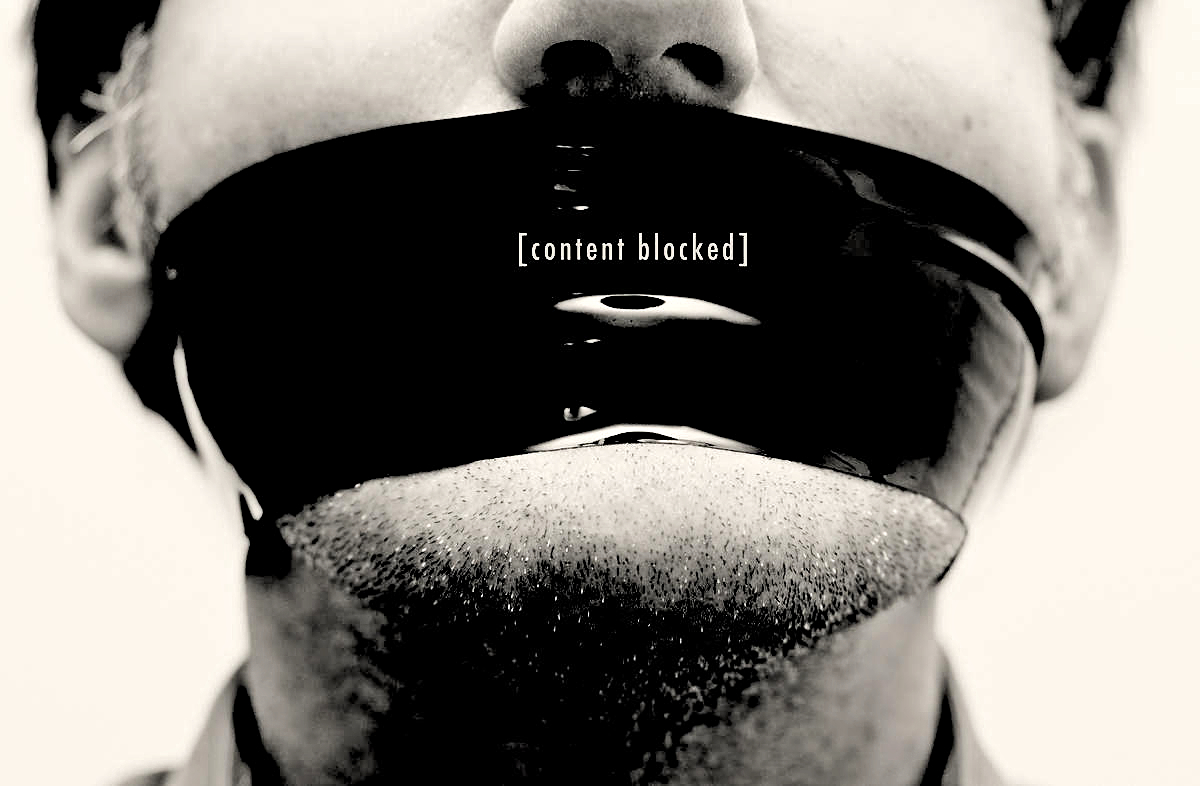

The Supreme Court’s willingness to examine the constitutionality of the law and the comments of the CJI become more significant in the larger backdrop of the increase in the number of sedition cases in recent years, coupled with the rampant misuse of the power by the executive while dealing with sedition cases.

Rising cases

From at least two sources, the data suggests that the number of sedition cases have been on the rise for the last few years. This should not come as a surprise, given that sedition charges have been the instant response against any kind of dissent — be it against the CAA protests or mismanagement of the Covid-19 crisis — of the government. Data shows that between 2016 to 2018, the number of sedition cases in India doubled. While the number of sedition cases keep increasing, the conviction rate under this law is very low. Between 2016 to 2018, there were only four convictions. A database maintained by Article 14 on sedition cases between 2010 to 2020 shows an increase in sedition cases since 2014, when the Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party government came to power. It states that out of 11, 000 individuals implicated under sedition from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2020, 65% were implicated after 2014.

It is not simply the increase in the number of cases filed that is an issue of concern with regards to sedition cases. The Section 124 A of Indian Penal Code is classified as a “non-bailable” and “cognisable” offence, which places wide powers in the hands of the law enforcement officials while dealing with matters under this section. The misuse of these powers without due consideration to procedural safeguards and the rights of the accused becomes a more imminent threat. In a detailed analysis of the sedition cases in the state of Karnataka on Article 14 , Mohit Rao states that “Karnataka ranks first in India by number of people against whom sedition cases have been filed for sharing content or making commentary on social media.” The article further states that such “cases have resulted in loss of jobs, accumulation of debt and isolation of accused, in particular, Muslims.” In a particular case that has been described in detail in the article, a person called Junaid was arrested for sharing an image of soldiers that was captioned as “I stand with Pakistan Army,” in the aftermath of the Pulwama attack. The caption was in English. Junaid could not read English and shared the image, mistakenly, as a support to the Indian Army.

Junaid ended up spending four months and 10 days in custody, his shop was burned down, and the village branded him a traitor. In the month of February this year, when the Delhi Police arrested climate activist Disha Ravi from her house in Bangalore, there was a complete violation of procedural laws regarding arrest. Rather than producing her before the nearest magistrate, she was brought directly to New Delhi and produced before a magistrate there without access to proper legal counsel. These cases illustrate how the law of sedition is susceptible to misuse and, hence, can lead to serious violation of fundamental rights.

The Article 14 investigation on sedition cases in Karnataka also highlights that even as there was a spike in sedition cases in Karnataka, the state was governed by a Congress government for a large portion of time from 2014-2021. This also makes it clear that sedition is a preferred tool to suppress dissent for any political party that is in power. In an article on The Leaftlet last month, senior advocate Mihir Desai argues that only the Supreme Court can do away with this law. The law provides political benefits to any political party and, therefore, the parliament will never do it.

Abolished in England

The law of sedition, which was introduced in India by the British colonial government, has been repealed in England. The Law Commission in Britain had recommended the abolition of the country’s sedition law in 1977, and the recommendation was carried out in 2009. At the time, one of the reasons given for its removal was the misuse of this colonial-era law in several of the Commonwealth countries. More than 70 years after Independence, the law still continues in India’s statute books and continues to be misused for suppressing dissent.

In recent years, at least two constitutional challenges to sedition have been rejected by the Supreme Court. In February this year, the Supreme Court rejected a petition filed by a group of lawyers against the law of sedition stating that no concrete case was brought before it. In 2016, a plea by Common Cause that sought for certification of incitement to violence by the director general of police and by the magistrate before arrest was also rejected. It is in this backdrop that the the apex court’s response to recent challenges to sedition law becomes more important.