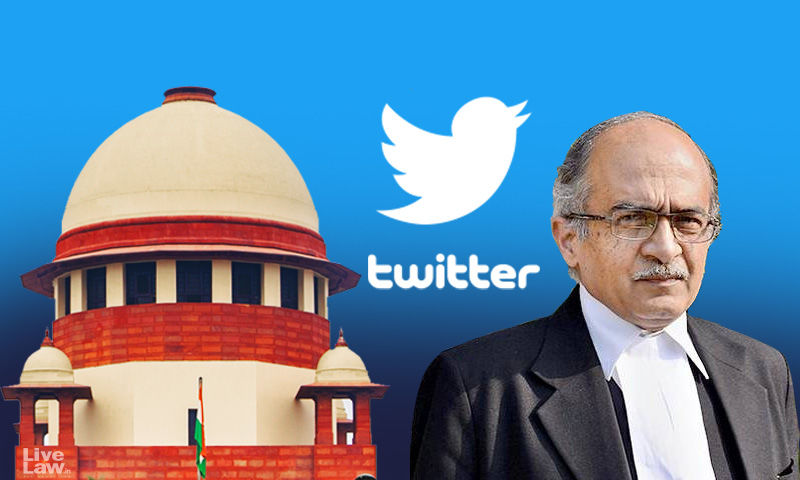

A Supreme Court bench comprising Justices Arun Mishra, B R Gavai and Krishna Murari on Friday August 14 held Advocate Prashant Bhushan guilty of contempt of court. The judgement came in a suo moto action initiated by the court for two of his tweets about the Chief Justice of India and the Supreme Court.

The apex court of our country is considered as the protector of the fundamental rights of every person which includes the right to freedom of speech and expression. Contempt, according to the Indian Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, may be civil or criminal. Civil contempt is wilfully disobeying an order or an undertaking given to a court. Criminal contempt could flow from an action or publication that scandalises or lowers the authority of any court, obstructs the administration of justice or interferes with the course of judicial proceedings.

Days after the verdict, statements have been issued by lawyers, activists, members of civil society criticising the judgement for constricting freedom of speech and expression. Many legal scholars, senior advocates and former judges have expressed serious reservations over the judgement and the manner in which the case was heard.

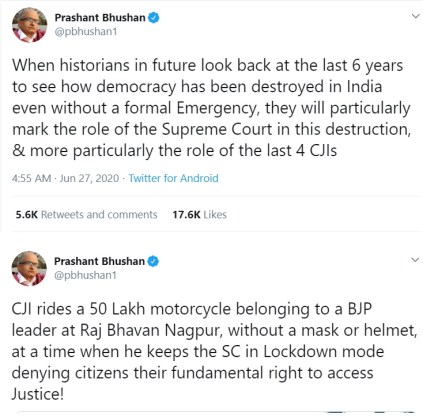

The judgement drew widespread criticism across the country, and it is said to have a “chilling effect on people expressing critical views on the functioning of the judiciary.” In the two tweets in question, Prashant Bhushan criticised the Supreme court and the Chief Justice of India. While one of the tweets spoke of destruction of democracy in India and the Supreme Court’s role in it, the second tweet remarked on photos of Chief Justice SA Bobde posing with a Harley Davidson in Nagpur while the courts are functioning in a lockdown mode.

The bench held Bhushan guilty of making “scurrilous allegations”, that are “malicious in nature” and “have the tendency to scandalize the court.” According to the court, the two tweets cannot be said to be a fair criticism of the judiciary and held that the tweets undermine “the dignity and authority of the institution of the Supreme Court of India and the CJI.”

Statements against the Judgement

Lawyers, legal policy experts and academicians have written a letter to the Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA) to register their protest against the judgement. The letter points out certain procedural flaws in the manner the case proceeded. The case was listed without the Attorney General’s (AG) consent that the law mandates. The court bypassed this requirement by converting the case in suo moto action. Even though a notice was issued to the AG, his oral views were not sought by the court. Moreover, an eleven year old contempt case against Bhushan was brought out hurriedly and listed by the court for a hearing.

The letters questioned the “cherry picking of cases during a pandemic during COVID-19”. It urged SCBA President, Advocate Dushyant Dave, to take up the issue and ensure a proper hearing and requests public access through the sharing of the link of the hearing in interest of open court hearings.

More than 3,000 members of civil society including former judges, retired bureaucrats, journalists and lawyers, criticised the judgement. The signatories said that expressing concern about the functioning of the judiciary was the fundamental right of every citizen. Additionally, over 2,300 members of the Bar have issued a statement condemning the Supreme Court’s decision. The statement said a “silenced bar cannot lead to a strong court”. It adds “An independent judiciary does not mean that judges are immune from scrutiny and comment. It is the duty of lawyers to freely bring any shortcomings to the notice of bar, bench and the public at large.” The statement also requested the court to not give effect to the judgement before a larger bench to review the standards of criminal contempt.

The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) in its statement said that the Supreme Court verdict slamming Prashant Bhushan’s critical tweets of it is “a sign of the current deterioration in the state of free speech in the country.”

People’s Union of Civil Liberties have issued a statement expressing dismay and disappointment over the verdict. It states “PUCL feels that the finding of the SC is not only unfortunate but will also have the contrary effect of lending substance to the view that just like how other democratic institutions in India are criminalising dissenters, the SC too is unwilling to acknowledge serious issues about the way the judicial system is functioning,”

Bar Human Rights Committee of England (BHRC) and Wales too issued a statement expressing concern over the verdict and stated that it amounts to an interference with “legitimate criticism”.

BHRC states “Scandalising the court, judiciary or judges is an old English common law offence, consisting of the publication of statements attacking the judiciary itself and likely to impair the administration of justice, as opposed to obstructing court proceedings or the administration of justice.” It further added, “In England the offence had not been prosecuted for over 80 years and as such, the Law Commission recommended its abolition in 2012, which subsequently took place through the Crime and Courts Act 2013. The Law Commission concluded the offence is in principle an infringement of freedom of expression that should not be retained without strong principled or practical justification, is no longer in keeping with current social attitudes, and is unlikely to influence the behaviour of publishers.”

Members of the bar association at Chennai have written a detailed letter to the Chief Justice of India expressing their anguish and have argued that “court has not exercised caution, wisdom and circumspection, as is mandated by the law, in ascertaining criminal contempt.” They state, “The opinions expressed by a fearless Bar actually benefits the judiciary, as it has no mechanism to learn about the people’s opinion of its functioning. The judiciary does not function in a vacuum but in a political system impacting the lives of millions. The letter adds, “No system can thrive without naysayers, for often progressive reforms have emerged out of dissent.”

Individual Voices against the Judgement

Former Supreme Court judge, Justice Kurian Joseph, has suggested that there should be a provision for intra-court appeal in verdicts passed by the top court in suo moto contempt cases. According to him the contempt verdict in the suo moto case against Justice C S Karnan was passed by a bench of 7 senior judges. Thus for him, “Important cases like these need to be heard elaborately in a physical hearing where only there is scope for a broader discussion and wider participation“.

Opposition leaders, human rights organisations and lawyers criticised the Supreme Court’s verdict on criminal contempt and called the judgement “alarming”, and a “dark day for the Indian democracy”.

Communist Party of India (Marxist) General Secretary Sitaram Yechury said that the judgement, “brings into the ambit of contempt, bona-fide criticism of the role played by Supreme Court as a constitutional authority, and it would prevent open and free discussion on the role of the Supreme Court in the country’s democracy.” Moreover, Lok Sabha MP from the Trinamool Congress, Mahua Moitra, said on Twitter: “To the First Court of our land – remember YOU are the standard for millions of poor who even today say ‘I will go to Court’ – brute display of power does not become you. It shames us all.”

Senior Advocate and former Additional Solicitor-General of India Indira Jaising as a keynote speaker in a press conference hosted by Indian-Americans appealed to the Supreme Court to reconsider the judgement on contempt of court over two tweets. She sought for a full Court of 32 judges to hear the matter. She noted that the Supreme Court’s “core function of dispensation of justice belonged to everyone and they had to be accountable to the public at large. This accountability could only be exercised with free speech, without fear of contempt.” She asks in her speech, if the offence of criminal contempt should survive in our contemporary society at all and as citizens have a duty to be vibrant in their respective criticisms, the judgement has shaken the very foundations of free speech.

Jaising: We represent the marginalised. An Indian citizen’s public jurisdiction is public. This gives us the locus to dissent. How can we be stopped ? We must realise that Courts are our allies. We are bound by “undeserved want”; a term in our Constitution of India.

— Live Law (@LiveLawIndia) August 19, 2020

In her article on BloombergQuint, she points out an important flaw in the judgement that the case proceeded without obtaining the consent of the Attorney General as required under the Contempt of courts Act. While the court derives its power to punish for contempt through Article 129, the procedure to activate that power has been laid down through the act and needs to be followed. She states, “By far the most dangerous implications of the judgment is this assumed power—to open the doors to the court at will, and punish for contempt. Is this even constitutional…being held guilty of a crime without a charge being framed, or the red herring on malintention to scandalise the court? This alone makes the judgment erroneous in law, anti-constitutional, and a great setback for the rights to life and free speech.”

Pritam Baruah, an academic, wrote in article14 that in convicting Prashant Bhushan of contempt, the Supreme Court partly relies on a 265-year-old British case, from an era of undue deference to authority. It used “dignity” 31 times and “authority” 50 times in a vague, murky formulation that is the province of sophistry rather than legal justification.

Political economist Prabhat Patnaik wrote, “Contempt laws are a hangover from the days of colonial rule and are incompatible with a democratic polity. This is the reason why in most countries where democracy is sought to be strengthened, contempt laws have been done away with.” He added, “What is sad is that in India, far from such laws being removed, they are being used to stifle criticism of judges that have not been shown to be untrue or unjustified.”

Many senior lawyers across the country have written extensively on the judgement and criticised it on various grounds. Senior advocate Sanjay Hegde remarked that the Supreme Court’s order would discourage lawyers from speaking freely, The HuffPost reported. “A silenced bar cannot lead to a strong court,” he added. “Prashant Bhushan joins the ranks of EMS Namboodiripad and Arundhati Roy in having been convicted by the Supreme Court on a charge of contempt. The judgment will add to textbooks on contempt, but will leave most readers wondering whether it does anything to restore the authority of the court in the eyes of the public.”

Senior Advocate Iqbal Chagla in his fierce criticism wrote in Indian Express that Supreme Court’s judgement in Prashant Bhushan case spells out a chilling lesson that undermines the most valuable fundamental right — the freedom of speech.

Arvind Datar, a senior advocate, raises two important points of criticism against the judgement. First he argues the conversion of a petition filed for contempt into a suo moto action and, thus, bypassing the requirement of the consent of the Attorney General, not permitted in law and is erroneous. He further argues that the judgement does not engage with the arguments made by Prashant Bhushan in his affidavit- “It is submitted that failing to consider the response of Bhushan is a serious error and requires the recall and reconsideration of the judgment. The contempt jurisdiction should never be used to bludgeon criticism.”

Legal scholar Gautam Bhatia makes similar criticism in his blog. He states that there was no legal reasoning in the judgement, and therefore nothing to analyse. He added Mr. Bhushan had filed an extensive reply to the contempt proceedings against him, contextualising and defending the two tweets for which these proceedings were initiated; among other things. The Supreme Court, however, refused entirely to engage with Mr. Bhushan’s reply.

He adds, “There are some colourful – and somewhat confusing – references to the Supreme Court being the “epitome” (?) of the judiciary, the need to maintain “the comity of nations” (?!), and an “iron hand” (!). There is, however, no legal reasoning, and no examination of the Reply.”

In an interview to Karan Thapar for The Wire, Arun Shourie makes strong criticism of the Supreme Court’s record in past few years and particularly with respect to the verdict on Prashant Bhushan’s contempt case. He asks, how can a puff of two tweets shake the central pillar of the largest democracy in the world.

Review application by Prashant Bhushan

Lastly, a day prior to the sentencing hearing (scheduled for today), Bhushan filed an application before the Supreme Court seeking deferment of the hearing on his sentencing and has requested the Court to postpone the hearing on sentencing, till he files a review petition and until the same is decided upon. He alternately prays if the hearing on sentencing is not deferred then the sentence may be stayed till the time the review petition is not decided.

He notes “In criminal contempt proceedings, this Hon’ble Court functions like a trial court and is also the last court. Section 19(1) gives a statutory right of appeal to a person found guilty of contempt by the High Court. The fact that there is no appeal against an order of this Hon’ble Court makes it doubly necessary that it takes the utmost precaution to ensure that justice is not only done but seen to be done.”