Insurgency means to ‘rise up against established authority’, but not necessarily with arms. To be insurgent is to resist an established order. How then, can a Constitution be insurgent? Does a Constitution not establish an order? Yes, generally a Constitution is a set of principles that legitimizes a new order. However, it would be a mistake to read the Indian Constitution as expressing a singular will and a singular order.

The pathalgadi movement in the tribal belt across Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Odisha; reveals how the constitution can operate as an insurgent document, offering movements and the resources to think in radically transformative terms.

Pathalgadi

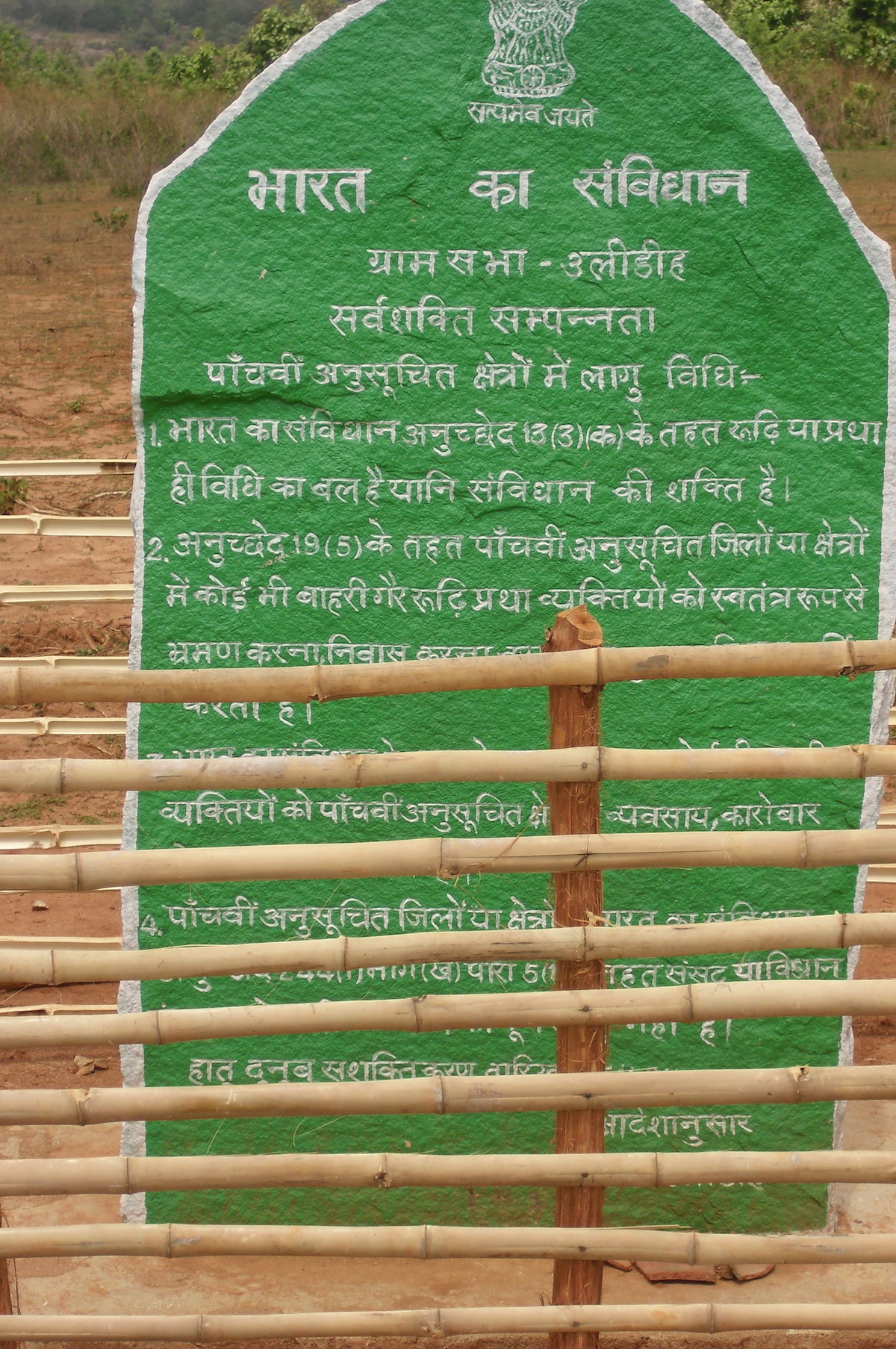

Sweeping across the tribal belt of the states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Odisha since early 2018, is a movement in which the adivasis have reworked a tradition of putting up stone slabs to honour their dead (pathalgadi). These stone slabs now assert their sovereignty over their lands. The pathalgadi revolution is capturing the imagination of village after village, and wherever these giant green painted stones stand, the movement declares, marks the limit of entry to government officials.

Inscribed on these stone slabs are messages of self government, but where do they draw their legitimacy from? They claim legitimacy from the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA), from which these words inscribed on many of the stones are taken:

‘every village shall have a gram sabha (village council)…and every gram sabha shall be competent to safeguard and preserve the traditions and customs of the people, their cultural identity, community resources, and the customary mode of dispute resolution.’

The Indian Constitution is not a document that has managed to establish one unitary order. It reflects a variety of political opinions from Left to Right, emerging from a mass anti-imperialist struggle, and therefore tried to balance individual and community, equality and special provisions for historically disadvantaged groups, the drive towards industrialization and rights of the peasantry.

In other parts of the region, the stones directly invoke the Constitution, in which collective ownership of tribal lands is protected by the Fifth Schedule and other specific Articles. Seventy years of independence have brought tribal people nothing but exploitation and neglect, and these regions have been in ferment for decades, but the immediate trigger for the pathalgadi movement can be traced to 2016, when amendments were proposed by the current BJP government of Jharkhand, to two key legislations that protect tribal rights to their land. The legislation was passed, but aroused such widespread opposition that it had to be withdrawn. Subsequently, the same effect has been achieved by the BJP government by the passing of amendments to another legislation in 2017, that is, the Land Acquisition Act, 2013. The amendments enable the acquisition of tribal land for ‘development’, reduces the scope for social impact assessment and reduces the powers of the gram sabha to merely giving ‘advice’. This legislation received the assent of the Governor this year, in 2018. What is more, the copy of the Amendment Bill, which finally got the assent of the President, has been kept out of public circulation by the government, and what can be viewed is only the Draft Bill.

All of this has aroused deep anger, exacerbated by the kinds of methods state agencies use to discredit the movement. But the expression of this anger is through the assertion of supremacy of the Indian Constitution, while the government in power has, in letter and spirit, eroded its provisions.

Several leaders of the pathalgadi movement – who include former senior bureaucrats – have been arrested under charges of sedition. The movement faces the full might of state repression. However, a second rung of leadership has emerged, and the movement appears to be gaining strength, discussing the setting up of an Adivasi Educational Board, an Adivasi bank, and such institutions, through public meetings held under trees (Sundar 2018; Tewary 2018).

Pathalgadi is one example of insurgent constitutionalism among others like the campaign against Section 377 that criminalized same sex desire; and the Campaign for the Right to Information. The Indian Constitution is not a document that has managed to establish one unitary order. It reflects a variety of political opinions from Left to Right, emerging from a mass anti-imperialist struggle, and therefore tried to balance individual and community, equality and special provisions for historically disadvantaged groups, the drive towards industrialization and rights of the peasantry.

If it was meant to legitimize the brahminical, patriarchal, class society that India is, it certainly failed, for it ended up reflecting the heterogeneity of impulses of the anti-imperialist moment. It ended up therefore, being a porous document with one foot in the future. This is a very different moment in time and space from that which produced the constitutions of the West, which in a sense marked a closure of, and an end to political ferment. The Indian Constitution is seen by all participants as the beginning of a journey towards what the preamble promised.

Reassertion of the Constitution against Hindu rashtra/nation

The Hindu right-wing government in power since 2014, has de facto established a Hindu Nation in which minorities and Dalits, as well as dissident voices even from within the Hindu community, are terrorized, killed. Diktats on whom to love, what to eat, targeted lynchings and assassinations, have all become the norm. Through all of this, gradually, voices of dissent to neoliberal policies and brazen crony capitalism as well as to Hindu rashtra, have arisen from different sections of society – Dalits, whom the Hindu rashtra is incapable of accommodating or recognizing, students, farmers, artists, scientists, academics. The Constitution is a banner of revolt for many of these movements.

The Indian Constitution turns out not to be a simple seal of legitimacy on ruling dispensations of caste, class and gender.

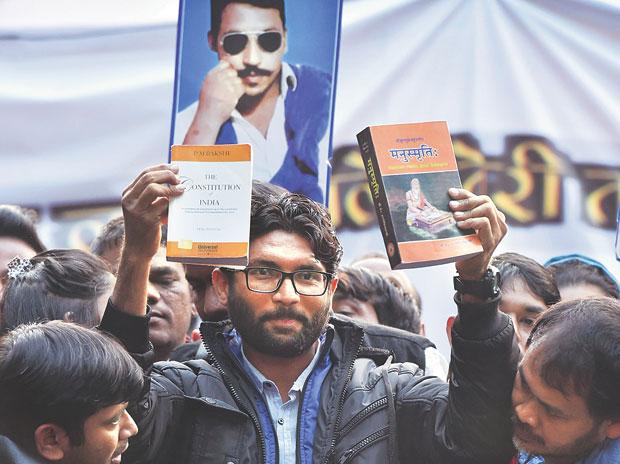

For instance Jignesh Mevani, charismatic young Dalit leader and now a member of the Gujarat state legislature, directly counterposes the Constitution to Manusmriti, the ancient text that sets out the hierarchical caste system. When he does so, he is drawing on the insurgent possibilities in the Constitution.

As does Chandrashekhar Azad, founder of Bhim Army, a mass social movement for dignity for Dalits. Azad has been jailed several times, including under the draconian NSA. At his meetings, attended by thousands of Dalit youth, he routinely holds up a Hindi copy of the Constitution.

His proud moustache, his dark glasses, are themselves a direct performative challenge to the vicious caste system in which Dalit men have been physically attacked and humiliated for daring to grow moustaches or ride a horse to their weddings as upper castes do.

Maya Rao’s performance at the Women’s March (April 2019), where she first symbolically strips, then re-clothes herself with the values of the Preamble to the Constitution – equality, liberty, fraternity…

The Indian Constitution turns out not to be a simple seal of legitimacy on ruling dispensations of caste, class and gender. It is a document that emerged from the acute conflicts and contestations in the anticolonial struggle outside, and from the contentious debates inside the Constituent Assembly. Its vision therefore, was never singular. Rather, it became something of a manifesto of a future state of affairs, where the ethos of egalitarianism would be decisive.