At first sight, it may seem rather strange that the people of India, a country which boasts of a written treatise, the Kamasutra, on erotica, penned thousands of years ago, should be so squeamish about erotica. But upon reflection, you find it quite logical. Beginning with the Kamasutra itself, most depictions of mutually enjoyed sex in our literature were those that occurred outside marriage. They were frowned upon for being immoral, but savored for the titillation afforded by the immorality.

Conjugal love was hardly ever portrayed with sensual or even sensuous connotations. The emphasis was on devotion and lust — devotion on the wife’s part and lust on the husband’s! To some extent, the reticence to celebrate conjugal sex can be explained by our double standards vis-à-vis men and women. But the real reason lay deeper. We were willing to accept intense sexual love as an aberrant behavior but not as a natural or desirable ingredient of daily life. We want to keep the purveyors of pleasure and family loyalties apart.

We were willing to allow men and women enjoy erotic love, at least in poetry and fiction, as long as it did not impinge upon familial and social obligations.

When we look at our ancient literature, we find a paradoxical situation. In the Ramayana, which was probably one of the first written love poems, we find the chief protagonist, Ram, in a perpetual dilemma between love for his wife and duty to his family and kingship. Most of the time, his words and actions are those of a lover, but as soon as he takes on the mantle of the righteous king or a suspicious husband on public demand, he becomes squeamish about conjugal love. Remember his lament as Lakshman lay dying during the war with Ravan. Alas, to sacrifice brother for wife! It was because love for the wife reeked of sex that it could not be put on par with love for the brother. Later, when he has to choose between proving himself a righteous king or a fair conjugal lover, kingship wins hands down. Sita is banished on account of stray slander.

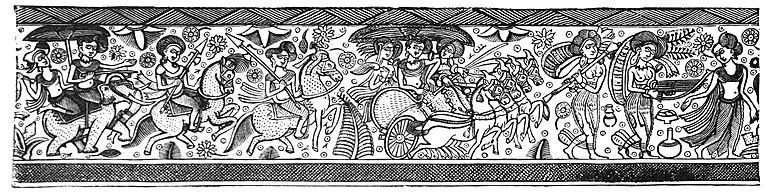

No wonder that latter day erotic poets like Jaidev preferred to sing of Radha and Krishna, both married to other people. Readers in turn loved them for not only being divine and “above human” mores, but also for not being married to each other. We were willing to allow men and women enjoy erotic love, at least in poetry and fiction, as long as it did not impinge upon familial and social obligations.

One notable exception was Kalidasa’s Meghdootam. Its erotica sprang from the uncensored yearning of an estranged husband for his sexually active wife. But considering that it was the same Kalidasa who had husband turned lover Dushyant, spurn his lost and found wife Shakuntaala in Abhigyan Shakuntalam, it would be fair to surmise that the unbridled passion of the husband in Meghdootam, sprang from his being cursed away from the conjugal bed. When the husband (yaksha) penned the erotic message for his unavailable wife, he was, for all practical purposes, indulging in illicit love.

The decision of the lovers in Tagore’s novel, Shesher Kabita, not to marry because they were too passionately in love was a throwback to the same attitude. By then, however, we were so corrupted by Victorian puritan mores that we had begun to frown upon all depictions of sexual enjoyment, even those outside marriage.

Modern Hindi and Urdu writers like Bechan Sharma Ugra, Ismat Chugtai, Manto, Krishna Sobti, Krishna Baldev Vaid, Manohar Shyam Joshi and yours truly have all been maligned by Hindi critics for depicting erotica, not as a source of titillation, but an essential and serious part of everyday life.

We are all familiar with the argument of moral pundits that prostitution is a necessary evil for keeping the rest of the society pure. Pornography is viewed in the same light. It was pleasurable because it titillated and shocked, but as long as it remained aberrant and not likely to be imitated by respectable people, it could safely be regarded as a “necessary evil”. Tales of erotica which question the value system and codes of conduct are the ones which turned out to be “problematic”. They are perceived as threats by the keepers of morality, and maligned and banned. I have learnt from personal experience that our critics are more peeved by erotica than pornography.

In 1981, my play Ek Aur Ajnabi was to be telecast by Delhi Doordarshan, a few years after being awarded and aired by All India Radio from many stations, in many Indian languages. A day before the telecast, however, it was banned by the order of the then Director General. When I asked him why, he first said it was because it was against the institution of marriage. When I reminded him that a week before he had beamed a play in which the wife had asked a jinni for a playmate other than the husband, he shrugged and said, “That’s different. Your play makes people think!”

The liberators of the female body seldom concern themselves with the female mind.

The cat was out of the bag. By “think”, he meant “question” our image of who we and others were and what we could become, given a choice. Our literary critics did not want people to think for themselves and realise that there was nothing forbidding or forbidden about sexual love.

His reply also made me understand why I had been arrested for my novel Chittacobra in 1979. There was nothing pornographic about it but it sure was erotic. It not only revelled in sexual love outside marriage, it committed the graver sin of having a woman think, not of another man but of analytical issues with a man on top of her; the husband to boot. How dare a woman reduce her husband to a mere body; he whom she was bound to love but never lust for?

Modern day Hindi fiction is replete with tales of graphic sex. Women writers like Maitreyi Pushpa, Ramnika Gupta, Kavita, Geetashri and many others swear by the freedom of the female body. But when it comes to depiction of female sexuality, they treat it in the same way as men, in accordance with time-honoured female myths and male fantasies. The liberators of the female body seldom concern themselves with the female mind.

Here is an account of some of the more popular myths regarding women:

1. Women need love to derive pleasure from sex while men are fine with just sex.

Strange that no one has stopped to think that since the biological attributes of women allow them to fake orgasm, what prevents them from faking protestations of love?

2. Women share their intimate feelings with each other while men do not.

My otherwise favorite playwright Mahesh Elkunchwar’s play Sonata has won particular acclaim for his insightful foray into the female psyche. I have nothing but admiration for the literary merit and theatrical craft of the play, but as a private and reserved person or woman, I could not help wonder how he reached the conclusion about women sharing intimacies? Did he eavesdrop on women’s private conversations or was it wishful thinking? Were the men who delighted in this fantasy not in denial of their own intimate locker room conversation with other men?

I asked Elkunchwar at a meeting of the Natrang Pratishthan in Delhi why he had not written a play about men if he wanted to delve into the secret chambers of the human mind? Surely, he could have written about their ribald sexual jokes and shared fear of castrating female aggressiveness with greater probity. He reiterated his belief that women were more candid with each other than men. I was not convinced and still am not. I feel the real problem was that tackling heterosexual men’s intimacy was too close for comfort and also not as saleable as women’s disclosures.

3. Middle class housewives routinely fantasize about unbridled sex.

It started with Erica Jong’s novel Fear of Flying, published in 1973, which has held Indian male psyche in thrall ever since. I would expect women to fantasise more about becoming rich and famous models, film stars, chief executives, judges or Chief Ministers, but I guess that is too frightening a scenario. An Indira Gandhi here or a Mayawati there can be born, but it would be intolerable to believe that the neighbor’s wife was aspiring to be one of them.

4. (The mother of all myths) Virginity is synonymous with unbroken hymen and the pain of having it torn enhances pleasure, making the first sexual encounter unique for women.

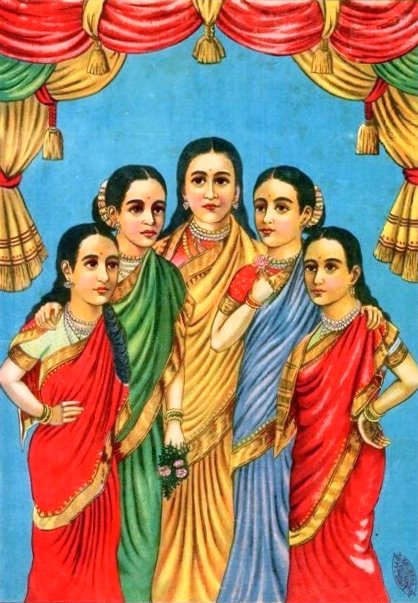

In this context, the mythical lore of the fabled Panchkanya is quite fascinating. Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, have multiple consorts, yet are deemed virgins because of a boon they share; their hymen becomes intact after sexual intercourse. This can be considered a boon only if one believes that pain enhances sexual pleasure. If that was true, it would have applied equally to men and women. Since it is a myth, it is perforce female!

The subtext is rather interesting. There is an obvious insinuation that it is more pleasurable to have sex with different men than with the same man repeatedly. Even then, an intact hymen has nothing to do with it. The first sexual intercourse is unique for both women with punctured hymens (sometimes caused by playing sports or doing strenuous exercises) and those with intact ones. It is unique in the same way that any new experience is; climbing a mountain, diving in the sea, getting caught in an earthquake, giving birth to a child or getting a stye in the eye. The experience may occur a second or third time, but the novelty can never be replicated.

It is a pity that most women writers of the present generation have internalised male sexual fantasies or female myths even more than the earlier generation.

A more coherent reason for one’s first sexual experience being pleasurable is the inherent knowledge that the second time would be better with the hymen out of the way. Anticipation enhances pleasure. Philosophically speaking though, one could say a woman was a kanya (virgin) as long as she was anticipating and waiting for the perfect orgasm.

It is a pity that most women writers of the present generation have internalised male sexual fantasies or female myths even more than the earlier generation. When we, the older generation, have tried to break the myths, they are revelling in them. They give graphic details of sexual acts almost in the manner of a sex manual, in the name of liberation. They fail to realise, however, that it is bondage to hold on to the myths about women propagated by men for men.

Most contemporary novels in Hindi accommodate the myths because they are sops to male ego and favour pornography rather than erotica. But as with most conventions, there are exceptions. A notable one is Vinod Kumar Shukla’s novel, Deewar Mein Khidki Rehtee Thee. He makes conjugal love interesting and unique, by interpolating it with fantasy. But he steers clear of erotica; otherwise his fate might have been the same as mine.

We can safely say the current moral slogan in Indian society is “beware of erotica and absolutely no questioning of the value system”. If you dare to break the social taboo and fall in love with a member belonging to a different religion, beware of uttering the word “marriage”. Remember that in our parlance, it is “Love Jihad”. We, Indians of the 21st century condemn both love and jihad as attempts to think for ourselves, hence is immoral. It is doubly so when women dare to indulge in it.