The recent release of Radhe (2021) faced a lot of criticism, not only for its storyline or the lack thereof, but also for its tone-deaf portrayal of the female protagonist. This essay focuses on Hindi Cinema, which is now popularly branded as Bollywood and its changing yet problematic representation of Indian women, arguing that portrayals of Indian women like those in films like Radhe is a result of the images constructed in Hindi films over the years.

Images are rather powerful instruments of constructing a specific notion, oftentimes rigid, with its prolonged usage. In this regard, cinema or the broader ambit of media plays an extensive and an important role in the construction of ideas of ethnicity, religion, culture, nationality. It furthers the constructions of the ideas of sex and gender, the representation of their roles and norms in the society to the viewers it is catering to. With globalisation, the propagation of content through films or cinema is at its fluid best. The transmission of content now moves beyond territorial boundaries, often facilitating, and at times even proselytising cultural exchanges.

It is interesting to trace the trajectories of portrayal of women in Hindi cinema, gradually transitioning into Bollywood. Birthing from the colonial embryo, excavating a reality which resonated with the Indian masses, articulation of the Indian culture which remained long suppressed under imperial modernity, was indeed a ponderous affair. Benegal opines that cinema often acts as a medium of providing an insight into human conditions, the greater reality through the art of articulate narratives. The managerial task during the birth of cinema in colonial India was the construction of the identity of the Indian nation. A nation encompassing its own people, its ethno-cultures, its shared historicity. The knowledge production through cinema was devoted to this realm. The works of Dadasaheb Phalke and Himanshu Rai as early as the 1920s, emphasised on the Swadeshi project, as a countervailing force to the project of colonialism; the “Indianness” to counter the imposed Europeanness, which often lost the plot in the oriental debate. In terms of representation of women, as Datta observes, the blueprint of the ideal woman, a village belle with Indian values, coupled with a tint of glamorisation of the West was witnessed.

Independent India saw the portrayal of women in a symbolic sense to construct a national identity, a national culture, namely in a film like that of Mehboob Khan’s Aurat , later remade as Mother India in 1956. The presentation of women for identification with the nation long oppressed is not an innocent representation if delved deep into. The semiology of a woman being invaded, suppressed and then saved by her children, as Datta notes, invariably portrays an image of vulnerability, lack of resilience and the incessant need to be protected (by the more powerful gender in this regard), thus shaping her identity in the minds of the viewers.

Through much of the ‘60s and ‘70s, gradually transitioning to the genre of romance and action, the role of women in cinema remained restricted to saree-clad romanticism in the woods, upholding of Indian values in the households, abduction, vulnerability and excessive protectorship from her male counterpart, coupled with sexual objectification in the form of cabre, borrowed from the West, which earlier used the premise of a king’s court, articulated through traditional Indian dance forms.

With the women’s movement gaining strength in India, a greater call for changing, rather diversifying the portrayal of women in Indian cinema gained momentum. With the simple narrative style of Satyajit Ray, and later, makers like Aparna Sen, Aruna Raje, Kalpana Lajmi, induced the context of women, their separate identities, journeys and ownership of self in the established spectrum of representation. However, most of it, often remained limited to the vernacular sphere, generally catering to a small number of viewers, with a larger number of audience unwilling to look beyond the rigid perception created by the prolonged misrepresentation, which they now considered knowledge. As Bhattacharjee observes, “consequently, anything that threatens to dilute this model of Indian womanhood constitutes a betrayal of all that it stands for: nation, religion, God, the Spirit of India, culture, tradition, family.” However, with the advent of satellite television in the ‘80s and its wave hitting the Indian platform in the 1990s, image production and its capitalisation replaced narrative cinema. There was greater dispersion, commodification and marketisation of cinema as a ripple effect of economic globalisation, also expediting cultural globalisation. There is a noticeably disturbing shift in representation of women in Indian cinema in the decade of the ‘90s and onwards, with its increasing Bollywoodisation. There could now be seen two types of objectification of women in the globalised setting: the established intactness of the ‘simple, Indian girl with Indian values’ and the ‘Western, urbanised girl clad in Western clothes’. The former was symbolic of untouched chastity while the latter was to be won over by the extravagant masculinity and wooing (eve-teasing) of the male protagonist. With reference to Yash Johar’s Duplicate (1998), Datta writes, “In one situation where the duplicates have switched roles, the gangster tries to seduce the heroine to the tune of a light hearted song, pulls her saree and gropes her. This form of retrogressive representation in a country where women are constantly battling against physical violation and sexual harassment, is seriously alarming as it trivialises real issues which affect women in their day to day lives. Here is an instance of a global (read western) image used with a ‘mis’ reading or ‘non’ reading of a cultural context.”

Nevertheless, filmmakers such as Mira Nair (namely in works like Fire, Kamasutra ) and Deepa Mehta along with Shyam Benegal (in works like Mammo) depicted, as Naficy opines, ‘journeys of identity’ of the Indian women, exploration of their sexuality, shifting from the realm of women as objects of atrocities to women with agency. However, such content which threatened the established norm of patriarchy faced innumerable obstacles in their path of propagation, often received as explicit content by the larger audience who were indoctrinated to accept women as mere objects of visual appeal. The decades of peripheral representation of women in the backdrop of a village was now replaced with the backdrop of an urban, cosmopolitan culture of ‘global India’. Moreover, as Sharpe notes, the symbolic identification of a woman with the nation remained unscathed, only tailored in a transnational setting, to cater to the escalating Indian diaspora.

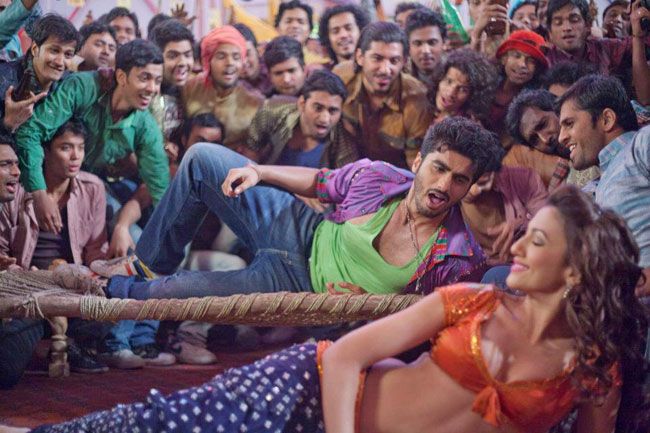

It is critically cardinal to highlight the fact that since the imitation of the ‘MTV Culture’, and the Bollywoodisation of Hindi cinema, the vogue of objectification has retained itself, through overpowering masculinity and through the rather glamorised form of ‘item numbers’ for the purpose of ‘innocent entertainment’ and avid commercialisation. Moreover, the voyeuristic imageries of rape often enhance the rigid sense of masculine-dominated culture which tends to increase crimes against women in an already volatile nation. In this context, Gopalan states, “films replete with avenging women, gangsters, brutal police force, vigilante closures stage some of the most volatile struggles over representations that shape our public and private fantasies of national, communal, regional and sexual identities.” The Hindi film industry is highly marketised, with extensive national and global reach. However, it has failed, for the most part, to break away from the parochial shackles and utilise its phenomenal reach for adequate and powerful representation of women. The shift, in the present times, to the narrow portrayal of women in the name of liberal feminism, with women wearing minimal clothes, smoking and drenching themselves in alcohol to fight the established patriarchy eschews the very idea of women with agency or the fight for it, often resulting in greater objectification.

One may argue that certain commercial Hindi films are indeed women centric, like Highway (2014), NH-10 (2015), Raazi (2018) or the newer additions in OTT platforms like Bulbbul (2020). However, such transitions are rather slow and whether they pass the ‘Bechdel Test’ remains a matter of debate. It is essential to bring this issue into gender discourse, with the usage of cinema as an instrument in facilitating change in the rigid minds of its large consumer base, especially in the wake of growing crimes against women, specifically in India.

References

-

Benegal, S. (2010). Talkies, Movies, Cinema. India International Centre Quarterly, 37 (1), 12-27.

-

Datta, S. (2000). Globalisation and Representations of Women in Indian Cinema. Social Scientist, 28 (3/4), 71-82.

-

Dasgupta, S. D. (1998). A Patchwork Shawl: Chronicles of South Asian Women in America, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

-

Gopalan, L. (1997). Avenging women in Indian cinema. Screen , 38 (1), 42-59.

-

Naficy, H. (2001). An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

-

Sharpe, J. (2005). Gender, Nation, and Globalization in Monsoon Wedding and Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. Meridians, 6 (1), 58-81.