This is part II of the two part series on the impossibility of appropriating Dinkar and Benipuri by Anukriti Gupta. The part I can be read here.

The first part of ‘Hindu Right, Hindi and the Impossibility of Appropriating Dinkar and Benipuri’ discusses the myriad ways in which the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Sangh Pariwar constantly invoke and appropriate Ramdhari Singh Dinkar and Rambriksh Benipuri. It’s important to discuss why these stalwarts of Hindi literature cannot be easily appropriated and why the saffronisation of their writings will always remain an unfulfilled dream of the Hindu Right. Locating Dinkar and Benipuri in the freedom movement and the early years of the socialist movement in India can be one of the ways of questioning their saffronisation; another way can be to contextualise their writings and what they thought about the Sangh’s idea of imposing Hindi for the creation of a Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan.

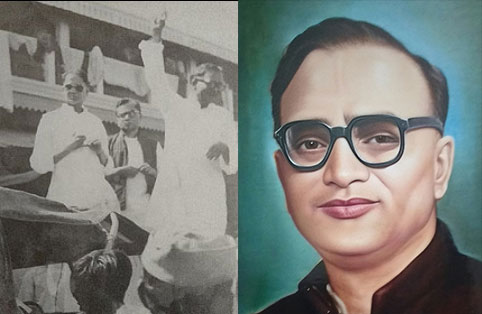

Why Dinkar and Benipuri Cannot be Saffronised

The birth of India’s socialist movement can be traced back to the early 1920s. Several Indian revolutionaries and freedom fighters travelled to Moscow during this period. Jawaharlal Nehru, the rising star of the Congress then, visited the Soviet Union in 1927 on the 10th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. During this time, the first generation of Indian communists struggled and paved the way for the subsequent formation of the organised socialist movement. The freedom fighters of Bihar were deeply influenced by the socialist thought. Those who were incarcerated for participating in the Civil Disobedience Movement in the early 1930s carried socialist literature along with them to jails. Soon, discussions about forming a socialist party within the Congress started floating around. The Congress Socialist Party was founded in 1934 in Patna by Jayprakash Narayan, Rambriksh Benipuri, Ram Manohar Lohiya and Acharya Narendra Dev. It was formed at the end of the Civil Disobedience Movement by those Congressmen who had come under the influence of, and accepted, Marxism and Socialism. Provisionally, it was decided that the objective of the party would be to work for a Socialist State which, among other things, would emancipate land and capital from individual and class ownership and vest it in the community, so that the advantage of the country’s resources might be equally shared by the members of the community. The membership was opened only to those who were members of the Congress and who were not members of any communal organisation. Its immediate programmes were disseminating Socialist ideas through pamphlets, public lectures and study circles and organising labourers and peasants. The first All India Congress Socialist Conference was held at the Anjuman Islamia Hall, Patna, on May 17, 1934. Benipuri was the driving force behind the formation of the Congress Socialist Party.

As a freedom fighter, he went to jail fourteen times and spent seven years of his life in jail; quite often for his revolutionary journalism.

Yuvak, an illustrated Hindi monthly magazine launched in 1929 by Benipuri promoted the ultimate goal of Swaraj for India by overthrowing the British regime. Its writings were clearly impacted by Marxism. Yuvak was edited, printed and published by Rambriksh Benipuri from the Patna Yuvak Ashram. The working-committee of Congress Socialist Party formed the Jansahitya Sangh to share its ideas with the common masses. Jansahitya Sangh’s revolutionary magazine Janata was first published in 1937; it soon became the mouthpiece against British atrocities and it raised the demands and issues of peasants and workers of Bihar. Benipuri was Janata’s first editor. At the 50th session of the All-India Congress Committee held at Faizpur in 1937, he moved a resolution to abolish the Zamindari system. He became the President of the Bihar Provincial Kisan Sabha in 1940. Benipuri was jailed several times between 1941-1942 for organising peasant agitations in Bihar. As a freedom fighter, he went to jail fourteen times and spent seven years of his life in jail; quite often for his revolutionary journalism. Patiton Ke Desh Mein, Chita Ke Phool, Lal Taara, Gehun aur Gulaab, Maati Ki Mooratein are some of his major literary works. Benipuri translated The Communist Manifesto in Hindi and wrote the biographies of Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg. Roos Ki Kranti and Laal Cheen are some of his other literary works which throw light on the influence of Marxism and Socialism in his writings. Benipuri’s Rosa Luxemburg: Sansar Ki Shresthtam Samajwadi Mahila is one of the first biographical works on Luxemburg written in Hindi.

First published in 1938, Rambriksh Benipuri’s Lal Taara marks the arrival of socialist thought in Hindi Literature. Benipuri writes in the preface of Lal Taara1,

“Lal Taara mere shabdchitron ka pehla sangrah hai. Iska pehla roop us zamane mein nikla tha, jab main sar se pair tak lal-lal tha. ‘Lal Taara’ ek naye prabhat ka prateek tha. Woh prabhat ab adhik sannikat hai. Shayad isiliye andhkaar bhi adhik saghan ho chala hai.”

In Benipuri’s short story Hansiya Aur Hathora2, Hammer and Sickle are siblings. As symbols of the industrial worker and the peasant and as the emblem of the former Soviet Union and of international communism, Hammer and Sickle put forward an interesting conversation in the story which concludes with the decision to march on;

“Dono badh rahe the ~

‘Duniya ko dikha dungi, main sanchay ki hi devi nahi, sanhar ki dhatri bhi hoon.

‘Nirman ka karya humse khoob liya gaya, duniya ab zara hamara prahar bhi dekhe!’

‘Badhe chalo, bhaiya!’

‘Haanth bantao, bahini!’

The significant change which came with the formation of socialist groups in the 1930s impacted the writings of Hindi scholars. Hindi literature focused more and more on the sociological and economic impacts of British imperialism. Socialist writers and artists came together to form the ‘Nav Sanskriti Sangh’ in the Kanpur session of the Akhil Bharatiya Socialist Party with Rambriksh Benipuri heading its working committee. The Progressive Writers’ Association which came into existence in 1936 drew more and more Hindi writers influenced by the Socialist, Marxist, Communist and Trade Union movements of the time to its fold. All these movements were gaining ground by raising their voice against social injustice, economic disparity and the exploitation of the poor, the peasant and the labourer. Fiction writers like Yashpal, Pratapnarayan Srivastava, Bhagwaticharan Varma, Rahul Sankrityayan, Rangeya Raghav, Ramchandra Tewari and poets like Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Sumitranandan Pant, Suryakant Tripathi Nirala, Bharat Bhushan Agrawal, Rameshwar Shukla Anchal and Kedarnath Agarwal were moved by Marxist and socialist thought and leftist influence is strongly apparent in their writings.

Dinkar’s idea of freedom is not only political; it is social, cultural and economic at the same time.

In his poem ‘Van Phoolon ki Or’, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar portrays a vivid picture of economic exploitation; focusing on the exploitation of the peasants in the hands of the capitalists. In his epic poem, ‘Kurukshetra’, Dinkar argues that equal means and opportunities for development should be available to both the rich and the poor and without the equal distribution of wealth, there would be no end to unrest. Poverty, hunger, illiteracy and exploitation of the working class are some of the recurring themes in his poems. In another poem ‘Dilli’, Dinkar records the sighs and cries of the struggling masses in the city and asserts that Delhi is built upon the blood and the bones of the poor. Dinkar’s idea of freedom is not only political; it is social, cultural and economic at the same time. His poems unveil the cruel reality of the imperial and feudal exploitations in colonised India. He criticises both British colonialism and the feudalism existing in the Indian society at the same time. In the preface of Rashmi Lok: ‘Reṇuka’ se ‘Hare ko Harinam’ Tak ki Pratinidhi Kavitaen, a compiled edition of his works, published in 1974, Dinkar throws light on his ideological moorings and inspirations and the major themes of his poetry,

“Jis tarah main jawani-bhar Iqbal aur Rabindra ke beech jhatke khate raha, usi prakar main jeevan bhar Gandhi aur Marx ke beech jhatke khata raha hoon. Isiliye ujle ko lal se guna karne par jo rang banta hai wahi rang meri kavita ka rang hai. Mera vishwas hai ki antogatva yahi rang Bharatvarsh ke vyaktitva ka bhi hoga.”3

Dinkar kept swinging like a pendulum between Karl Marx and Gandhi. As he writes, red and white were the colours of his poetry. The attempt to look for the colour saffron in his writings is yet another failed attempt of appropriation by the Hindu Right in contemporary India.

Dinkar’s poetry invokes both “veer and shringar ras”, it does not promote the idea of BJP’s India. Dinkar’s poetry is characterised by aggressive posturing and contains appeals of being chivalrous and demanding strength to defend the nation. These elements are attractive to the BJP. However, many of these poems are located in India’s freedom struggle and invoke nationalism, strength and chivalry to fight against colonialism and feudalism. One of Dinkar’s seminal works, Sanskriti Ke Char Adhyaya, which won Sahitya Akademi award in 1959, draws its historical framework largely from Jawaharlal Nehru’s The Discovery of India and is perhaps the only Hindi book whose preface the first Prime Minister of India wrote. Even though Dinkar was thrice elected to the Rajya Sabha as a Congress nominee from Bihar, he did not submit to the political ideology of the Congress entirely. In his ‘Bharat Ka Yeh Reshmi Nagar’, he describes the capital city as a place where the children of the poor are worse off than the pets of the rich rolling in extreme wealth. He describes the insensitivity and cruelty of the capital city towards the woes of the poor and marginalised.

BJP’s Hindi Imposition and Hindi Litterateurs

It is rare to find a Congress leader making use of Dinkar’s poems today, even though he remained with Congress for a long time. It is ironic that the BJP has organised several functions in Dinkar’s memory and has celebrated his birth anniversary in the recent past in various parts of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, majorly to garner the upper-caste votes in the Hindi belt and to emphasise upon the importance of ‘one language one nation’.

“Urdu played a very significant role in bringing Hindi literature closer to the masses. Hindi literature is deeply indebted to Urdu.”

Dinkar’s poetry makes substantial use of myths and epics, reinventing his messages around these works to evoke an aggressive form of nationalism, something which has been convenient and easy for the Hindu right-wing parties to appropriate and pitch against their ideological adversaries. If the RSS sees Hindi imposition as a way to achieve its goal of Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan agenda, for the BJP, it is a way to consolidate its strong vote base. The BJP’s support is the strongest among people who watch and read news in Hindi according to the National Election Study 2014 conducted by Lokniti CSDS. In that case, renowned Hindi writers and their work become easy tools for the Sangh Pariwar to popularise Hindi imposition. However, both Dinkar and Benipuri cannot be appropriated to popularise the Sangh’s ‘sanskritised’ version of Hindi. The founding members of the Congress Socialist Party such as Lohiya, Acharya Narendra Dev and Rambriksh Benipuri supported the evolution of a common language with a name new ‘Hindustani’ which according to them was essential for maintaining Hindu-Muslim unity. On the other hand, the Hindu Mahasabha in its Nagpur session of 1938 passed a resolution that ‘sanskritised’ Hindi and not Hindustani should be the National Language of India and that Sanskrit vocabulary rightly deserves to be the National Language and Devanagari the National Script of India. Dinkar writes about Benipuri’s idea of Hindi-Hindustani,

“Hindi-Hindustani-vivaad ke samay Benipuri ji Hindustani ke pakshpati rahe the. Jab Samvidhan ka Hindi anuvaad prakashit hua, Benipuri ji use dekhkar ghor nirasha mein doob gaye aur bole, ‘Dinkar, Hindi rashtrabhasha nahi hui. Rashtrabhasha to Sanskrit banayi ja rahi hai.”4

Dinkar’s approach towards Hindi is also not in tandem with the RSS’ idea of Hindi. In September, 1973, Dinkar while speaking in Bombay made some revealing observations about the evolution of his poetry and the importance of Urdu and Hindi,

“—In the pursuit of my poetic career, I studied Tagore and Iqbal and kept swinging like a pendulum between the two. Urdu played a very significant role in bringing Hindi literature closer to the masses. Hindi literature is deeply indebted to Urdu. Personally, I do not discriminate between Hindi and Urdu and am equally desirous of the development of both the languages.”5

At a time when historical narratives are being imagined, invented and popularised, it is significant now, more than ever, to historically and politically contextualise the poetry of Dinkar and the prose of Benipuri and many other Hindi writers and poets which are being seamlessly appropriated by the Hindu Right. It is also equally significant to understand that Hindi is not a homogenous language and it cannot become a tool for fulfilling the Sangh’s vision of Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan. It’s time to spell out the impossibilities of appropriation.

1. Benipuri, Rambriksh (1944). Lal Taara, Benipuri Prakashan.

2. Benipuri, Rambriksh (1944). “Hansiya Aur Hathora”, Lal Taara, Benipuri Prakashan, Page 19.

3. Dinkar, Ramdhari Singh (2011). Rashmi Lok: ‘Reṇuka’ se ‘Hare ko Harinam’ Tak ki Pratinidhi Kavitaen. Repro Books Limited.

4. Dinkar, Ramdhari Singh (1969). “Swargiya Benipuri Ji”, Nayi Dhara: Benipuri Smriti Ank, Page 190-191

5. Syed L. Husain (1976). Urdu: A Precious Heritage, Sahitya Akademi, Page 83