A string of concerns of home and belonging, displacement and othering haunt the present day India as much as they do countries of the Global north, perpetually negotiating their angst about the people that “do not belong” there. Argentinian theatremaker Lola Arias’s play Futureland brings the universality of these stories into the fore, building a suggestive transference of the fear that was palpable during the introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) passed by the BJP in 2019 despite months-long massive protests by citizens. The director has an international reputation as an artist who places real life on stage. The production begins with the launch of eight unaccompanied minors from a plane into an abyss sans a parachute; Mamadou, Faiya, Bashar, Sarah, Sagal, Ahmed, Mohamed and May. The interwoven testimonies by these characters depict the urgent crisis of displacement of refugees and also the larger question of civic and social citizenship — a contemporary dilemma raging in many modern nation states at the verge of turning into illiberal democracies. The pending implementation of the CAA is one amongst many such neoliberal Islamophobic projects bordering on right wing paranoia about a legal and historical claim to the native place.

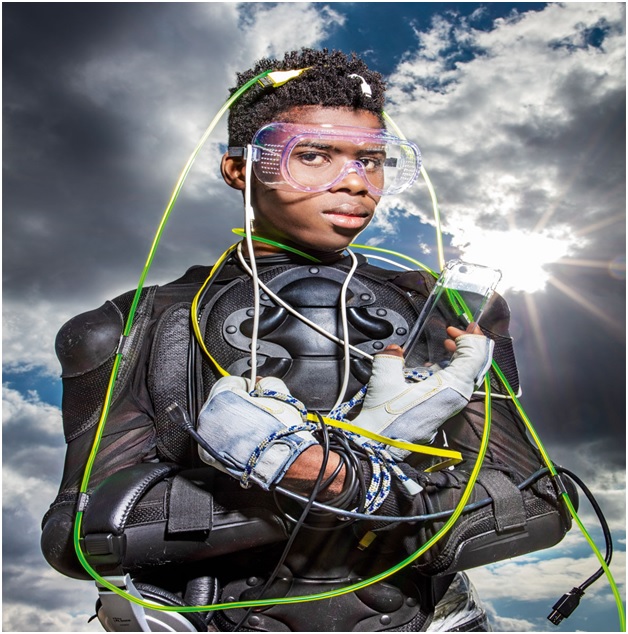

During the play, there are several intermediate strong moments where a process of magnification takes place. Concerns of home, fear and displacement turn into a shared civilisational anxiety. The play gesticulates at the urgent contemporary echo of fascist developments along with the rise of anti-minority sentiments. Technology is symbolised in the play not only as an actor but also as an agent of displacement. In the process of displacement it becomes a weapon of unchecked violence and the promise of the internet unravels itself as false. Margins also have their ossified centers in which othering is an everyday phenomenon. By juxtaposing felt tragedies of displacement the play succeeds in highlighting the plight of the Global South countries — Syria, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Somalia and Guinea, as cultures and polities inflicted by decades of war on their resources by the Global North.

In the multicultural success story of minor refugees and the travails of their journeys, the dystopian urbanscape is inspired by the online video game PUBG- PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds as a futuristic version of real estate development happening right in the middle of a not so modern humanitarian crisis corresponding to the construction of smart cities in the third world, despite festering economic and social inequity. Interestingly, all shops have a similar signboard of “Burgers” illustrating the vast expansion of cultural and political hegemony. The digital landscape is a metaphor for the Panopticon of the modern military — industrial-surveillance complex — the big brother is constantly watching you with the right set of consequences whose price might be more than your life. The screen showcases only one female avatar through which one feels the familiar andocentric take on law and bureaucracy. The story plot indicates a socio-political stance about whether the basic right to shelter can be inalienable. The minors might not have had any agency in their homelands and consequent journeys but in Futureland, all of them possess possibilities towards a reinvention of their futures, because in their own articulation, “Futureland is the land where everything is possible”. But the information the performers have about the fate of their lives continues to be precarious on account of a forced, homogenous process of integration and the usage of legal terminologies like tolerance permits that reek of prejudice and apathy. The play brings to the fore the demobilising effects of displacement, compounded by bold narratives interwoven with traces of xenophobia, racism and Islamophobia.

Much like the impending Citizenship Amendment Act that superimposes the Hindu majority over all minorities, the idea of one language-one dress-one culture is forced on the minors while simultaneously relegating them to the lowest rung of the German economy with castigation and deportation just being a click away. Even the rampant use of biometrics (Aadhar, anyone!) to claim superiority over a certain race and class of people is depicted through a series of medical tests. The characters embody all impoverished lives whose caste and class can be judged from the texture of the skin and hair to the quality of the clothes. Caught in a fracture of time and geographies, these characters garner universal appeal in foraging and cementing horizontal and vertical solidarities. These are stories that have already crossed a certain threshold of documentation, liberation, comprehension and yet drive home the carnage of displacement. It is the conscious act of retelling their own life stories by the performers that gives the utmost sense of justice and power. One slowly becomes aware here that this is no act and yet an act showcasing a hegemonic process of displacement through a democratic one of theatre.

In the current raging pandemic and the resultant digitisation of life and livelihood — the digital aura takes an altogether different meaning wherein to survive in the real world, one has to operate by the rules of the digital that is not tangible yet powerful. It is emancipation and freedom that become intangible and unattainable. Extremely fundamental concerns of migration, surveillance, cultural and linguistic hegemony, homeland, and socio-political structures are all presented together as correlated issues. The performance constructs citizenship as an aspiration towards an ideal social representation. By connecting the dots to the draconian Citizenship Amendment Act that might displace the religious minority population of Muslims and other minorities like Dalits and queer sexualities — one feels a haunting similarity in the prospects awaiting marginalised bodies all over the world where people can be empirically subjected to displacement. One feels ambushed by the rising unease and angst at chances of being put in a detention center, ending up rootless as a lesser citizen during the course of the performance of Futureland. Even if Mamadou, Faiya, Bashar, Sarah, Sagal, Ahmed, Mohamed and May get integrated, would it be an equal citizenship? Here the play very concisely bridges the gap in perceiving an act and its actual reality. As a farewell song, I am going to fight you all becomes a solidarity call for a new world order.