Today, September 10, is World Suicide Prevention Day.

In popular cinema which is brazenly targeted at mass consumption, suicide, especially when committed by female characters, has the potential of making use of cinematic clichés that have evolved into stereotypical cinematic codes. The modus operandi remains restricted within a few means such as a dagger thrust into the abdomen as done by Zaheeda in Anokhi Raat (1968) by Calcutta’s Asit Sen. She kills herself surviving a gang-rape, because she considers it a “violation of her body”.

Death by hanging has been a common mode used by characters in many so-called “masala” films. However, the most common scene has been that of a small bottle labelled “poison” laying aside the dead body’s open fist. A suicide note left behind however, may often imply the opposite — a murder faked as a suicide, where the letter has been signed by the signatory at gunpoint. Atmospheric effects such as bizarre and loud lighting, repeatedly used masked shots of legs dangling from an off-scene ceiling fan, a close-up of an open fist with the poison bottle, aided and abetted by a melodramatic sound track of stock music form the mis-en-scene of a cinematic suicide. There is no pretension to aesthetics or to attaining high standards of cinematic excellence — mood lighting, imaginative sound effects, a moving background music score, brisk cutting, aesthetically balanced superimpositions, wipes or fade-outs. Today, the signs are so much a part of the mainstream that they are anticipated a priori by the audience, which rarely goes wrong.

Suicide often sets one on an introspective journey into one’s own past when someone we know destroyed themselves. How would we react to the suicide of a young girl in the neighbourhood? Perhaps, with a “thank God its not me” attitude, and then perhaps, a little superficial introspection. The next day, life is back to normal. This forms the central idea of Basu Chatterjee’s Kamla ki Maut (1990). Based on a short story by Swadesh Bandopadhyay published in Sarika in the early 1970’s, the film opens with the death of a young girl, Kamla, (Kavita Thakur) who has just discovered that she is pregnant and her boyfriend has jilted her. She jumps into the central compound of the chawl they live in, to the voyeuristic horror of the chawl neighbours. Instead of dwelling on the buzzing of the grapevine after the incident, Chatterjee follows the reactions of one family, an old man, Sudhakar, his wife Nirmala, their young daughters Geeta and Charu. They discuss the suicide nonchalantly over hot cups of tea with battered onion puffs. “Why did she have to jump into the building compound in broad daylight?” says Nirmala insensitively, adding, “there are other ways of committing suicide.”

In terms of social relevance, Kamla Ki Maut is a significant statement on the impact of a young girl’s suicide on the urban middle-class, the class she belongs to. It gently points out the tragi-comic ironies of life and encourages the viewer to laugh at them. But is suicide really a matter to laugh at, even when shown on film? The movie remains memorable because of its subtle underpinning of three important facts of life — the futility of death, the futility of guilt and perhaps, the futility of love too.

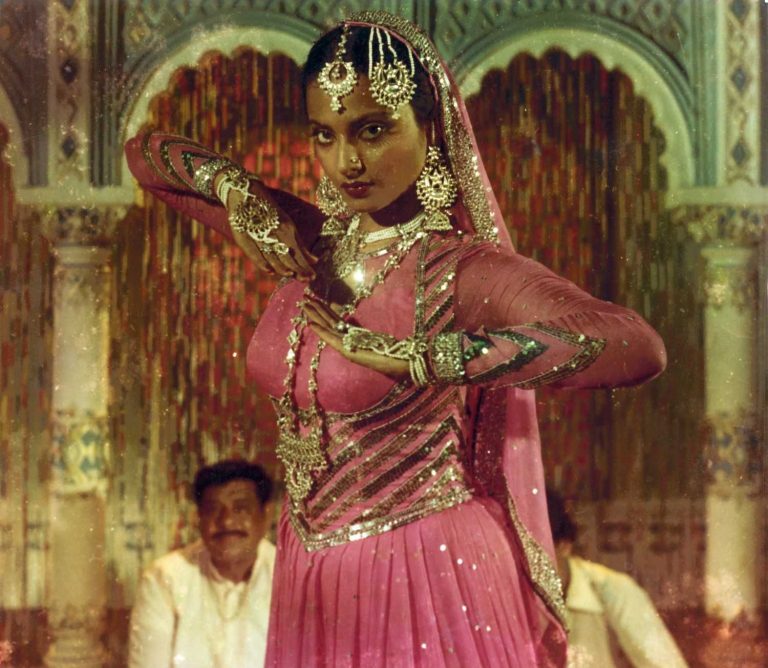

In Prakash Mehra’s Muqaddar Ka Sikandar (1978), courtesan Zohrabai (Rekha) falls in love with a rags-to-riches orphan hero Sikandar (Amitabh Bachchan) who is in love with Kaamna (Rakhee Gulzar) instead, the beautiful daughter of his one-time employer. Zohrabai knows that Sikandar does not love her, but as a strange form of commitment to her love, she quits her profession and shuts the doors of the kotha to her business. This reinforces the masculine will ruling society, permitting only marginalised women to enact romantic love, precisely because it does not reach fruition. When Zohra finds the pressures of surrendering to the villain, she commits suicide by sucking on her diamond ring. Director Prakash Mehra treats her suicide like a celebration of unrequited love, absolving Zohrabai of the stigma of being a kothewalli through death.

Chaudhvin ka Chand (1960) is based on Saghir Usmani’s story. Basically a story of male bonding woven into a tale of three friends, it culminates into a love story where two of them, Nawab (Rehman) and Aslam (Guru Dutt), fall in love with the same woman, Jameela (Waheeda Rehman), albeit distanced in terms of time, circumstance and social context. In a case of tragic mistaken identity because of the veil on the woman’s face, Aslam marries Jameela in an arranged match and falls in love with her. When he learns that this is the same girl Nawab is searching for, he sets out on a journey of sacrifice. He frequents prostitutes in the hope that Jameela will reject him and marry Nawab. When Nawab learns why Aslam is paving the way for self-destruction, he swallows a diamond ring and dies. Though apparently designed to emphasise the value attached to male bonding through friendship, Nawab’s suicide raises a nagging question — was the suicide really to uphold friendship or was it the price Nawab paid for his hurt ego? Or was he punishing himself for failing to have the ethereal beauty that Jameela was as his wife?

Parasuicide is primarily a cry for help. Young lovers in films like Ek Duuje ke Liye (1981), Noorie (1979) and Qayamat se Qayamat Tak (1988) adopt this form subconsciously, without being aware of the fact that their joint suicide pact is really a cry for help to be noticed. Sociologically, parasuicides are seen among the young, whereas “genuine” attempts with those aged between the 55-65. According to Anisul Haque, these films portray a revival of romance set in the ‘80s. Films centered on youngsters were the rage and were seemingly honest, sentimental presentations of the nation’s youth.

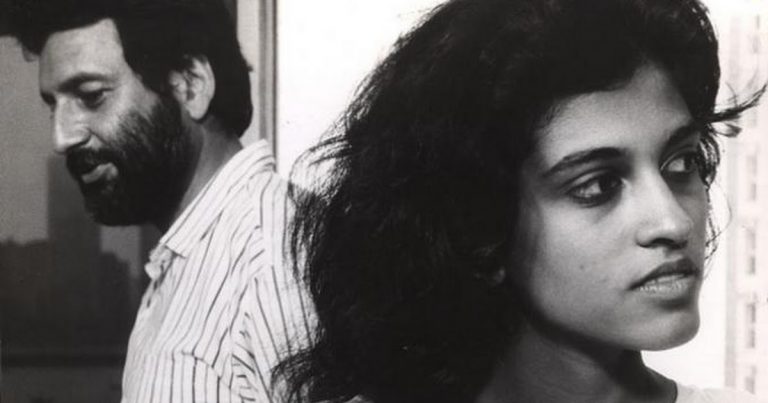

This suicide of “protest” came lucidly through in Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s Andhi Galli (1984). The story of Hemant (Kulbhushan Kharbanda) and his new bride Jaya (Deepti Naval), it shows a naive and innocent woman unaware of the complexities of life in Bombay. Hemanta, who is trying to make it in advertising, suddenly becomes aware of his wife’s potential as a model. Jaya, more surprised than happy, is shocked when after a point, she is asked to strip for a campaign rooted in a rural setting. Hemanta flares up and Jaya is shocked at discovering that her husband is prepared to put his wife up for display against her wishes for money. She jumps off the balcony of a skyscraper, as her way of crying out against the moral decadence of her husband and against the city which, to her, is no wider than a blind alley (Andhi Galli) offering a one-way ticket to death.

The suicide of young Amina in M.S. Sathyu’s Garm Hava (1975) too contains shades of a Freudian suicide. Amina (Gita Siddharth) is in love and engaged to Kazim, but he is forced to go away with his parents to Pakistan. When Kazim clandestinely returns to marry Amina, the police arrest him. Following this, the family tries to strike a negotiation between Amina and cousin Shamsad (Jalal Agha). Reluctantly, she drifts into a relationship with him, but as she warms up to his advances, he too leaves for Pakistan. The strain on the family’s finances as a result of her father doggedly deciding to stay back and the emotional dread of having to leave any time bears down on the girl. In the secrecy of her room, Amina decks herself up as a bride and quietly slashes her wrists. The film contains a moving shot where Amina slowly picks up her love letters one by one and throws them to the wind. She watches their journey as they drift in the breeze, her face bearing the semblance of a wistful smile.

Mani Kaul’s film Nazar (1990) is loosely adapted from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s short story, The Meek One. It is about a girl who enters into a relationship with a pawnshop owner, a man who has his own past traumas. The two want to make contact, yet each one cannot, as if modern living has shaped the destiny of love being impossible to experience. The chasm continues after they get married. The girl, whose relationship with her elderly husband is captured only through glances finally walks out of the relationship. She steps out of the balcony as if she is stepping out for a walk — her suicide, out of the frame, is shown in the same pace as the rest of the film. It is a natural continuity and an extension of the relationship in the film. However, we are encouraged not to see the suicide as an easy escape. The suicide may have been imagined and it might not have happened at all. Taking us beyond the confines of the story, Kaul prods us to reflect on the human condition rather than to reach precise conclusions.

Mrinal Sen’s Mahaprithibi (1991) begins with the suicide of the mother of a joint family. The members of the family feel the secret of the suicide is locked in the pages of her diary. But none of them can really get down to read it. This, however, is not one of Sen’s good films though Sen succeeded in investing the film with the mood, the ambience and the gloom of Death which persisted till the end of the film, offering no reprieve. Linking the whole narrative to the unification of Germany was so far-fetched and unrealistic that Mahaprithibi just failed to work as a film.