Indian courts have for long acted as marriage bureaus in cases of sexual violence. The Supreme Court is not the first, and might not be the last.

The Chief Justice of India, SA Bobde, said earlier this month that his statement in court asking a rape accused whether he would marry the victim was completely misreported. During another hearing, he said that under Section 165 of the Indian Evidence Act, judges have the power to put questions or order production. Bobde’s remarks nevertheless raised a debate over the rights of survivors of sexual violence to make their own decisions regarding their future.

In judicial discourse, the rapist is either portrayed as atavistic, i.e., a male body that falls from culture, or as a pervert who needs medical attention. These sentiments, where the culture needs to change, echoed in the recent comments of Uttrakhand Chief Minister Tirat Singh Rawat, who criticised the ripped jeans trend. His remarks, too, invited countrywide condemnation through slogans like “torn jeans, visible knees, do not guard my thinking.”

In cases that come before courts, the survivors of sexual violence are portrayed as weak. Therefore, the legal definition of sexual violence needs to be invoked to remove the social stigma that such survivors face. To illustrate, in June 2015, the Madras High Court granted bail to a rape accused to mediate with the survivor. The bail order had referred to the survivor as “nobody’s wife” and “an unwed mother”.

Furthermore, the courts have delivered a deeply patriarchal understanding of Indian social structures. For example, in 1952, in Rameshwar vs the State of Rajasthan, the Supreme Court distinguished between rape victims in India and the western world by emphasising the social repercussions of rape for a woman in India. Similarly, in 2015, a judge in Odhisa ordered prison officials to organise the wedding of a woman and her alleged rapist after they filed a joint petition as the survivor had “no other option”.

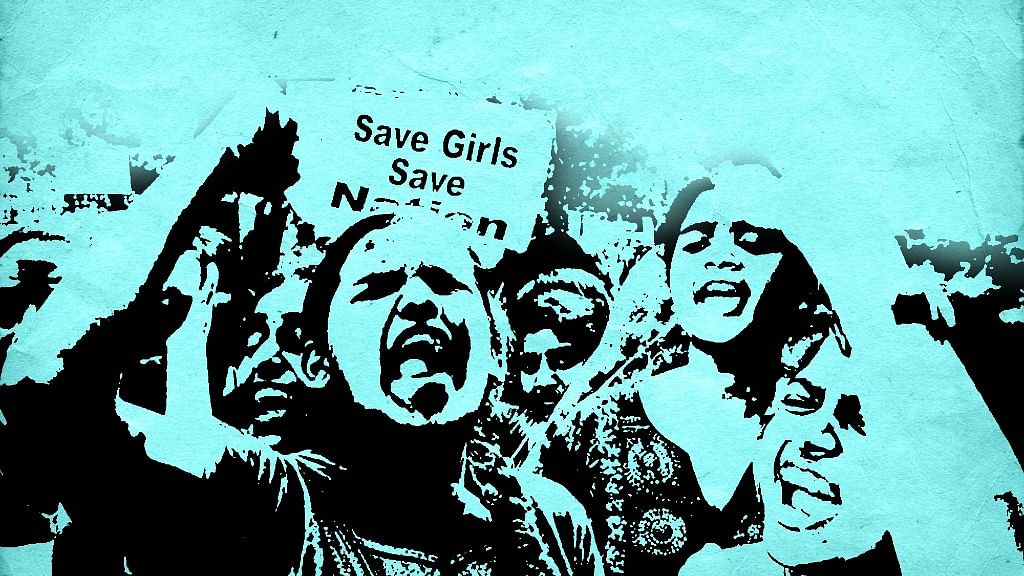

Historically, the women’s rights movements have questioned such discretionary powers exercised by state organs. These movements trace their origin to the abuse of power committed during the Emergency rule from 1975 to 1977. At that time, these movements focused on the rape of poor, formerly untouchable, and Muslim women in police custody and sexual molestation of tribal women.

The case that brought together different sections of the women’s movements was the Mathura Rape case of 1980. In it, the Supreme Court overruled the High Court judgement that gave the accused a seven-and-a-half-year prison term based on the argument that there was mutual consent.

Over time, the focus of these movements shifted from fighting the sexist mindset of state authorities to creating a women-friendly environment. This brought about the Vishaka Guidelines in the case of Vishaka and Ors. vs the State of Rajasthan, also known as the Bhanwari Devi case. The court held in this case that the right to equality regardless of gender, and the right to life and liberty under Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Constitution, were being violated.

Until 2013, when the Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 was adopted, these guidelines were the standard that obligated every organisation, irrespective of working in the private or public sector, to establish grievance redressal mechanisms for complaints related to sexual harassment.

However, the focus of all the welfare programmes for women has shifted towards removing the social stigma faced by the survivor through adequate remedies in the form of effective reparations. From an international perspective, the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to Remedy and Reparation for Victims, 2005, mandates that the victims of human rights abuses shall be provided full and effective reparations such as restitution, rehabilitation, and guarantee of non-repetition. Significantly, and important in our context, is the provision for rehabilitation including medical and psychological care in addition to legal services.

In this respect, in a recent judgement, the Supreme Court proscribed judges from making gender-stereotypical comments and stopped courts from prescribing marriage as a form of redressal between a sex offender and the survivor. These comments were made in the light of an appeal to a Madhya Pradesh High Court order that “allowed” the survivor to tie a rakhi on the accused.

Seen in this light, to achieve substantive equality between men and women, the social stigma that survivors of sexual violence face need to be addressed. This can be done by setting up a separate judicial forum or a women’s court that deals only with cases related to women in distress, by providing effective reparations and allowing them to live independently and not be seen as helpless.

An inspiring example is of the 22-year-old from Uttar Pradesh who was attacked with acid but it did not deter her from pursuing her dream to join the police force. The court awarded the accused life imprisonment in this case.

To conclude, the dialogue “A No means a No” from the movie Pink clearly explains that it is the consent of the woman that matters and her freedom to express herself that is of paramount significance, and nothing else.