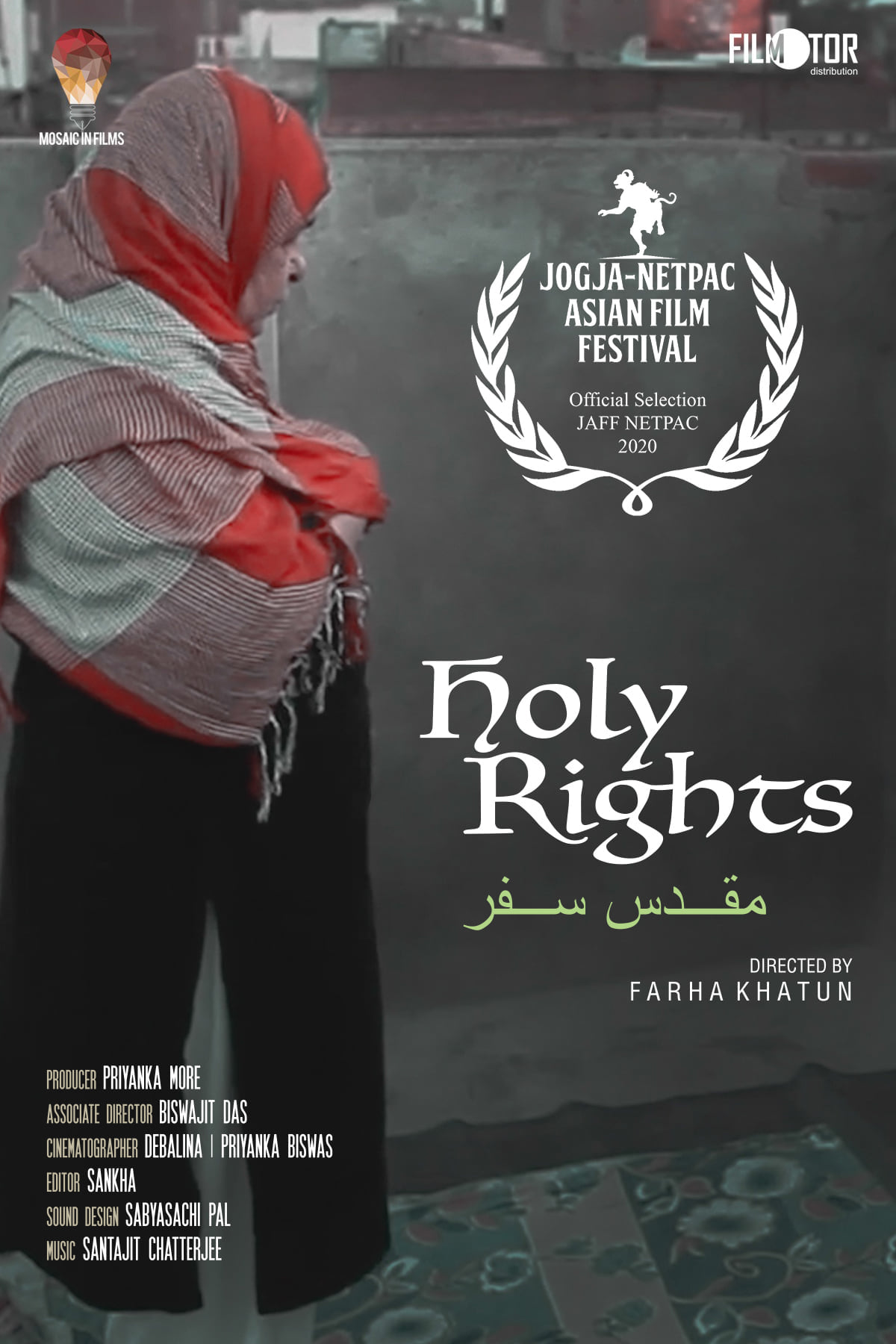

We see a white kite, cut off from its anchor, floating across the blue sky, to finally land, tattered and torn, on the branch of a skeletal tree, shorn of leaves or flowers. This is the opening frame of Farha Khatun’s new film, Holy Rights (2020), symbolic of the married Muslim woman who can be divorced and “set free” like a torn kite, at her husband’s whim. The film has by now been screened at around 16 national and international film festivals and has bagged six awards so far for Best Film, Best Director, Best Cinematographer, Best Story and Best Film on Gender Sensitivity.

Khatun’s film talks about the irony of conventional Muslim marriages, in which the husband can divorce his wife just by uttering the word “talaq” thrice – personally, over the phone, through email, or even via WhatsApp — following which the marriage is deemed null and void. What then happens to his wife and the children? How does she take care of the financial and social needs of the family without the support of the husband from within the patriarchal framework she was brought up and continues to exist in? Religious leaders actually sanction this practice though nowhere either in the Quran or in the Hadith is it mentioned that citing talaq three times can affect a divorce with immediate effect.

Safia, a devout Muslim woman from Bhopal, who joins a programme for training women as Qazis. It is through the lived experience of Safia Apa, and several other women who joined the programme, that the film comments on the arbitrariness of the wrong and illegal practice of instant triple talaq. We see the elderly Apa baking rotis rolled out by her old husband, on the griddle. When the voice-over points out how helpful her husband is, Safia Apa smiles and says that he is doing it because “now he is old and does not need to go out to work and with my severe spondylitis, I can no longer roll out the rotis so he must help”.

From this point on, we join Safia Apa on her very active and dynamic journey to raise social awareness and education among Muslim girls and women about their rights, because “according to Muslim social rules, rights are exclusively for the men and women must only do their duties”, she laughs. So, she points out that it is high time that women come out to assert their rights and do away with the middlemen and agents who call themselves Quazis and Mullahs.

Asked what the trigger to make this film was, Khanum says, “the influences I underwent as a Muslim girl growing up in the Muslim family from girlhood to womanhood shaped the concept and the idea of making this film,” adding, “I was quite aware of triple talaq since childhood. I have seen and heard many heart-wrenching stories about it, and they really affected and influenced me. My quest to know more about the act and its interpretation in The Quran led me to make a film on Safia, a woman Qazi.”

Khanum goes on to add, “Holy Rights documents the movement against triple talaq. It portrays Muslim women’s struggles to break free of patronising voices within the community as well as resist external forces against appropriating their movement to suit their own political agenda. Though the film talks about the Muslim community in particular, I believe it’s an all-pervasive one, on the problem of exploitation of powers of women. It also gives a message that all of us can achieve something if we want to.”

Safia moves around through the lanes, by lanes and streets of Bhopal with her sense of humour intact which invests the film with a mood that lightens the serious tone of the film and this is made possible because Safia is confident, educated, extremely well-informed but very grounded and witty. She is forever ready with direct quotes from the Quran complete with chapter and verse when a man confronts and challenges her at a press conference on the misquoting and misinterpretation by the Qazis on what is given in the Koran with reference to women, talaq, Iddat and so on.

Through her journeys into meetings with girls, walking through classes where girls are taught basic rights, we watch Safia crack jokes with women of different ages, many of them not even having passed high school and already married and/or divorced and making them laugh and have some fun and also learn about their rights.

One young woman narrates her tale of woe: “I had gone to visit my parents and when my husband asked me to return, I requested him that I stay for a day more and also that he come to pick me up. Without saying anything, he simply uttered the three words and divorced me. Can you imagine this violation of my person?” she asks. When the husband is summoned to the office of this group, he remains adamant and say that his talaq over the phone is according to his faith Islam and he will not go against it even at the cost of his life.

The film that took four years in the making, focusses on the work begun by Darul-e-Niswan, the organisation of Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan. This NGO began training Muslim women to become Qazis in April 2015 because according to Safia Apa, there is nothing in Quran that excludes women from becoming Qazis and performing marriages and other customary rituals that men have dominated for so long. Her argument is that if women are conversant with the Quran and its verses and rules, then no one can rob them of their rights as they already are well-versed in this. Safia Apa herself took this course and we find a group of grinning women of different ages being photographed holding the certificates proudly in their hands. This course has been running every year and when the film ends, we find the first woman Qazi conducting a Muslim marriage while there are others waiting in the queue to join in.

Safia tells the girls that the Quran uses the word “iqra” which means “read” and nowhere does it say that reading is exclusive to men so why shouldn’t women also learn to read? She says that no Qazi is entitled to declare fatwa against any woman because he does not have the right to do so.

The film offers glimpses into Safia’s personal life. We see her husband rifling through their old photographs in Black-and-White when they were students and we also see a photograph of the wedding ceremony and at different stages of their life.

The Supreme Court of India has declared triple talaq “unconstitutional” and also against Islam, making it a criminal offence from the 22nd of August, 2017. The ruling party BJP presented a bill in the Parliament that makes instant triple talaq a criminal offence with three years imprisonment. The Bill was passed on July 30, 2019, but feminist groups and human rights activists have expressed dissent at the criminalisation aspect of it.

We often find Safia Apa at the banks of a lake (Bhopal is called the city of lakes) gazing at a rudderless boat alongside other boats anchored at a distance. She keeps looking at the lake with its rudderless boat and clicks on her cell phone to photograph and also to learn the latest happenings at Delhi. This is an aesthetic touch and does not necessarily call for reading into it.

The only incident that sticks out is NDTV’s Ravish Kumar quoting the number of Muslims caught and killed for eating or storing or carrying beef which has absolutely no connection with the subject of the film. If the director used it to signify the sensitive times represented in the film, it does not work well. The musical score is soft and subtle and keeps going with the ambience of the film and never overpowers the content or the visuals. The cinematography is candid and captures Safia Apa in her various moods as it wanders across Bhopal, where the major slice of the action takes place, to move briefly to Kolkata and Mumbai. In fact, there is a lovely shot of the women visiting a fair to buy trinkets where one shot shows a wall covered completely with portraits of Hindu Gods.

Khatun’s debut documentary, I am Bonnie, was on the tragedy of how the life and career of a talented footballer lie in debris as he chose to change his sex, and it had won several awards and was screened in several festivals. Holy Rights is her second documentary that spans around 52 minutes of screening time.