Thinking about writing this was, for the most part, thinking about what the piece itself is and not so much about its content. My central question is about where the ‘criticality’ of this piece comes from, and if it does come through at all amid this balancing-act I found myself playing. The kind of critique that will follow is neither objective or intellectual-ly sound by any measure. Instead, it lies somewhere in the very inability to do anything but to think out loud. I feel free-er in some sense to talk about super-structures, governments and institutions that lie ensconced at a distance that is safely far from me. To be critical in this context – of the Krishnamurti schools – is somewhat troublesome, for the thinking aloud is at loggerheads at every moment with my deep entwinement with the institution, with my own being that was constructed with the nurturance that I picked up from this space.

In her beautiful foreword to a collection of essays titled Feel Free, Zadie Smith writes, “Essays about one person’s affirmative experience have, by their nature, not a leg to stand on. All they have is their freedom.” My anxiety in writing this appeared almost identical to hers, but hid in it quite the reverse — the fear is that my intimacy with the institution might turn a systemic issue into my one-person observation. It is not that I write like Smith does to say: “I feel this, do you? I am struck by this, are you?,” but that the limits of my own self, the boundaries of the personal are almost entirely unclear and exist in a flux with that of the institution. The freedom for this essay then, must come — if at all it does — from interrogating relentlessly the limits of the personal-self and singular observation to locate casteism as deeply permeating the spaces of the Krishnamurti schools.

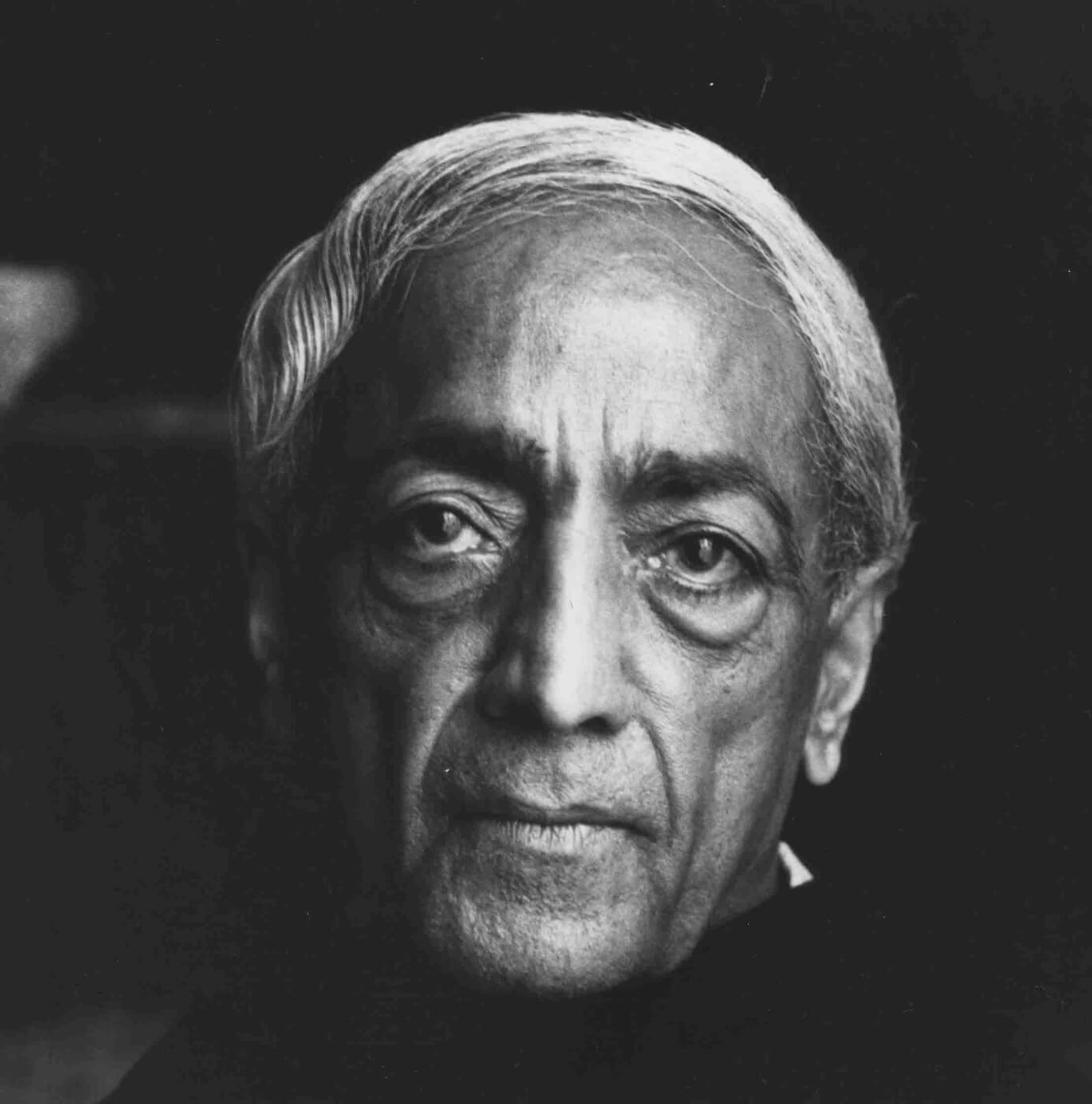

The “Krishnamurti schools” in India are “alternative” schools that were established by the thinker-philosopher J. Krishnamurti (1895-1986), and are run by the Krishnamurti Foundation of India (KFI). Besides these are also a few other alternative-schools with Krishnamurti’s teachings at the core of their pedagogy across the country.

“And is it not possible for all of us, while we are young, to be in an environment where there is no fear but rather an atmosphere of freedom; freedom not just to do what we like but to understand the whole process of living? Life is really very beautiful, it is not this ugly thing that we have made of it, and you can appreciate its richness, its depth, its extraordinary loveliness only when you revolt against everything – against organized religion, against tradition, against the present rotten society – so that you as a human being find out for yourself what is true. Not to imitate but to discover. That is education.”

— J Krishnamurti, Think on These Things (1964)

The schools are supposed to be (and I do believe they were/are) conceived and established out of love and a deep feeling for “a fundamental transformation in this destructive society”. However, it’s unfortunately this “love” that both holds us (students, former students, teachers) to the place fondly and traps us from ever being fully cognisant of the problems and subconscious casteism here.

The overt casteist practices of elitist mainstream schools all over India and the Brahmanism particular to them are well spoken about. The schools make no pretense about it either — several of these schools are in fact founded upon ideas of brahmanical supremacy and dominance. I cannot help but think immediately of the love and sense of reflection that my school experience gave me in the context of mainstream schools unleashing violence, casteism and religious fundamentalism upon their students. But it is all too easy to make me feel loved, equal and safe from the violence of this world; it is all too easy to make the predominantly brahmin-savarna students like me who inhabit the Krishnamurti schools feel love in the face of the world’s devastations, while also perpetuating a much subtler, quieter form of the same evil that is casteism in the processes shared with them.

I am trying to think back now at how often I must have heard the word “caste” mentioned at my school and whether I did at all. I remember — after much beating away at memory — that it must have been brought up twice, maybe thrice in a period spanning over six years:

The first (and perhaps a few more times after) was as a matter of requirement — when intermediate history lessons and textbooks spoke of the ‘Aryan Invasion’, the four varnas, the pre-vedic/vedic times and also made an almost half-hearted brush with questions of untouchability and Ambedkar, who was spoken about only as “the chief architect of India’s Constitution”.

Finally, we heard of caste again as high-school students preparing to visit rural Rajasthan in order to “understand the complexities of the country”. And here, caste was a monstrous evil — a monstrous evil of rural India nonetheless — where untouchability was still practiced and cost people their livelihoods and lives even.

To my mind, this absence of caste and conversations around caste is not in any way incongruent to the dominant schooling experience in the country. The incongruence is with the importance the Krishnamurti schools place on conversation, on dialogue, understanding our own positions and the spaces we navigate, and most importantly on trying to talk to students about systemic inequalities — of class, gender, race, sexuality, but never of caste.

The fact that the body of “teaching-staff” is primarily savarna elite needs close examination.

The fact that the body of “teaching-staff” is primarily savarna elite needs close examination. The staff that run the school are broadly divided by a stark marker that places them as teaching and so-called “non- teaching” staff. That the majority of the bahujan staff are called “non-teaching” — even when they do teach students weaving, carpentry or cook everyday meals in the kitchen — and that even many of their names remained mostly unknown to students (the schools are very small spaces where one would boast of everybody knowing each other) is a telling testament. The hierarchies of “skilled” and “unskilled” labour and the invisibilisation of bahujan labour within a caste-society are reproduced in a school that is meant to hold closely the teachings of J. Krishnamurti who spoke in his lifetime at length about livelihoods, ambition, the vile play of power.

One of the places where caste plays out in the most obvious senses is in food culture and eating together. In Krishnamurti schools across the country, students eat meals cooked at school together. These meals are entirely vegetarian (and egg-free in most cases). For the longest time as a student, I justified this to myself and others as a matter of “violence”, but this conception of violence is no more than a brahmanical myth, functions as code for purity politics, and a hegemonic control of food-practices of dalit, bahujan, adivasi and Muslim peoples. In the schools too, the question of meals being vegetarian is never up for examination, and Krishnamurti’s “principles” around violence seem to justify this unquestioning acceptance.

Krishnamurti has spoken about the consumption of meat in the same breath as violence, and has suggested on several occasions that the killing of animals/consumption of meat is “unnecessary” or concerning “the whole question of cruelty, compassion.” I do think, however, that Krishnamurti’s own position on meat needs to be critically placed within the context of his own brahmin background and Theosophical Society upbringing — to examine this is to consider the possibility that his position was inherited from a casteist ecosystem and acknowledge that he too was not somehow magically free of caste or casteless. Further, if Krishnamurti’s talks and writings on this matter are themselves looked into closely, he points quite precisely to the hypocrisy of vegetarians in wanting to dissociate from meat:

“Is that really a very great problem, whether we should have an egg or not? Perhaps most of you are concerned with non-killing. What is really the crux of the matter, is it not? Perhaps most of you eat meat or fish. You avoid killing by going to a butcher, or you put the blame on the killer, the butcher – that is only dodging the problem. If you like to eat eggs, you may get infertile eggs to avoid killing. But this is a very superficial question – the problem is much deeper. You don’t want to kill animals for your stomach, but you do not mind supporting governments that are organized to kill.”

— J. Krishnamurti, 3rd Public Talk, Colombo, Ceylon(¹), 1950

In saying this, I am not suggesting immediately that including meat and eggs in the diet is somehow the solution. The suspicion however, is that the non-examination of this vegetarian diet, while it might be rationalised as “non-violence” or “Krishnamurti school principles” holds beneath it several notions held by teachers, students and parents that have to do with purity, pride in vegetarianism, discomfort or disgust with meat or those who eat meat, and what Prof. Suryakanth Waghmore points to: “…vegetarians in India prefer social distance from non-vegetarians”². He goes on to say: “How fragile must the morals of the vegetarian castes be if they feel threatened by the introduction of eggs for poor children in schools? The morals of Indian vegetarians continue to be based less on compassion for humans and animals, and more driven by ideas of hierarchy and purity…”. ²

It is this fragility of savarna students and teachers that is preserved in the dietary decisions that the schools hold as almost sanctimonious. The handbook of Rishi Valley School, a boarding school even goes so far as to say that “STRICT ACTION WILL BE TAKEN”³ against parents even if they bring “non-vegetarian food items” while visiting their children. This likening of meat-consumption with a serious “disciplinary violation” seems to be a common thread across all the KFI boarding schools.

I know first-hand of an instance when my peers, who were on an informal trek organised by the school were not just reprimanded, but also vehemently shamed, accused and othered for eating meat (which they had bought from their personal monies on the trip). One person who was at the receiving end of this shaming told me that even as they went to buy themselves “non-vegetarian” food, she and the others knew that it would have to be done covertly not just for fear of being “caught” in the act, but also because they had internalised the school’s vegetarianism so much that they did not wish for their own eating of meat to offend the comforts of the vegetarian-brahmin co-travellers.

Even besides the fact of vegetarianism, meals are designed to cater to a brahmin sensibility and taste.

In a Krishnamurti school that is supposed to be built on a philosophy that is fundamentally free of rewards and punishment, the thwarting and shaming of young students for consuming the food of their choice can only be attributed to the interest of savarna teachers to preserve and further their own position of “purity” by ascribing shame, impurity, guilt and repulsiveness onto the bodies of these students.

Even besides the fact of vegetarianism, meals are designed (by a group of “teaching staff” and not those who actually cook the meals) to cater to a brahmin sensibility and taste. A visitor at one such school on asking a teacher why garlic, onion and even spice were used in such stringent measures was told that the children needed to eat “sattvic food”. The K school in Chennai, for example, serves curd-rice every day as a staple in the meal; the amount of onion and garlic used in the food are regulated to ensure that it is not “too much” etc. These decisions are of course unspoken or unwritten, and made covertly, but guided very deeply by what “right” food must be — “sattvic”.

References

https://www.dalitcamera.com/caste-food-ideological-imposition/

¹http://www.krishnamurtiaustralia.org/articles/vegetarian.htm

²https://scroll.in/article/833178/vegetarianism-in-india-has-more-to-do-with-caste-hierarchy-than-love-for-animals

³ Rishi Valley School Handbook: Life at School, A Handbook for Parents, Students and Staff