On August 05, 2019, while the central government’s decision to abrogate the semi autonomy of Kashmir was celebrated across the television screens by the national media, Kashmir faced a total communication blackout. While the majority of the news channels aired joyous processions carried across the streets in hailing the government, the roads in Kashmir were laced with barbed wires and decorated with curfew arrangements. The contrasting images made me ask a string of questions, one leading to another. First, why is the reception of the government’s decision so starkly different between people residing a few hundred kilometres across? Why is a mother/father’s failed call to her daughter or son cheered by another daughter/son? Why do Indians (in majority) react to the Kashmir conundrum in the way they do? Is this because of the way Indians growing in the post-colonial India are taught about Kashmir, India and their intertwined history? Perhaps yes.

Prof. Romila Thapar explains that the history that was written in post-colonial India carried the unquestioned nationalist tint because of which some critical questions could not be focused upon. Perhaps the way history was periodised has a role to play, because it affects the way we imagine the past. This essay pauses for a moment to ask for a re-examination of the periodisation that informs intrinsically both Kashmir’s and India’s history. Furthermore, it questions how the generations that grew up in postcolonial India would respond to the Kashmir conundrum if they were taught a different view of Kashmir’s history. To add to that, how would it affect the contemporary Kashmiri populace?

Ever since the publication of James Mill’s The History of British India, the concept of periodisation assumed importance in Indian History scholarship. Mill divided Indian history chronologically into three parts, the Hindu India, the Muslim India and the British India. These were initially accepted by all including the nationalists. In the post Independence period, Thapar points out that historians rejected Mill’s periodisation and opted to classify Indian history into three periods viz ancient, medieval and modern. She continues that although the labels did change, the time periods that Mill classified did not. It meant that Hindu India subsequently became ancient India and the order followed. This, she claims “was no(t) real change and we were back to square one.” Therefore neither did the European way of categorisation of history change, nor did the communal undertone.

The same method was also adopted to look into Kashmir, both by the British and subsequently by the Indian academia. Popular historical narrative and scholarship of Kashmir includes an ancient Hindu era from the time of Nilmanta Purana to the arrival of Islam in Kashmir close to 13th century, then a Muslim medieval era, ultimately to a Modern era that begins roughly with the Sikh regime and continues under the suzerainty of the British empire (incuding the formation of the Princely state of Jammu and Kashmir) till date.

Such periodisation often offers a blanket imagination of the past. Michelguglielmo Torri points out that periods based on the religion of the ruler might often mislead both the present and shroud the past. He explains that in the case of India such categorisations have often painted the Islamic rule as alien/invaders and Britishers as saviours. An idea that plagues the political imagination of India till date. In the case of Kashmir the arrival of Islam in the courts did not permanently push the Hindus especially-priestly class and the Buddhists out of public life as historian Hassan testifies. However, this Hindu-Muslim binary often obscures the Central Asian roots of Kashmir. It often underrepresents the importance of the pre-colonial long distance trade economy that Kashmir was a part of due to its presence within the Silk Routes.

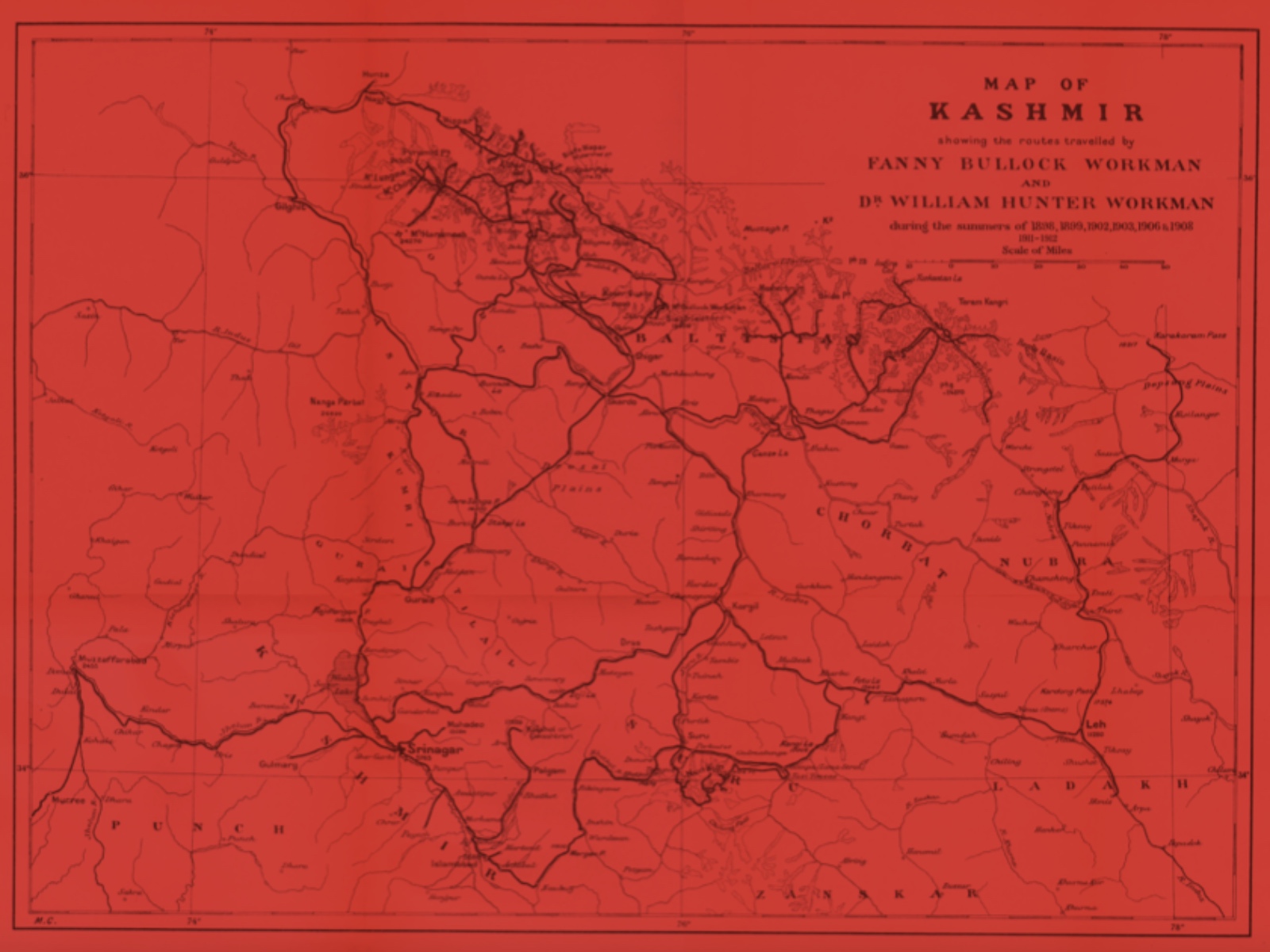

The trade network resulted in both inflow and outflow of people to and from Kashmir within Central Asia. It connected the regions such as Tibet, Yarkand, Kashgar in the east and to cities like Merv and Bukhara in the west. In addition, irrespective of the ruler and his religion, traders played an important diplomatic role between Kashmir, Lashak and other Central Asian regions. For example, Haji Mohammed Siddiq, a Kashmiri Mulsim was entrusted by the Buddhist King of Ladakh with the Lopchak Mission to the Dalai Lama in Tibbet. This mission included gifts sent as tribute by the Buddhist monarch to their highest religious leader.

There were multiple travellers’ inn that embodied a melting pot of different Central Asian cultures and one such inn standing till date is the Yarkand Sarai. It was also the network through which the much famed Kashmiri Pashmina shawl travelled to distant parts of the globe, from Paris to Egypt. However, the current mainstream historical narrative offers little room to understand these aspects of the Kashmiri history.

The current points of ruptures also fail to address the cause of the collapse of these trading roots. Elsewhere I have mentioned how the arrival of colonialism changed the way of looking into Kashmir as a region and the idea of frontier or borderland was imposed. British travellers and officials sent on missions in Central Asia, though mention the presence of a trade economy but fail to underscore the commercial importance of it. Rather the descriptions were overtaken by suspicion and uncertainty of the ‘frontiers’. Under the Dogra regime British India looked upon the traders with suspicion and mistrust for their years spent on caravans near the Central Asian Khanates, which the colonial government considered as a buffer zone against the expanding Russians. Another point that John Bray highlights is the inability of the Britishers to understand the diplomatic functions of the traders. A problem similar to that faced in Afghanistan. Its influence in the British foreign policy, coupled with hasty cartographic division of the territory made the trading network suffer one of the heaviest blows, and its impact on the Kashmiri society is yet to be properly studied. On the other hand, whatever the travellers recorded and was preserved by the colonial rule later became the source of history and knowledge production. The lack in the representation of this aspect of the Kashmiri society can perhaps be understood in this light.

Finally, since the reason behind periodisation is to give clearer context to events recorded in the past, therefore, imposition of periods from the top or by the rulers might result in flawed knowledge production and can adversely impact the generations of people whose history is produced. On the other hand, periodisation based on the notion of the locals’ sense of history perhaps could potentially change the way generations have reacted to such histories.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot in his book Silencing the Past masterfully portrays how micro events of the pasts often, shrouded by other contemporary events, give history a different outlook. Painting an image of the past that invariably continued and still continues to help the invisible power of the time. Trouillot also points out that places having potential to narrate important historical traditions are often pushed towards obscurity by dominant historical narratives.

The region of Kashmir has always been looked either with the idea of borderlands, security and international relations, or with the established Indocentric view of an ancient Hindu past continuing into a period of Islamic era and finally into an era of chaos and it is important to question both these notions, along with their identified points of rupture.