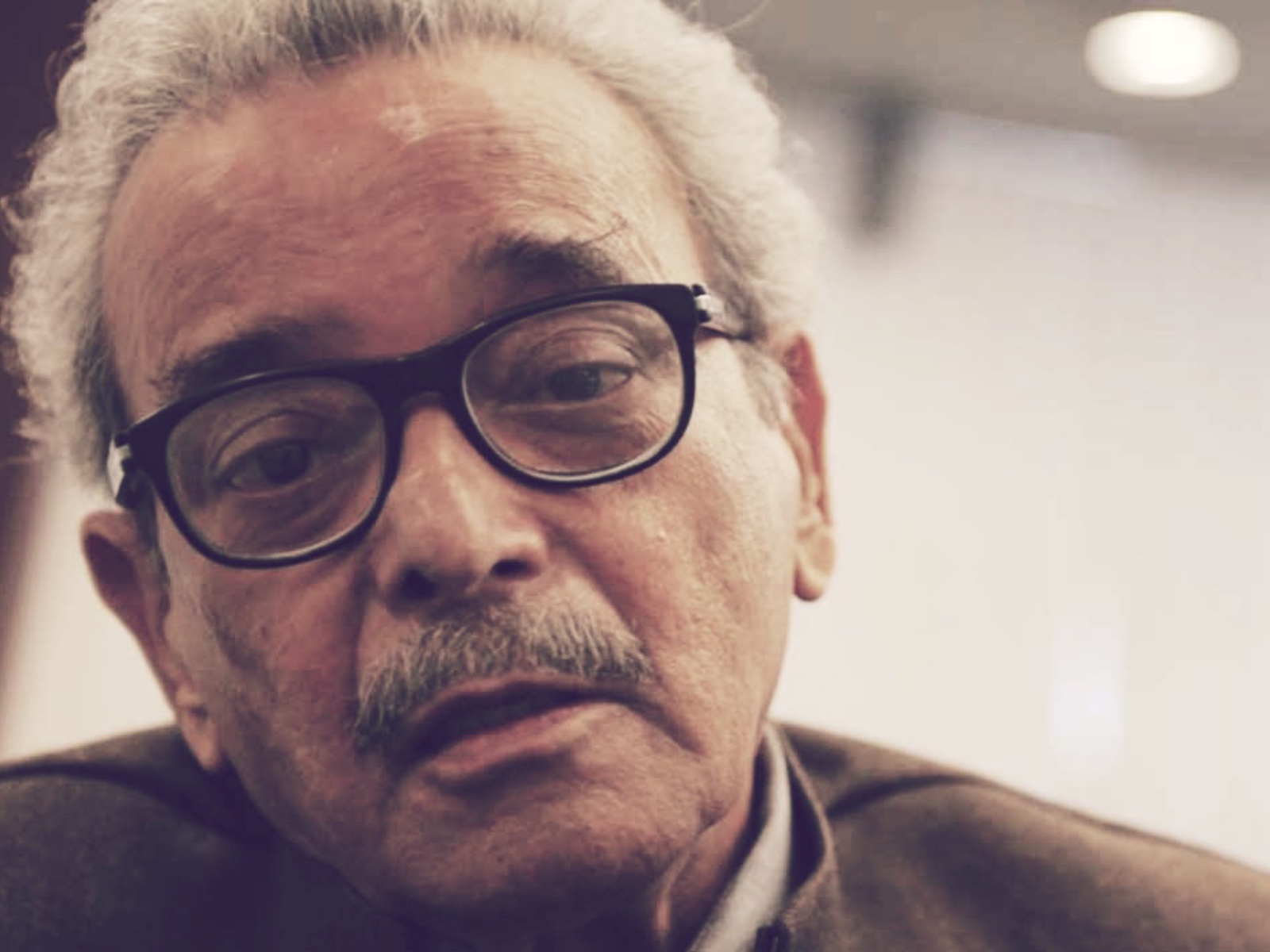

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s death on December 25, 2020 has left a huge vacuum in the literary cultures of North India in general and Urdu literature in particular. For close to half a century, he strode the Urdu literary landscape like a colossus, first as a pioneering critic and literary-cultural historian and then as a creative writer. Scholarly rigour and urbane eclecticism characterised much of his corpus. His contributions to the world of letters were recognised by multiple awards and honours in India and abroad. He could straddle the entire landscape of critical thought between Leavis, IA Richards and Derrida on the one hand, and Hali, Shibli, MH Askari and Suroor on the other, with Jurjani and Khaqani and Anandavardhan thrown in for good measure, with ease and felicity. He was scholar-writer for the informed, the initiated, the cognoscenti, making demands on his readers and yielding commensurate rewards. Among his interlocutors in India were critics and writers from different languages like Namvar Singh, Harish Trivedi, Ashok Vajpeyi, UR Ananthamurthy, K Satchidanandan, to name only some, that indicate his range and catholicity.

Faruqi Saab liked to sail against the current, as an original mind tends to do, and to read writers and texts against the grain.

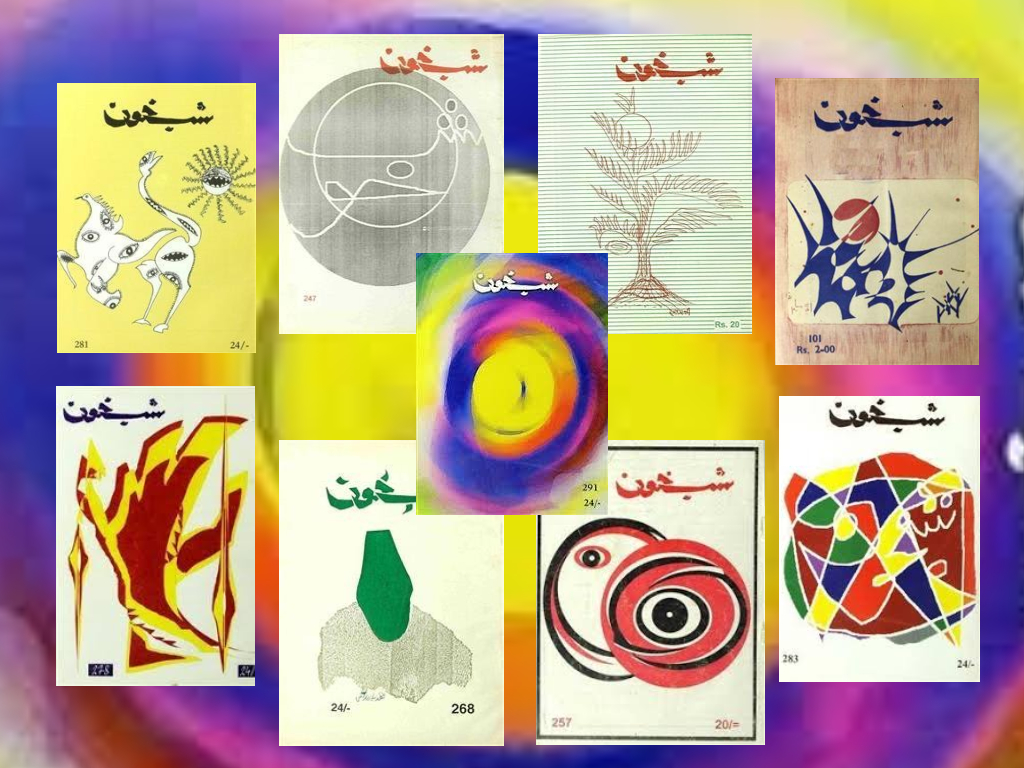

Hailing from a tradition of officer-scholars, Faruqi was a civil servant who completed his full tenure of government service, retiring as the Chief Postmaster General, even while making significant interventions in the literary realm. Shabkhoon, the journal that he edited single-handedly heralded and nurtured modernism in Urdu and ran for four decades. It helped a generation of writers finding their voice and honing their art in the post-progressive era of Urdu literature. Going through its pages with a long historical view indicates how newness entered the world of Urdu literature and criticism, sometimes laden with quite hackneyed images, stock situations and largely impressionistic views. Readers eagerly waited for each issue of the journal to know about new writings in Urdu and Hindi and trends in criticism that promised new ways of evaluating literature, as they later did for the Annual of Urdu Studies (University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA) where Faruqi occasionally published his seminal essays in English. Two such essays that immediately come to mind are, “Unprivileged Power: The Strange Case of Persian (and Urdu) in the Nineteenth Century” and “Conventions of Love, Love of Conventions: Urdu Love Poetry in the Eighteenth Century”. These essays, combined with the volume, Early Urdu Literary Culture and History (OUP, 2001) and his long exegesis, “A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture” in Sheldon Pollock’s tome, Literary Cultures in History contain invaluable resources for anyone researching Urdu’s literary culture and history.

He is a notable exemplar of the artist who could hold these two faculties in perfect balance by composing poetry and fiction at frequent intervals.

Firmly rooted in his tradition but a cosmopolite in outlook, taste, vision and scholarly engagement is how I would like to characterise him. His love of tradition led him to explore and recover the lost art of dastangoi for contemporary readers, defining its poetics and historical importance in the context of Indo-Muslim civilisational and literary encounter. This he did in a string of essays and a series of volumes with the title, Sahiri, Shahi, Sahibqirani: Daastan-e Amir Hamza ka Muta’la, 5 volumes of which have come out so far, the fifth volume he held in his hands, fresh from the press, a couple of days before his death. The first 3 volumes deal with the theoretical studies of Dastaan, the rest of the volumes were supposed to be extensive interpretation and commentaries on all the 46 monumental volumes of Daastan-e Amir Hamza that adorned his library and were his prized possessions. What a pity that this work, in all likelihood, will remain unfinished as no other scholar seems equal to the task.

Faruqi Saab liked to sail against the current, as an original mind tends to do, and to read writers and texts against the grain. It is, perhaps, this contrarian impulse that led him to make the eighteenth-century poet, Mir Taqi Mir (and not nineteenth-century poet, Ghalib, everyone’s preferred favourite) the core project of his most formative period. Sher o Shor-angez in 4 volumes contains his extensive interpretation and masterful analysis of Mir’s poetry and won for him the Saraswati Samman. It does not, however, mean that he gave short shrift to Ghalib who, too, remained a life-long passion with him, and the subject of many essays and two full length books — Tafheem-e Ghalib and Ghalib par Chaar Tahrirein.

His life will continue to inspire many of us as it demonstrates how much a dedicated scholar can achieve in one lifetime, and that age is no bar to creativity.

Traditional wisdom has it that the critical and creative faculties are antagonistic to each other, an assumption that he challenged, and demonstrated the opposite by his own practice. He is a notable exemplar of the artist who could hold these two faculties in perfect balance by composing poetry and fiction at frequent intervals and then producing one of the three masterpieces of Urdu fiction, Kai Chaand the Sar-e asmaan — the other two being Qurratulain Hyder’s Aag ka Darya and Abdullah Husain’s Udaas Naslein — at the ripe age of seventy when many writers would like to hang up their gloves and bask in the glory of their achievements. It is the work of a stupendous literary imagination and a keen historical sensibility. I quote (with apologies) from my own review of the English version, Mirror of Beauty published in the Indian Express:

‘The narrator goes right to the heart of the book when he says about Wasim Jafar, a descendant of Wazir Khanum, the protagonist of the book: “… he rejected the notion that the past is a foreign country and strangers who visit there cannot comprehend its language …” The past is not a foreign country for Faruqi, steeped as he is in the literary culture of the 18th and 19th centuries, a culture that represented the best of Indo-Muslim heritage, a period in which a galaxy of Persian and Urdu (‘Hindi’ in Faruqi’s characterisation) poets appeared on the scene, each more accomplished than the other. Faruqi’s endeavour in the novel is to recreate that age and its mores as exemplified in its poetry, music and painting, through the persona of Wazir Khanum, a woman of near-perfect beauty and accomplishments, grit and grace. In the 1000-odd pages, divided into seven books, 68 chapters and two interludes, Faruqi deals with the antecedents and vicissitudes of Wazir Khanum’s life, the declining years of the Mughal empire, the tenuous relationship between the would-be rulers and the Haveli (the Red Fort) and the colourful officials of the Company Bahadur, all historical figures, who combined a certain admiration for Delhi’s culture with utmost ruthlessness to any kind of opposition to their authority.’

Faruqi Saab was an engaging speaker. His lectures at Columbia University and the universities of Pennsylvania, Chicago and Wisconsin would leave his students spellbound. He was frequently invited to speak at the three central universities of Delhi, more frequently in Jamia Millia Islamia where he held the Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan chair some years ago. In the English department, we were particularly privileged because his daughter, Baran, works here, and he always treated us with extreme indulgence and generosity, rarely declining a request to be with us. (His elder daughter, Mehr Afshan Faruqi, from the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, USA, was in Jamia during the Spring semester as a visiting professor. She was held up in Allahabad because of the pandemic, and it must have afforded her the opportunity to spend quality time with her father). As Baran lives close to the campus and Faruqi Saab stayed with her on his visits to Delhi, the campus community eagerly waited for his arrival, some to run their hypotheses past him and take his opinion, some to work out obscure literary allusions, and his friends to fill him in with the latest literary happenings. A refined conversationalist in informal gatherings, full of wit and repartee and a capacious memory for English and Urdu poetry , he would occasionally let his hair down to deliver a devastating punch (metaphorically) to his adversaries, but would always enliven the atmosphere by his cleansing, boisterous laughter. My last meeting (virtual) with him happened last month when he delivered the keynote to a multi-lingual workshop held by HRDC, Jamia, in which I had the opportunity to be with him, exchanging greetings and pleasantries. There was absolutely no sign of any decline in his intellectual grip or mental alertness.

Despite living a life given to scholarship and intellectual inquiry, Faruqi Saab was a devoted family man – a loving husband devastated by his wife’s untimely demise, a deeply caring father to his two daughters, a doting grandfather to his grand children, and a great grand-dad too, a role he performed with great aplomb. All of them, on their turn, adored him, and must be inconsolable at this moment. We share their grief in all its intensity. But it will be a matter of some consolation to us that during his final days he was surrounded by his near and dear ones, that his two daughters were taking care of him like two good fairies, and that everything was done that could possibly have been done to make him comfortable and help him recuperate.

Faruqi Saab’s life will continue to inspire many of us as it demonstrates how much a dedicated scholar can achieve in one lifetime, and that age is no bar to creativity. He lived a life of the mind and will live in the mind of many for a long time to come.