Kalathilparambil Raman Gouri (KR Gouri: 1919-2021) was born into a tumultuous Kerala at the cusp of change, where a myriad streams of reconstruction, reform and renaissance were working towards sweeping transformations in many fundamental aspects of human life. As someone whose life and career can explain Kerala’s own growth and strenuous transition into a modernity, Gouri’s passing is widely considered as the end of an era. She was the last surviving member of Kerala’s first Communist ministry formed in 1957 and one of the most prominent contributors to what made Kerala what it is today. From there, she rose to high rungs of the party and party-led governments, even up till the doors of Chief Ministership, which was taken away from her due to varied reasons. All throughout her life, two of the most remarkable facets of Gouri’s persona were her free will and individual spirit. So crucial were these to Gouri’s being that it influenced the various decisions both she and the Communist party took for herself. In a way, Gouri’s political existence lay in the eternal conflict between the individual and collective, member and organisation, personal and political — some of the contradictions that have dogged many stalwarts in history. At the same time, the ebbs and flows in her political career are also testimony to the “enigma” of the Kerala woman, to borrow sociologist Swapna Mukhopadhyay’s term. A high performer in conventional social development indices, the Malayali woman still falls behind in terms of actual empowerment — her low public and political participation being a reflection of this. While a product of all liberative qualities of Kerala’s renaissance and subsequent modernity project, Gouri’s life therefore, is emblematic of its own inconsistencies, unevenness and contradictions.

Gouri’s father, Kalathilparambil Raman, was an Ezhava aristocrat from Alappuzha in north Travancore and an active member of the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (SNDP), the organisation co-founded in early 20th century by Sree Narayana Guru and played a pivotal role in Kerala renaissance. Although a backward caste, the Ezhavas were an economically ascending class. Gouri was born into the crucible of all this. During the struggle for temple entry at Vaikom (1924-25), at the helm of which was the SNDP, Raman was imprisoned multiple times for his involvement. Raman is also said to have donated acres of land and huge sums of money for the movement. In a home where Guru himself and SNDP’s TK Madhavan were frequent visitors, political participation was an everyday affair. A keen observer of the socio-political developments around him, Raman and his wife Arumuriparambil Parvathiyamma named the seventh of their ten children after Gouri Sankunni, one of the earliest Malayali women post graduates and an officer at the Madras Government Service. Gouri received the best education available in Travancore at the time and excelled throughout her academic life, thanks to her progressive family. She was the first person to pass tenth standard and the first woman to receive a Bachelor’s degree in her family. She also went on to become a gold medallist from the University of Madras and then Kerala’s first Ezhava female law graduate.

As a young adult, Gouri was influenced by the politics of her father and Communist brother KR Sukumaran. The native kingdom of Travancore during the 1940s, was witness to a mix of armed and unarmed anti-imperialist and anti-royalty movements, with the Communists and Socialists playing an extremely crucial role in all of this. Alappuzha was the epicentre of all this, thanks to its large peasant and working class population. Alongside not meeting the demands of the people, their attempts at protest were brutally suppressed by the royal state that ruled Travancore. Gouri was thrown into the vortex of anti-imperialist, anti-royalty resistance movements as well as multiple peasant revolts — culminating in the legendary Punnappra Vayalar uprising. A bright student, she travelled to Cochin and Trivandrum to further her studies. These were centres of political unrest and resistance at the time in Kerala and soon, Gouri was drawn towards the burgeoning Quit India Movement (1942) as a student union leader. “I was at the forefront of organising girl students. I’d go to every hostel and ask them to not go to class and join us for political demonstrations in the city”, she said in a 1992 radio interview. From there, she increasingly began participating in anti-British efforts as a student organiser, mainly representing the Left-wingers within the Indian National Congress. During the armed Punnappra-Vayalar uprising (1946), led by Alappuzha’s Communists against the princely state and especially its Diwan, Sir CP. Ramaswamy Iyer, Gouri’s brother Sukumaran went briefly missing, along with many Communists and Socialists of the time against whom the state had unleashed brutal police repression. Thousands of men and women Communists were murdered, many imprisoned on cooked-up charges and the rest had gone into hiding. During this volatile episode — which Gouri has called a “period of state terrorism” — her family had also opened their home to Communists who sought refuge. To demand justice for the protestors, including her brother, she took to the streets for the first time as a participant in demonstrations. When Sir CP Ramaswamy Iyer declared that Travancore will not join the Indian union, socialists and communists like her were at the forefront protesting it. As part of it, on August 15th 1947, Gouri was among the two who had organised a flag hoisting ceremony at a post office in Cherthala. “That’s what was unique about that time. All those who desired freedom were out on the streets,” she says.

Like Godavari Parulekar, Kalpana Dutta, Hajrah Begum, Ahilya Rangnekar and many others, Gouri’s life has to be read and celebrated alongside the many women who spent a lifetime fighting to build the Indian Communist movement. At the same time, there are few female Communists in India who have had a political life as dynamic and spirited as Gouri did.

As a young lawyer in Trivandrum and Cherthala she was also a member of socialist political formations leading hundreds into many struggles against the state. Like Gouri herself has said multiple times, due to her active role in the region’s political scene, she was not unknown to prominent Kerala Communists of the time. Gouri’s first tryst with Communist organisational activity was as part of a committee that organised the event of AK Gopalan in Kochi, she says in a TV interview. Soon after that, as a lawyer at Cherthala’s Magistrate Court, she took up the cases of local Communists and gained knowledge regarding property and land rights and policies of the region. This was the experience that aided her at a later stage when she piloted some landmark ordinances regarding land distribution for the marginalised. In 1948, it was P. Krishna Pillai, one of the founders of the Communist movement in Kerala, who gave a 20-something Gouri the CPI membership and nominated as a candidate for the first Travancore Assembly Elections that took place after the declaration of universal adult franchise. However, the Communists lost the election and in 1948, the CPI was subjected to a national ban, and as a result, in Kerala, its leaders were both subjected to brutal police violence and had to go into hiding. Gouri too was arrested for speaking against the police, and the violence she faced in custody is part of Kerala’s history. She says in an interview:

“I ran, hearing the screams from the prison wards of our male comrades, realising that they must be getting beaten up badly. I was stopped by Lakshmikuttiyamma (police officer), on whose hand I bit. But then came along a male police officer and that’s when it all began. Standing atop my stomach, they kicked me with their boots. But every time they hit me, I hit them back and bit them too. They hit me until I lost my consciousness. Once I woke up, I demanded that action be taken against the officers who hit me. I sat on a hunger strike in prison, without waiting for anybody. I was adamant. For they had insulted me.”

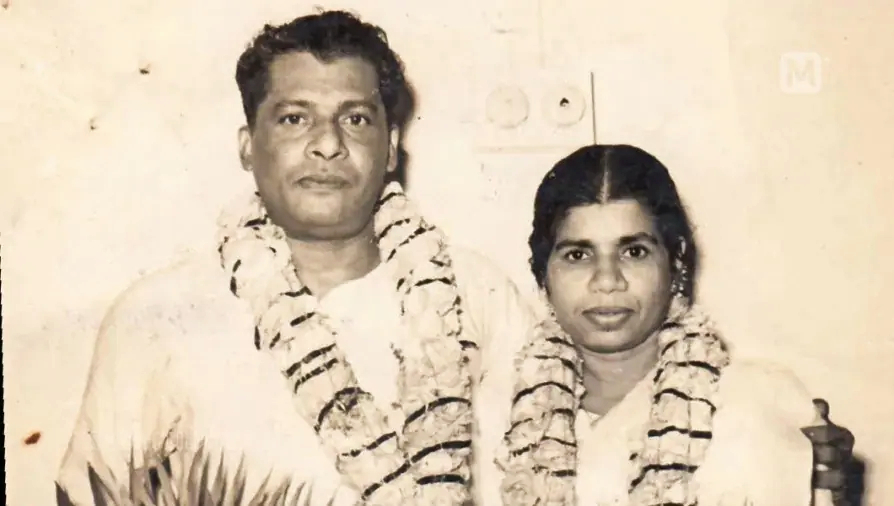

Interestingly, it was in one of these prisons that Gouri met and fell in love with T.V. Thomas, fellow Communist, whom she later married. She recalls how they threw little written notes across cells in secret, rolled up in stone. Two of the most revered leaders of the Communist movement in the state, the story of their love, marriage and eventual divorce remains one of the most discussed emotional issues in Kerala’s political history.

In the elections that took place in 1952 and 54 to the Travancore Council of Legislative Assembly, Gouri was elected by a big margin, although the rest of the Communists had to wait until 1957 to come into power.

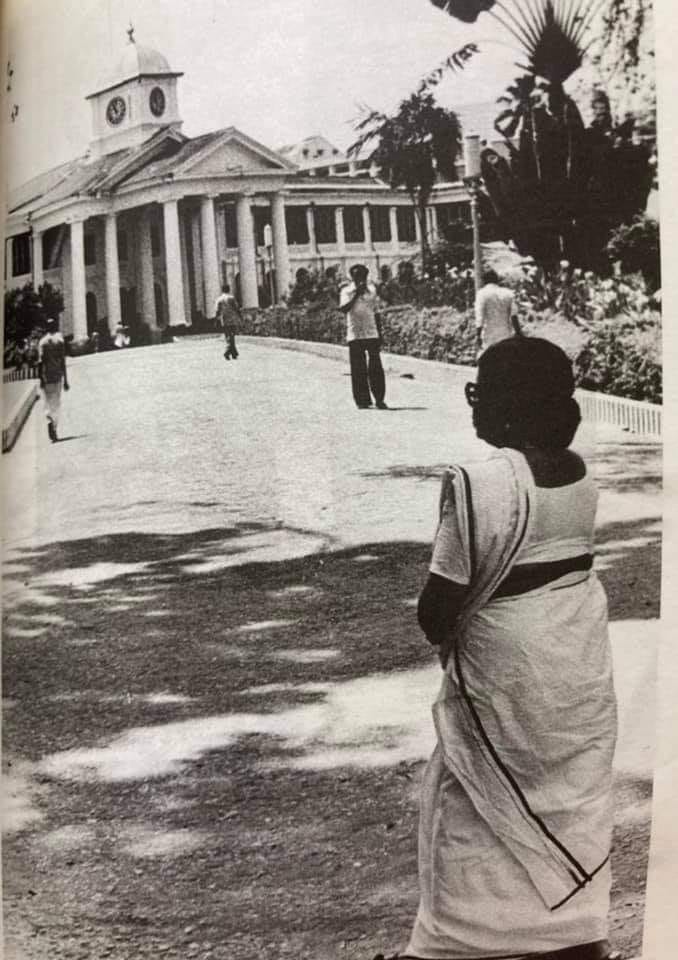

As mentioned above, with Gouri’s passing, Kerala has lost who was the last surviving member of the first democratically elected Communist government in India (second in the world), 1957. Elected to the Kerala Legislative Assembly in the region’s post-renaissance atmosphere, the new EMS-government consisted of members who had a history of active participation in the struggles that led to the making of Kerala’s modernity, including Gouri. As a result, the kind of reforms and legislation they brought in, which affected varied aspects of society like property rights and education, were a continuation of their efforts outside of the government. Gouri was the EMS cabinet’s Revenue, Excise and Devaswom Minister who formulated and presented two of the most radical legislations in Kerala’s post-Independence history, the Land Reforms Ordinance and the Agrarian Reforms Bill. In the backdrop of the Communist ministry’s slogan “land to the tillers”, these two banned the eviction of marginalised tenant-farmers from the land owned by their upper caste landlords, provided them with the right to claim ownership over the land on which they laboured and also fixed a cap over the amount of property a landlord could own. Gouri’s experience of having dealt with a myriad eviction and property cases as a lawyer was an asset to the cabinet, whose reforms triggered widespread socio-political changes in Kerala and are celebrated till date as having played a part in the making of its modernity. Gouri’s skills and efficiency as an administrator were celebrated and she went on to become a minister handling top portfolios in every Communist ministry till 1987 and in those that came after her split with the party as well — making her the longest serving woman minister in Kerala and one of the longest serving MLAs in independent India’s history. Every time, the firebrand activist excelled as an excellent administrator as well. Outside of parliamentary politics, Gouri was at the helm of various Communist Party-led associations — the President of the Kerala Karshaka Sangham (Kerala Farmers’ Association) from 1960 to 1984 and of the Kerala Mahila Sangham from 1967 to 1976. All of these made her career rather exceptional in the list of Indian women in politics.

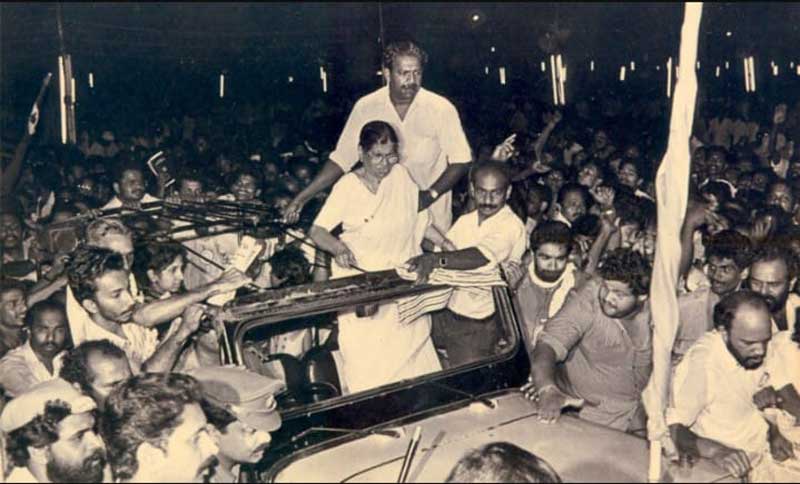

Though not officially declared by the CPI(M), Gouri was generally considered as the Chief Ministerial candidate by a majority of the Kerala public during the 1987 Assembly elections. Slogans that indicated the people’s desire to see her at the helm of the government reverberated across the state. However, to the great shock of the entire state, it was EK Nayanar who was chosen as the CM that year. The party was then criticised for having sidelined Gouri due to her gender and caste. Australian historian and Kerala expert Robin Jeffrey has called it a “tribute to Kerala’s patriarchy”.

It was Gouri’s will and fearlessness to voice her independent opinion throughout her political career that made her stand out from most Communist leaders Kerala has seen so far. And most importantly, she did so with no regret or second thought, and this was often seen as her personal ambition to grow beyond and outside the Party. In fact, her will to stay true to her own convictions and perspectives, was what made Gouri a force that couldn’t be contained by any socio-political institution — her caste, gender, marriage or even her own political party. Two of the most noted instances which exemplified her fierce independence were the breakdown of her marriage with T.V. Thomas (1910-77) and her expulsion from the CPI(M) in 1994.

In 1964, when the CPI split into CPI and CPI(M), Gouri’s then partner and fellow Communist from Alappuzha, T. V. Thomas stayed with the CPI and Gouri with the newly formed CPI(M). Gouri and Thomas, who fell in love in prison in the ‘40s, then ended up staying in adjacent ministerial residences. While initially there was a path that connected their official residences, Thomas’s “Rose House” and Gouri’s “Xanadu”, it was slowly shut as CPI-CPIM relations weakened — one of the most dramatic and emotional episodes in contemporary Kerala’s existence. Although Gouri admitted later on that the incident had hurt her deeply, it is still cited as an example of Gouri’s belief that the personal cannot be divorced from the political.

A number of organisational issues and conflicts finally led to her expulsion from the CPI(M) in 1994, when she defied its orders not to attend a committee formed by the Congress-led United Democratic Front (UDF) for the “development of Alappuzha”. The UDF had asked Gouri to chair the committee and CPI(M)’s argument was that it was their attempt to weaken their local body. However, Gouri refused to quit the committee and also kept away from the CPI(M) meetings that followed. Following her expulsion, Gouri formed the Janadhipathya Samrakshana Samithi (JSS), with a large Ezhava base, in Alappuzha, which then went on to join the UDF. In the elections that followed, Gouri won as a Congress ally, and from 2001-06, she was a UDF-minister from the JSS. In 2006, she contested again but was trounced by her former comrades in the CPI(M), which was repeated in 2011 too. From then on, she gradually started moving away from the UDF and towards the CPI(M). By then, the 97-year-old stalwart had withdrawn from public life, but from then on remained steadfastly with the Left.

Soon Gouri will turn into a pyre,

The fire in the pyre will dispel the dark,

As the pyre settles,

The cinder would remain,

The cinder would cool down

And turn into ashes,

To nourish the soil,

For fresh greens to sprout.

— From Balachandran Chullikkad’s poem “Gouri”, written post her expulsion in 1994.

Today, Kerala’s CPI(M)-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) government has come back to power with a huge, historic and unprecedented mandate. Yet, the most conspicuous absence is that of KK Shailaja, the health minister from the previous LDF cabinet who was internationally acclaimed for her skilful management of the COVID-19 crisis in Kerala. Shailaja, like all other two-time ministers, has been kept out of the government this time as part of the party’s new decision to have new faces at the helm. Like someone wrote on Facebook, however, “The fire in Gouri’s pyre has not settled as yet. A finger goes up in protest”.