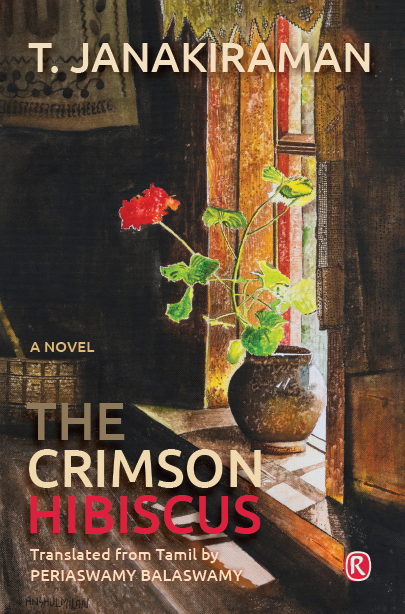

Set in the pre-Second world War decades in Tamil Nadu and considered among the best of Tamil novels, T Janakiraman’s Sembaruthi (The Crimson Hibiscus), translated into English by Periaswamy Balaswamy, is the story of an ordinary person, a shopkeeper, who is forced to give up studies and take up managing a small shop in a small town at a young age after his brother’s untimely death.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

People were rushing in short and long strides into the lane that leads to Mathukkulam Street from Market Street. Many curious people were cycling down in order to see things for themselves.

On Mathukkulam Street, people were standing in groups here and there. A big group of farm workers had occupied every place available in front of Seethaapathi’s house, near it and opposite. An old man was weeping… in a heart-rending manner. Another old man who had come from a slum of Ilancheri was lamenting loudly, ‘Let that fellow be avenged by goddess Kali, the wicked fellow who has killed…’

From a distance, Sattam saw a big cart in front of Seethaapathi’s house being loaded with a white object by policemen. Half a dozen men stood around. Sattanaathan was still some distance away when the vehicle started. People who were occupying the thinnais nearby came down and started following the vehicle, but at a distance in order not to anger the policemen. Silence filled the street. As Sattam was two houses away from Seethaapathi’s,

somebody stepped in his way, as if to obstruct him.

‘Namashkaram, Maapillai, sir.’

Sattam was taken aback on seeing Kishtamma. She had become thin. He had not seen her the past three or four years. Her mental derangement had worsened a few years ago and her relatives had got her admitted in the mental hospital in Madras.

He didn’t know when she had been discharged.

The tuft of hair on the back of her head was missing. They had shaved her head. There was three or four months’ growth of hair on her head.

Before Sattam began to enquire about her discharge, she started loudly, ‘I will declare with certainty who the murderer is. Iyer has no children, property of fifty velis. Being a philanthropist, he might have gifted his property to some college, school or hospital. This fear must have prompted his relatives to annihilate him. I am going to tell this to the police at the station. If they don’t receive my complaint, I will write to the Chief Minister. If they too don’t care, I will shout in front of the Governor’s palace.’ Then she turned in the direction of the departing vehicle and cried, ‘Ayyar sir! You will not see the fellow who killed you. He will be in hell and you will be in heaven . . . yes, you won’t see him.’ Her voice broke.

Sattam went into Seethaapathi’s house. A traditional, big house. Tall pillars, with a high, tiled roof. The walls, coated with a mixture of lime and eggshells, were shiny and smooth. All aspects of the house – the length and breadth of the hall; the largesized, framed Ravi Varma paintings of the goddesses Lakshmi and Saraswathi, of Thilothama and Mohini; the enlarged colour photographs of Seethaapathi’s grandfather and grandmother hanging on the walls; the oonjal, on which two could lie down comfortably; the high ceiling from which it was hanging; the chairs and sofas scattered all over the hall, with torn seats; two heads of horned deer fixed on the wall, looking down with glassy eyes – all this declared that the house belonged to a rich family.

Seethaapathi’s wife was sitting crouched against the wall, with her head down and knees up. As in old rich families, she wore diamond studs on her ears and nose. Her lips were red from having chewed betel the night before. Her complexion was fair. Her cheeks were stained with tears. The red kumkum mark between her brows was smeared. Her women relatives were sitting around her. The wives of the farm workers were standing

near the wall and the pillars.

Sattam stood at a slight distance from her. When Seethaapathi’s wife noticed him, she gave out a heart-breaking cry, ‘Amma!’ Her grief filled the whole big hall. Sattam started saying, ‘Amma,’ but he couldn’t proceed further. He closed his mouth and tried to control his sobs with a big sigh.

The other women moved away a little. Two or three got up and stood respectfully. It took a couple of minutes for Sattam to control his sobbing.

Seethaapathi’s wife cried out, ‘For you, your soul has gone. For me, everything is gone.’

She took a few minutes to control her weeping and said, ‘Now, for all these people, all the property due to them is gone. He said on two occasions, “Look here, you may perhaps die before me; but if, by some chance, your god wants it the other way round and I die first, be assured I will take care of your needs. I will leave this house, enough property for food and clothes for you. But the rest of the lands, I want to distribute to these workers.’’ Yesterday afternoon, he called the lawyer and was discussing it. Maybe that is the reason why this has happened. Now who will gift the lands to these people?’ She pointed at the wives of the farm workers.

The farm workers lamented, ‘Oh, our very life is gone. Who is bothered about the land?’

The wife continued, ‘Please go quickly. Later, you may not be able to see him whole. They say there will be a post-mortem. What are they going to find out? Would he have done all these things to himself? What else are they going to find out? I have been arguing with the Inspector all this time. He says that is the law. I was hoping they may listen to you, at least. Now they have taken him away.’

She seemed to be slightly disoriented . . . She had fainted once, they said.

Sattam rushed out to go to the government hospital. Bhuvana came in sight.

He told her, ‘They have taken the body to the hospital for a post-mortem. His wife is inside.’ He walked away. As he was going, he started to feel worried that Bhuvana might suffer a shock on seeing the wife. He stopped for a moment. Then he emptied his mind: ‘God, you are everything. This is your hibiscus flower. Please see that it does not droop.’ He then walked fast to the hospital.

The pigs of Sembanur ran before him, curling their tails and grunting.