The memes about the pandemic are really hilarious. It is a fun way to spread awareness. However, one such meme made me think beyond its comic interpretation. The image depicts a scene from the Hindu epic of Ramayana where one wrong move of ‘crossing the line’ by the female protagonist Sita, disobeying her brother-in-law Lakshman resulted in her abduction and a war which followed between the so called male protagonist Ram and the antagonist Ravan. The caption reminded us of what happened to Sita when she crossed the line, drawing an analogy with the current situation. “Stay home, Stay Safe.” What looks like a comic representation of the pandemic situation tends to become unsettling, if the usage of the image of a woman bound in the peripheries of home and ‘not crossing the line’ is considered, given the historic evolution of such a process.

The construction and functioning of a patriarchal world order dates back to time immemorial, as one may argue. However, the patriarchal setup as witnessed in the contemporary order, has its immanent roots in the capitalist structure of the society. At the first instance, one may fail to understand the intrinsic link between capitalism and the tailored idea of a ‘woman’. The idea of a ‘woman’, a mere identity categorising an entire sex, in no way appeared out of mere abstarction. The identity, its specific roles, its confinement, its invisibilisation are all products of societal constructs, and one may argue, indirectly, of capitalism, which marked the departure from a feudal society to a market-oriented one.

Enclosures in Capitalism: Enclosing the Idea of a ‘Woman’

The ‘transition’ from feudal societies to capitalist ones, was that of enclosures and evictions. Enclosures of land as private property and eviction of farmers from their communal land. What sits at the core of a capitalist structure is the creation of forced labour (or wage labourers) through the process of eviction and private property rights. Marx, in this regard writes, “The capitalist system pre-supposes the complete separation of the laborers from all property in the means by which they can realize their labor. As soon as capitalist production is once on its own legs, it not only maintains this separation, but reproduces it on a continually extending scale.” The second foundation on which capitalism sustains itself is the reserve army of industrial labour, wherein an excess, unemployed workforce is maintained at all times to keep the wages of labourers low. These processes have an everlasting impact on the creation of gender roles, witnessed through the discordant historical process of transition.

Federici provides a perturbing and an unsettling insight into the historical episodes in medieval Europe in her work, Caliban and the Witch, noting how women were transitioned into commodities for production and consumption in the process of primitive accumulation. To understand the transition of ‘women’ into commodities, it is important to account for the transition of the males in the feudal societies to wage labourers. Through enclosures and the imposition of private property rights, the farmers were coerced and criminalised out of their means of subsistence, to become wage labourers, serving the interest of the capitalist market, and were now ‘free’. This transition from subsistence to ‘freedom’ not only reduced the male workforce to a state of acute immiseration, it led to the exacerbation of the miseries of their female counterparts left behind.

It has to be taken into consideration that women, before the advent of a capitalist society were not in an exalted position of any sort. However, given the capitalist structure, their roles were renegotiated and tailored to fit the robe of capitalist accumulation, surplus value generation and serve its purposes of labour production. The role of a woman was now confined to reproduction and familial activities to oil the wheels of capitalism. This can be considered as the first stage of their confinement. The second stage of confinement was marked by the reduction of women as objects of sexaul pleasure, consumed as mere commodities, to cater for the needs of the bourgeoisie and proletariat men. Thus their commodification was complete. What is germane to note here is the fact that women are of strategic importance to capitalism, in terms of both production and consumption. The production side is related to the gift of reproduction that women hold, which, within the capitalist system, is means of production, of more labour and capitalism fundamentally aims at the control of all means of production. Therefore, the capitalist control of women’s womb, of reproduction, becomes germane for the perpetuation of the capitalist structure. On the consumption side, the commodification of women as sexual objects is beneficial to men of all kinds, without any class divisions,

This process of creating the gendered notion of a woman, for the indirect control of her womb as means of production, rather reproduction was marked by the creation of an affixed identity of a ‘good woman’ as a mother, a child rearer, a caregiver, as a domesticated object, protected by the male breadwinner, confined to the private domain of preservation. For the ‘good woman’ to exist, the ‘bad woman’ had to be created. If one were to critically look at the common folktales and bedtime stories, (Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, Snow White etc.), a commonly recurring theme is that of a witch, or an evil stepmother and a damsel in distress. It can be asserted that the folktales emerging in the medieval European setting was a reflection of the societal order, which was marked with increasing incidents of witch hunting. The creation of the idea of a “bad woman’, a witch and the concept of witch-hunting was indeed strategically imagined, to further degrade the position of women. Any woman with agency, with an individual identity, taking charge of her own body, her own womb, standing against the agonising arrangement of the society was associated with that of an ill-omen. Hence, the identity of a ‘good woman’ was created, through her domestication, and a ‘bad woman’ was identified through her resistance against capitalist patriarchy.

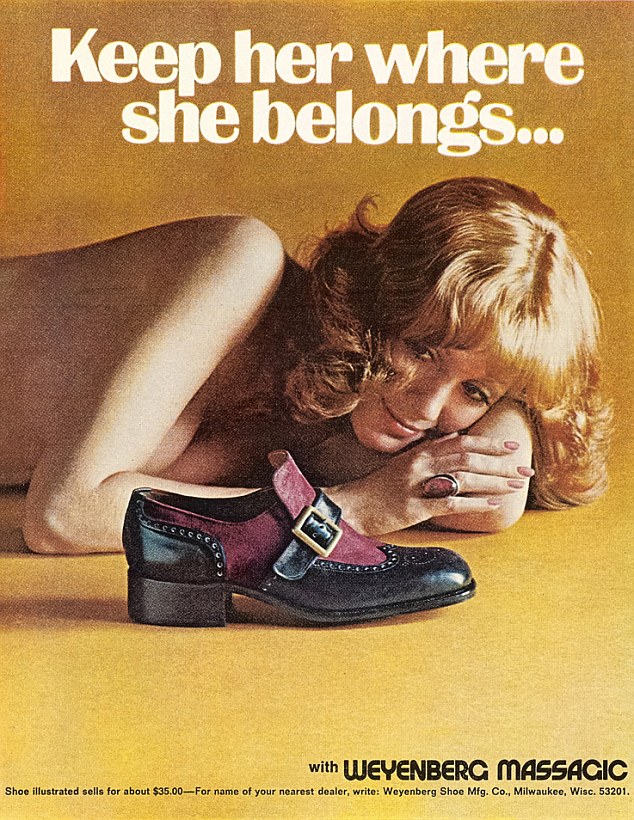

This confinement has evolved, through the market which exploits and reiterates this notion for the convenience of profit. The advertisements for consumer and household goods in America in the ‘60s and ‘70s, presented women as the epicentre of the advertisements. As Mies observes, it served a dual purpose on which capitalism thrives, the generation of consumer demand through the objectification of women and the promotion of the idea of Mrs. Consumer, confined to their domestic sphere.

India and her Dayaans

If Europe has witnessed the making of a witch, India continues to categorise her women as Daayans, with their feet inverted. The inverted feet made me delve into its possible symbolism. To domesticate a woman, controlling her womb is not enough. Her feet, which take her places, need to be controlled first. Those feet which remain home, serve the purpose of capitalism. In the Indian context, the existence of caste hierarchy in Hinduism has only abetted the proliferation of capitalism. Dr Ambedkar opined that caste is an enclosed class, enclosed through endogamy. The prevalence of a caste system has not only fostered capitalist accumulation in the caste hierarchy, it has also abetted the patriarchal order through the confinement of women through the confinement and removal of the ‘surplus woman’ either through Sati or the imposition of widowhood. Subjugation and the creation of good and bad women can be witnessed in the Hindu mythological texts, the characters of Sita and Surpanakha, for instance.

Therefore, the image here is not a mere object of entertainment or awareness. It silently speaks of the intersection between capitalism and patriarchy. The idea of ‘disobedience’ or ‘crossing the line’ which the image portrays is symbolic of their confinement, to cater to the needs of the men who provide them with food and shelter, to reproduce for the capitalist economy to flourish. It is symbolic of them being ripped off of their agency, their identity.