Indian Cinema, with its wide range of audiences, is closely knit with other forms of culture, such as theatre, literature, and television, helping project a commonsensical, consensual view of history.

Period films are not products of directors who are historians manqués, but commercial film-makers aiming to reach the widest audiences through cinema. While historical research is important, the commercial format and requirements of the film are dominant.

British historian Alex von Tunzelmann in her book, Reel History: The World According to Movies, writes that a “lot of people can and do believe some of the things they see in the movies”. It creates a new narration which becomes factual for some, especially among children and others less likely to do some amount of fact-checking on their own.

One of my friends from Nepal, fascinated by Indian history and period films based on it, has told me how she believes in the romantic saga of Jodha-Akbar and Saleem-Anarkali. She supports her beliefs with all of this is portrayed in Indian cinema and television.

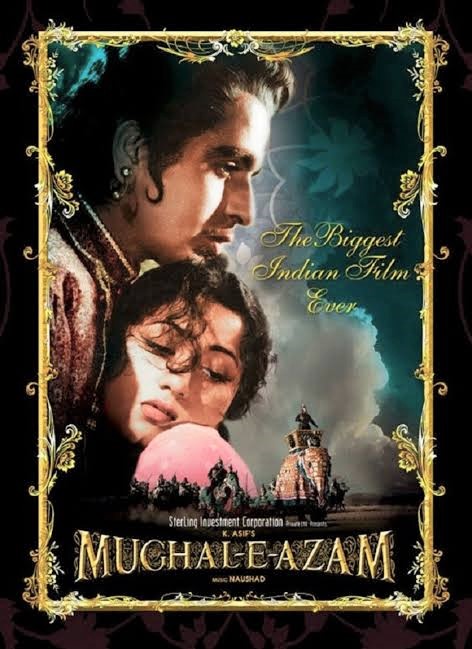

This is not new. If we trace back the trend, the film Mughal-e-Azam (1960), depicting the love story between Mughal prince Saleem and Anarkali, a courtesan, which is based on local legends, has become history for many common Indians. There is no reference to any lady by the name Anarkali in historical texts like Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, the autobiography of Prince Saleem, also known as Jahangir, which he penned from 1605 to 1622. The film portrays Prince Saleem as a humble son to his mother and a gentle lover, while Abu’l Fazl, author of the Akbarnama1 , gives a different picture of the man, who mentions several instances of countless cruel acts by Jahangir upon those around him. The narrative of Prince Saleem as a committed lover to Anarkali, who was bound by his father, is different from what is found in many historical texts.

When juxtaposed with historical texts, the character of Saleem is quite misrepresented in the film. He considers his father as an enemy of love and refuses to return Anarkali to the Emperor in exchange for his pardon even when on trial for rebelling against the throne. As Anarkali faces her punishment, Saleem declares no claim for the throne and delivers a powerful monologue:

“Then the Emperor should also punish moths who sacrifice themselves onto the flame.

He should imprison honeybees that hover around flowers, singing love songs. Stop rivers that rush to lose themselves in the sea’s embrace.”

All of this, when even the mere existence of Anarkali has been questioned by historians.

The portrayal of “Jodha Bai” as the Hindu wife of Akbar is also contested, but many films and television series are based on the myth simply because it appeals to the emotions of the public at large, while asserting that Jodha and Anarkali were real-life characters in Indian history.

Vasav Dutta Sarkar, a Delhi-based history teacher says,“Movies have a big impact on school students and misrepresenting history can lead to confusion.”

The 2001 film Ashoka, based on the life of the emperor from the Mauryan Dynasty too is quite different from historical facts. The portrayal of romantic relations between Pawan-Kaurwaki has no historical affirmation. There is also no historical evidence for a queen ruling Kalinga at the time of Asoka’s invasion and the film also explicitly suggests Kalinga as a democracy though the film does not claim to be a complete historical account of the life of Ashoka and is riddled with historical inaccuracies, but many students confuse the movie for historical facts in classrooms”, adds Dutta.

Indian period films have not only played with the facts and myths of history but also play a huge role in adding emotional values to particular characters, communities, and societies. Through the re-enactment of history on the silver screen, it plays with the psyche of the Indian audience, making them believe that they are witnessing the actual past. These alterations in the facts of history create alternate narratives.

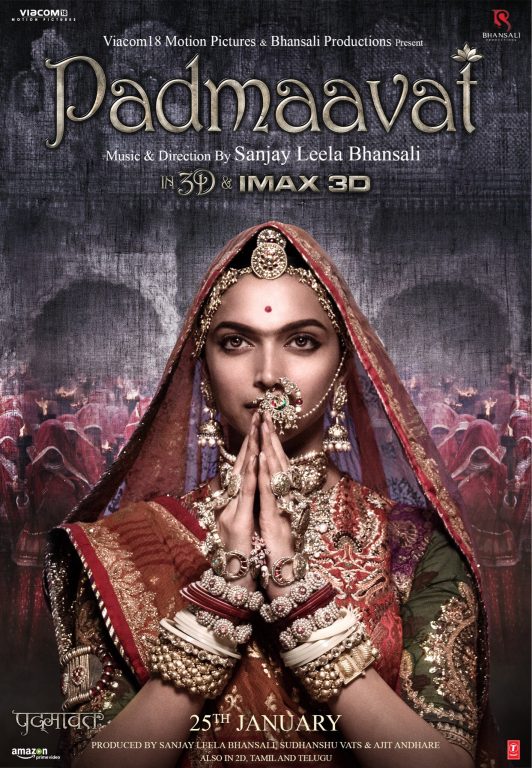

In Padmavat (2018), which is an adaption of the epic poem “Padmavat” written in 1540 by Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi, tries to make people believe in the existence of a Queen Padmavati, along with many other historical inaccuracies. While on the one side, the existence of Queen Padmavati is still debated by historians, on the other hand, the portrayal of Allaudin Khilji is mired in ambiguity.

According to historian Rana Safvi, Khilji was a patient, sophisticated man capable of planning and organisation, as opposed to how he is portrayed in the film, as a barbarian tearing into meat.

In the film, the flag of the Delhi Sultanate is shown in green colour with a white crescent moon, but the Sultanate’s flag in reality is said to have been green with a black band running vertically on the left.

The portrayal of Khilji and Jalalluddin somewhere appeals to the average Indian and makes them believe that a specific community is cruel and exploiting, in contrast to the other community, which seems to hold higher moral values and principles.

The epic is based on the Sufi philosophies of “annihilation of self” and “Ishq-e-haqeeqi” or love for the divine, but the film kills the spiritual core of the epic on which the film is supposedly based. The filmmaker has used Hazrat Amir Khusro’s famous verse to project Alauddin’s obsession for Padmavati that was, according to the film, driven by ego and lust.

“Khusrau darya prem ka, ulti wa ki dhaar, Jo utra so doob gaya, jo dooba so paar.”

(“Oh Khusro, the river of love is such that it runs in a strange way,

One who jumps into it drowns, while one who drowns in it, reaches the other side”)

Popular history, promoted by cinema, dominates a great part of academic history in India, primarily because everybody is not a historian or even makes an attempt to get their facts right. A majority of the public accept what is served to them through cinema. The filmmaker’s right to “creative freedom” becomes a burden for academicians. It creates a political culture where debate is largely formed by appeals to the emotions of the public at large and fairly disconnected from the details of history, where factual rebuttals are ignored.

In present times, where intolerance is at its peak, the pride for religion, heritage, culture dominates the love of the nation and underlines the dichotomy between nationalism and communalism. Such a post-truth trend by Indian cinema has blurred the boundaries between fact and fiction. These blurred boundaries have also contributed to the problems that will have severe implications.

1. Fazl, Abu’l. Akbarnama:Ain-i-Akbari. Translated by H. Beveridge. Vol. 3. Calcutta:Asiatic Society, 2004. 1088.