I remember standing in a lot of queues. But bookshop queues was the first instance where I started to appreciate the art of selling books. It has been a long journey of finding the whole process unimaginative and pointless, to finally grasping what it is, which made it a sticky memory later on.

My parents ask a lot of questions, but I was never asked which school I’d like to go to. I was not expecting it from them either. The need to wrap notebooks with brown paper was always more important than knowing if a library would be available for a child in class I.

Books were the top priority in the month of March when money was allocated for various goods and services. Dinner time conversations would change to how we do not need name slips, do not need to buy new books for my brother, and that my brother needs to stop sulking at the remark of using my books.

My first encounter with a bookshop was at school. It was also known as a “stationery shop”. The world outside the bookshop seemed mechanical and boring. I could sleep waiting in those lines and sometimes I think I actually did!

As the frequency of my visits to bookshops increased, it became a matter which required planning, discussions, and time management. We developed strategies on how best to get to bookshops, to thwart crowds, collect the books in a jute bag, which was also used to buy vegetables, and more. My father would always have the best solution: “We will wake up early and reach the school early.”

Once we reached the bookshop, it was all about noticing the eyes and hands. It began with the eyebrows or a gesture game. The bookshop uncle with an oval face and short white hair sprouting from the sides of his ear, would raise his eyebrows and I would have to tell him which class I had been promoted to. No questions asked. All answers given! When the shop was too crowded, all he would say was “haan?” — which meant a million questions, including what do you want; will it be notebooks; or maps and atlases; or is it going to be books that are not available for which you would have to come again.

At such bookshops, I saw what multi-tasking, parallel thinking, alternate attention, and even care were. With one hand, uncle would give us those books and with another, he would take the name-slips away.

Surely, there is labour when we deal with books. A set of muscles gets pulled into creating a memory for people like us who would come home to a new collection of NCERT books, Three Men in a Boat, Ali Baba and Chaalis Chor, a new Atlas and the smell of the freshly printed copies.

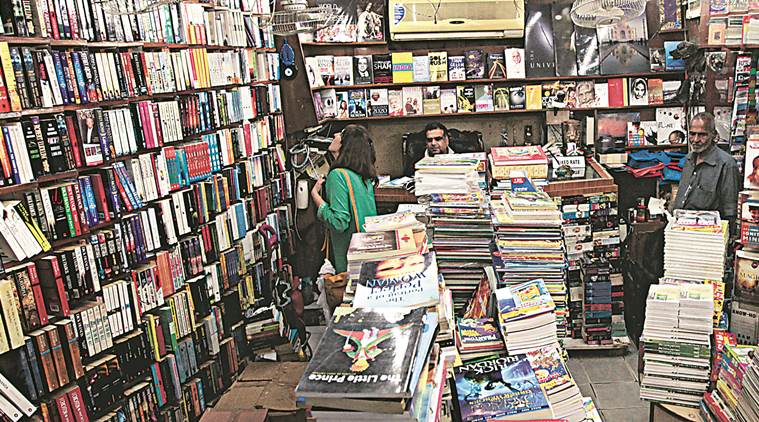

As much as a bookshop is about the books in it, what we tend to forget is the bookshop itself. What is a bookshop? Simply put, it is a shop where books are sold.

In his essay ‘On Visiting Bookshops’, American journalist Christopher Morley impressively explains how he loves to be in connection with books and how these books have catered him new experiences of discovering and finding further meaningful readings.

But the b-o-o-k-s-h-o-p remains an easily forgettable space.

In Alice Munro’s short story, ‘Dulse’,, the lead character Lydia is a lone woman. “For she has been divorced for nine years — but also self-consciously alone. Something about her identity has profoundly shifted, and she sees herself differently now”. In one of the passages, Lydia is thinking about her relationship with Duncan, whom she first met in a bookshop, asking for a copy of The Persian Letters. Munro writes, “He revealed a need that she (Lydia) supposed was common to customers in bookstores, a need to distinguish himself, appear knowledgeable.”

In another one of Munro’s short-stories, ‘Hard-Luck Stories’, three characters — nameless female narrator, Julie, and Douglas — are revealed to have a preoccupation with thinking about the past. These characters move back and forth in time, thinking back on themselves thinking back, sharing those ‘hard-luck stories.’

Douglas, a character in the story, mentions a certain kind of roguish confidence associated with people who deal with books. He goes on to say, “In this, as in any other enterprise where there is the promise of money, intrigues and lies and hoodwinking and bullying around.” “People have this idea about anything to do with books,” contributes Julie. “They have it about librarians. Think of the times you hear people say that somebody is not a typical librarian…”

Our bookshop uncle hardly held any peculiarities noticeable to us. He’d finish eating lunch either in the fifth or the fourth, or the seventh period. He’d also have long discussions with the canteen caretaker on any day and early morning hustling guardians on Parents’ Visiting Days would be greeted by his non-creased forehead. When the queuing would begin, his spectacles would be back on.

At the bookshop queues, the unfortunate victim was the disappearing bookshop and other minute details, like the wooden panel, the light bulb inside, the file covers kept on side. The gestures were about the transaction, profit and loss, people saying they did not need notebooks, about thumping on the wooden deck to get attention, and more.

The character of these queues comes alive for me in my memories and descriptions, because both order past experience and re-collect lived moments within a chronological frame — thereby conserving a certain kind of loss. When I look back on what I remembered, the whole narrative of being in queues is also a predicament of being at a loss — loss of queue means loss of crowd, means loss to bookshop, means loss of approximating experience.

Sometimes in these queues, parents trusted other parents. They handed over the money to whoever was closest to the bookshop and asked them to buy. Once we purchased books for ourselves and notebooks for another person whom I never saw again. At these sites, friendships were a discomfort as it was competitive. Fights would break out at the touch of a book. Too many things were being bought together.

Over the years, I started associating bookshops with crowds at all points of time. I remember asking my teacher to let me go five minutes before the bell would go for Break, so as not to get stuck in the crowd at the bookshop. But as soon as I got there, a group would already be surfacing. I had to give money to taller, stronger, people who drank Horlicks, to buy my stationery. And in between this, some change would always get lost. Next time, I had to ask my teacher to leave me seven minutes early. Over the years, I became more careful and bought the stationary that I needed beforehand from a general store near my house.

Few months later, the bookshop also started selling school bags. A small part of the bookshop was extended, and school uniforms made space along with the textbooks. First, it was socks, belts, coats with school emblems. Later on, the entire uniform could be bought from the bookshop.

The take-over by the sale of uniforms was also the first sign of the incoming of digital books, availability of pdfs, and people finding other places to buy books rather than school stationery shops. Uncle started wearing white and cream shirt more often. Aunty became responsible for selling uniforms. They both were doing this together in the bookshop.

With all these changes, the queue did not take any offense. It swelled and elongated, changed directions, shifted from one place to another, but never once disappeared (probably because we see survival in numbers).

When books had been bought and buyers moved out of the queues, the view always looked like a molecule breaking and dispersing and entering the gaseous state.

As much as the function of queues at bookshop was to restrain the crowd, there was always a mordant understanding of an event unfolding at the space of a bookshop queue.

Sometimes the queue became simply like the people standing in it, attempting to understand their experience by going through it again, but only memory allows this review. To repeat is at best to revise, but never to perfectly relive it again.