The cliché, “the end of an era” is literally true in the case of Sugathakumari’s passing away in Thiruvananthapuram, on 23 December, at the age of eighty-six. She produced some of the most iconic works of Malayalam poetry during her illustrious poetic career spanning almost six decades, during which she won major honours and awards including Sahitya Akademi Award (1979), Saraswati Samman (2012), Ezhuthachan Award (2009) and Padma Shri (2006). Her transformation into a leading social activist from the 1980s onwards, was not a premeditated step. She threw herself into the vortex of the struggle for preserving the Silent Valley in 1980, when she understood the environmental cost of such a mindless destruction of a primal forest.

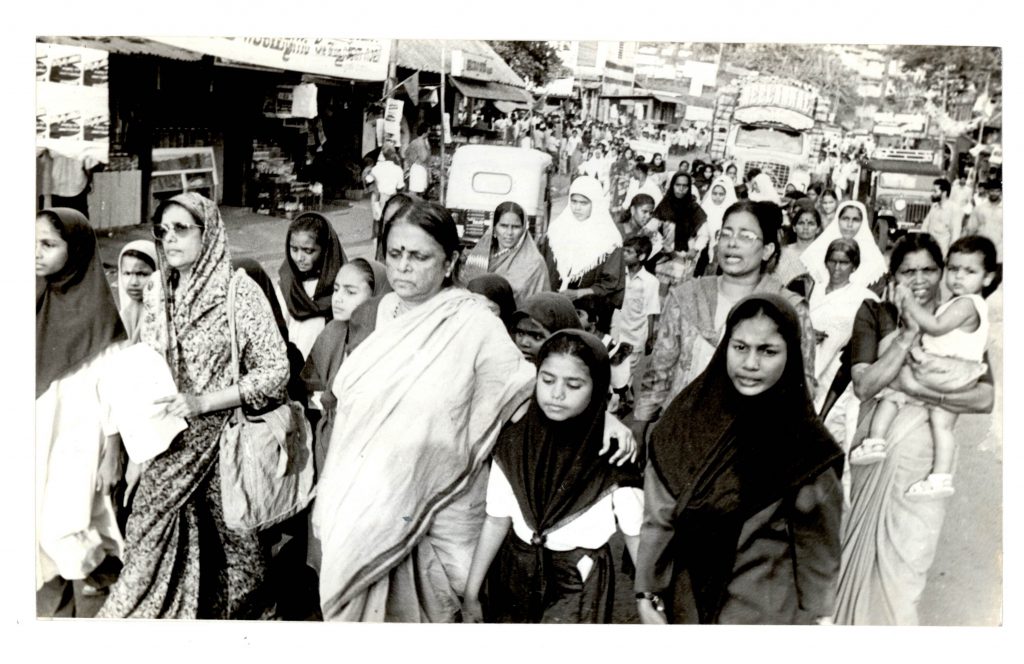

Her social work for the cause of the destitute and the disabled women trapped in mental asylums and the victims of sexual violence also originated from her first-hand experiences of their horrors. In one of my meetings with her in Thriuvananthapuram in 2014, she narrated recent episodes of sexual violence in Kerala which left me numb. Her work was not easy, and the risks involved were real. Her relentless quest for justice in a world which had lost its sense of direction has no parallel in the lives of authors in recent history of Kerala. She founded institutions like “Abhaya” and “Athani” which are now beacons of light in a dark world. When she became the Chairperson of Kerala State Women’s Commission in 1996, she initiated many grass-root level programmes to ensure women’s safety. Hers was the voice of Kerala’s conscience, fearlessly upholding the rights of the oppressed and the marginalised.

Sugathakumari’s father, Bodheswaran was a Gandhian social worker and a poet whose habit of reciting poetry loudly appears to have left a deep impression on his young daughter. Her mother, VK Karthyayani Amma was a Professor of Sanskrit who initiated her into classics. Both her sisters, Hridayakumari and Sujathadevi were well-known writers and their loss in the last decade had left a void in the mind of the poet who was very close to them. She did her Honours in Philosophy and did not pursue an academic career despite an invitation to join the University college in Thiruvananthapuram. She married Dr. Velayudhan Nair, an educationist, who worked in Delhi. They spent almost a decade in Delhi before they returned to Thiruvananthapuram, where Sugathakumari busied herself with the work of the State Institute of Children’s Literature where she edited a magazine for children. Her husband was very protective of his talented wife, and shielded her from the pressures of everyday life. Her only daughter, Lakshmi, a poet with two volumes, has been her source of strength in these last years of her life.

Sugathakumari began publishing poetry in the 1950s. That was the time when some of the legendary Malayalam poets such as G Sankara Kurup, Balamani Amma, Vyloppilli Sreedhara Menon and Edasseri Govindan Nair were active. Her talent was spotted by N V Krishna Warrior who edited the literary weekly, Mathrubhumi. By the late 1950s, a new poetic sensibility was taking shape, as a new generation of poets had begun moving away from the prevailing conceptual horizons of poetry. Sugathakumari’s poems appealed to a large audience because her unwavering mastery over diction and metre spoke of her deep roots in the tradition of Malayalam poetry, even as she conveyed the anguish and the angst of a distraught mind caught in the existential struggles of a changing society. She followed her own instincts in chartering a poetic journey which explored the intimate emotional states of a mind in turmoil. One of her early poems, “Kaliyamardanam”, uses the myth of Krishna dancing on the hoods of the Kaliya, the vicious serpent. Her treatment of the myth retells the myth from the perspective of the serpent, rendering the idea of the divine ambivalent:

Never were these hoods lowered

Never did this soul weep…

Do not ever stop the dance;

My soul merges into a rapturous cadence.

(Translated by Atmaraman)

The dance becomes a state of conflict and contingency which cannot be resolved in the traditional idiom of devotion. It is Sugathakumari’s ability to plumb the depths of her creative self that produced some of the enduring poems of love in Malayalam. In one of her well-known poems, “Pavam manava hridayam” (The Poor Human Heart) she conveys man’s need to cling to hope and look for signs of life in any bleak landscape. The poem ends with these lines:

When it sees a star, it forgets the night

When it sees the first showers, it forgets the long drought

When it sees a baby’s milky smile, it forgets death

Happiness fills it then

This poor human heart.

(Translated by Hridayakumari)

The lyricism of her poetic lines and their harmonious movement forge an affirmative vision which transcends the morbid forces that overwhelm her. Her poems often invoke the figure of Krishna in such moments of extreme anguish. Her volume of poems, titled Krishnakavitakal, captures the range of moods and themes associated with the various shades of the Krishna myth.

In her best poems she is able to objectify the moral crisis of the modern woman caught in the everyday struggles of a male-dominated world. But it is important to note that she never subscribes to a feminist position that interprets reality through the lens of gender. The myth of Radha and Krishna appeals to her mainly because it enables her to go beyond the binaries of the male and female. When she was confronted with the harrowing plight of women in the mental asylums, she took up their issue in public life. Her poem, “Rain-at-Night” invokes the figure of the lonely woman who is consigned to a black hole with no hope of redemption:

Rain-at-night

Like some young mad woman

Weeping, laughing, whimpering

Muttering without stop

For nothing

Sitting huddled up

Tossing her long hair

(Translated by Hridayakumari)

The voice of the distraught soul that pervades her early poetry progressively deepens into a deep social concern in her post-1980 poems. It is a natural development which did not disrupt her poetic style. It is her ability to assimilate new themes and a refreshingly personal critical voice that enabled her to reinvent her poetry in the post-1980 period when modernist poetry gave way to a new idiom.

Even when her concerns increasingly turned towards the public world, she did not write ‘public’ poetry with a strident voice. Her brooding poetic voice now becomes more reflective and she questions the nature of evil in the world. In a poem titled “Temple Bells”, she says:

The temple bell, its edges cracked;

It still sings to the wind’s touch.

But who is there to listen now?

How to hear this tinkle

Amidst the market’s din

And the leader’s roar

In the public square?

Who cares for this frail, feeble music

Amidst lusty lurid songs

Sizzling away in movie theatres?

(Translated by P P Raveendran)

The temple bell here seems to suggest the inner voice embodied in the poet’s speech which has lost its relevance in the world of the market and the spectacle. But she would rather cling to its gift of melody and its life-giving primal lustre. Her poems move on a plane where divisions and labels lose their meaning.

It is her inclusive vision rooted in the personal that has enabled her to walk with the five generations of poets from the 1950s to the second decade of the twenty first century and remain contemporaneous with all of them. Faced with the horrors of the new century, she wrote in the poem, “No human language can contain this”: “Be silent, it is the hour to / stand mute with bent heads”. She even renounced poetry once saying there is no poetry left in her soul. But she came back to poetry with renewed vigour and continued to speak on behalf of those who are condemned to the living hell of violence and injustice, in an idiom which goes straight into your heart. In the poem, “The girl child in the nineties”, the mother who speaks has no choice but to abandon her child in the holy courtyard of an orphanage. The lines from the poem haunt you like a piercing cry from the dark, with its accent on the unspeakable cruelty of our times towards the girl-child. In the poem, “The Women’s Commission”, she narrates the litany of woes the brutalized women recount in each of her meetings with them. The poem shakes your conscience with its pointed questions towards the kind of society we have created:

They curse, they come

my daughter, my mother,

my sister, my child,

they come in hordes and they curse

They come crawling

with a noose around their throat

They come with battered, bruised body

They come burnt black by fire

They come drowned in agony

holding their swollen belly

wailing like lost souls

But they come holding high their anklet

with smouldering eyes

(Translated by Sugathakumari)

Here her personal voice seems to merge into the collective voice of all suffering women. Their “smouldering eyes”, she knew, concealed volcanic eruptions that could burn down the modern world.

Sugathakumari’s role as an environmentalist merits a detailed essay. In one of her interviews, she recounts how she could not sleep for days together when she heard that a hydro-electric project was to come up in the rain forests of the Silent Valley. It was in 1980. She knew she had to act, and act she did. Prakriti Samrakshana Samiti, an alliance of writers, scientists, activists and common people committed to environmental causes, took Kerala by storm. If finally, the government retreated from the project, it was the result of the relentless campaigns unleashed by the activists and the media. The poems of Sugathakumari played an important role in mobilizing public opinion. Her poems such as “Hymn to a tree” and “An ode to River Thames” etc are etched in the memory of those who participated in those battles for ecological justice. She also faced criticism from many quarters, vested interests groups calling her “marakkavi” (a poet of wood) etc. She stood her ground and faced the fury of the opponents with composure and understanding.

It is important to put on record what Sugathakumari stood for and fought for. In pursuing her personal truth and inner voice, her poetic self evolved into a public figure with a moral vision, showing the way in a world torn between greed and violence. We may not see one like her for a long time to come.