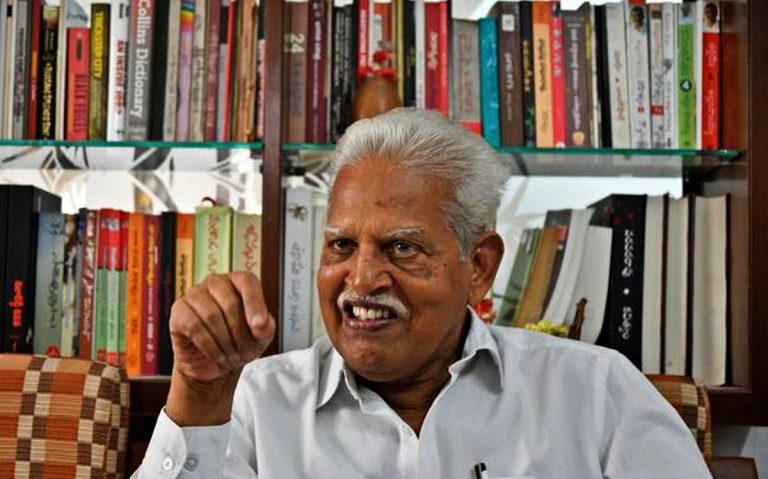

I wouldn’t have been who I am without Varavara Rao, and it is true for the generation I come from and the one that followed. Today’s Telangana wouldn’t have been what it is without him. I have written and spoken about him and his poetry in the past, but now he is on the deathbed, in a faraway hospital, being subjected to retributive torture by the powers that be. Now, with a never-before urgency, I want to speak and write about him, through an interminable torrent of words.

Here, I will attempt to paint the 80 years of his life in seven angles — a rainbow of seven colours that characterise him — a creative writer, teacher, editor, organiser, activist, and lastly, a victim of the state, yet a humane individual.

Part 4

I’ve always felt that Varavara Rao had a magnetic personality, which would attract not only those who would agree with him, but also those who didn’t. This must be why it doesn’t feel superfluous to say that he can provoke a flurry of thoughts in anyone who listens to him speak. In the past 60 years, from when he was 17 years old and the Secretary of a Telugu literary forum in college, to today’s Bhima Koregaon case, VV has tirelessly engaged himself in organising people and building movements.

VV did not become part of any particular organisation, but he actively took up organisational activities and engaged in facilitating them. It’s not at all surprising then that in 1958, he was the first convenor of Mitramandali (simply translated, a group of friends), which met every week to discuss literature. The group was started by poets and activists Kaloji Rameswara Rao and Narayana Rao, who saw VV from a closer proximity and recognised his skills to bring people together for a cause. Later, at Osmania University, VV played a significant role in bringing out a poetry collection titled Raatri (Night), meant to tear asunder the stillness that confronted the socio-political and literary scenario of the time.

Also Read: The Making of Varavara Rao: Parts Two & Three

In 1969, he moved to Warangal from Jadcherla and became the leader of a group of poets who called themselves “tirugabadu” (rebels) — the same “rebel” writers who formed the Revolutionary Writers’ Association (Virasam) a year later in 1970. VV was the major driving force of Virasam not only at its inception but also for the next fifty years of its existence. A working committee member of the Association for the 40 years following its formation, VV stepped down with a wish for members of the younger generation to replace him. He, however, continued to give guidance to its publications and also brought out many valuable books under Srjana Publications. He worked as the Editor of Arunataara (Red Star) and the Secretary of the organisation for a while, and also played an important role in many revolutionary publishing houses like the Sramikavarga Prachuranalu (Proletariat Publications).

There have been some significant milestones in VV’s life as an organisation builder. Directly or indirectly, VV has influenced major revolutionary organisations of the Telugu land for the last 50 years, including the Jana Natya Mandali, AP Civil Liberties Committee, Bharat – China Mitramandali, Radical Students Union, to name a few. Alongside, he was the founder and mentor of organisations like the All India League for Revolutionary Culture (1983), All India People’s Resistance Forum (1992), Revolutionary Democratic Front (2005), and others.

In 2002 and 2004, when the Andhra Pradesh High Court mooted the idea of talks between the government and the revolutionary parties to usher in peace, the Committee of Concerned Citizens took up the responsibility of bringing both the parties to the negotiating table. It was VV who acted as an emissary representing the revolutionary parties during these talks, during preliminary attempts in 2002, and later in 2004, during the actual talks. In fact, his several attempts to ensure the rule of law and to bring the excesses of police and state to the notice of the judiciary must be remembered along with this.

Although severely criticised for his revolutionary literary activism and for being a staunch sympathiser of the revolutionary movement, VV remained consistent and dedicated to the path he believed in. “I cannot be an outsider to the revolutionary movement to judge its rights and wrongs, democratic and undemocratic acts, good and bad, and successes and failures. I am not only influenced by their politics but also by their personalities,” he would say humbly.

Part 5

Leaders who structure organisations often tend to stay away from its on-ground activities. They are not as acquainted with practical realities as they are with negotiating and making decisions at the highest of levels. VV has always detested such an approach. He would consciously make efforts to blur the lines between mental and physical labour, ideas and praxis, and poetry and activism. While being regarded as a poet and editor, VV would easily blend in as a commoner. He wrote Ooregimpu, after participating in the rally of the first Virasam Conference in October 1970. The poem deeply reflects his ability of being a poet and also a participant in the rally, all at the same time.

Also Read: The Making of Varavara Rao: Part One

Let me now take you all through the early days when I closely witnessed his organising.

It was 24 August, 1973. A protest was organised against rising prices, and the students’, employees’ and workers’ unions of Warangal were to march from Veyi Sthambala Gudi to the Collectorate, against the reticence of the government in this context. I had moved to Hanumakonda for an admission into the 8th standard and went along with VV to the protest march. After the procession moved two furlongs further and reached Raganna Darwaaja, some Congress Party activists entered the march with flags. VV confronted them aggressively and impeded them from participating in the protest as it was the same party that was responsible for the hike in prices. The situation escalated quickly. Students in the march pulled down and burnt the Congress flags and drove the leaders away. This offended them and they teamed up with the police to corner the march. As it reached the Arts College and the IG Office from where the protestors could not escape, they attacked the procession and rained blows on them with lathis. VV was beaten black and blue. Another Virasam leader, Atluri Ranga Rao, and two student leaders, Bhujanga Rao and Raveendar, were badly injured as well. The police abducted the student leaders and took them to a station. From the place of the incident, the Collector’s Office, the destination of the rally, was only a few meters away. Kaki Madhava Rao was the District Collector at the time.

Despite the brutal attack, the protesters reached the Collector’s Office. VV and Ranga Rao who were leading the protest, were covered in blood. The whereabouts of the severely injured and abducted students were unknown at the time. The mob grew stronger and so did their protest. VV stood on the stairs of the government building and addressed the crowd. After a while, the Collector came out of his office, stood by the side of VV and expressed his regret for what the police did and assured that the captives would be released immediately. The protest was not called off until the two student leaders were released. That was when I witnessed VV’s resolute, aggressive and fearless activism for the first time.

Three months later in October, the Virasam Literary School was conducted at Warangal. VV had made his mark as a poet, an orator, teacher and Editor of Srjana. In the politically charged atmosphere of the time, there were college students who were willing to do anything he would ask, but he got involved in each and every task. The college that was rented to conduct the workshop was suddenly unavailable a day before the programme, and so was another hall which was promised. In such a situation, a 33-year old, lean and determined VV ensured that the three-day literary school, the open-air meeting, a 7-8 kilometres long rally and as well as a public meeting at the end of it, all took place as scheduled. Such was VV’s revolutionary verve. The word was his weapon. I have seen his organisational fervour and intellectual capability, as an activist and as a poet, his vision and his impeccable execution of it, the irresolute discipline and his courage until 2018. Thousands of people, along with me, have witnessed the same.

It is in this vein that he tried to blur the lines in organisational activity. He strived to do away with divisions such as age, caste, religion, wisdom, work-load, mental-physical labour, intellectual-practical work and the like. This was at the centre of his writing, editing and giving literary and ideological guidance to revolutionary groups and publishing houses.