An upcoming Malayalam film on the Malabar Rebellion has invited widespread attention and controversy following the release of its poster last month. Purportedly named “Variyamkunnan”, the film is on Variyamkunnath Kunjahamed Haji, one of the leaders of the Mappila uprising that took place in Kerala’s Malabar religion in 1921, who was shot dead by the British. Initially, the announcement of the film on social media led to a hate campaign against it from members and supporters of right-wing groups in Kerala. However, the makers of the film soon found themselves in another wrangle with one of its script writers being caught in a controversy of his own.

It all began on June 22, when director Aashiq Abu (42) along with actor Prithviraj Sukumaran (37), who is set to be play the lead in “Variyamkunnan”, uploaded the film’s poster on their respective Facebook walls with the following lines:

“He stood up against an empire that ruled a quarter of the world. Etched out his own country with an army that waged a never before war against the British. Though history was burned and buried, the legend lived on! The legend of a leader, a soldier, a patriot. A film on the man who became the face of the 1921 Malabar revolution. Filming begins in 2021. On the 100th anniversary”.

Following this, the right-wing in Kerala, particularly the Hindu Aikya Vedi, began a vicious campaign against the two of them, accusing that there was a “hidden agenda” behind the film. On June 23, OpIndia referred to Variyamkunnath as a “jihadi” and a “terrorist” and accused him of murdering “thousands” of Hindus during the rebellion.

RV Babu of the Hindu Aikya Vedi said to the media, “We have asked Prithviraj to step down from the film because we feel he is loved by people across caste and religion, so he should not fall prey for this distortion of history. Victims of the Mappila Rebellion still live in areas of Malabar”.

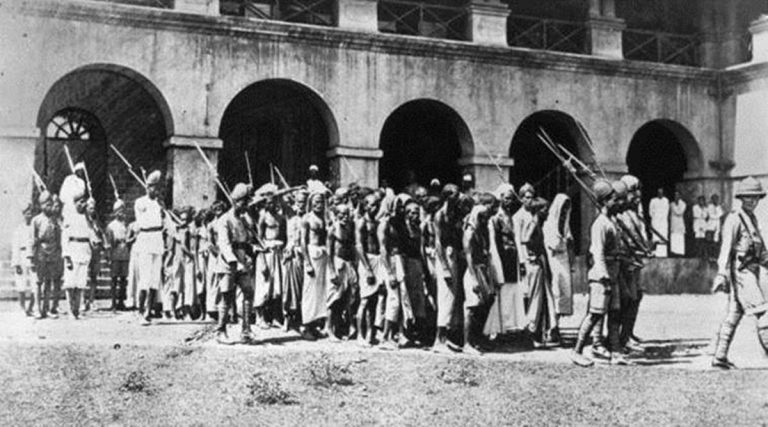

The Malabar Rebellion, also known as the “Mappila Rebellion”, owing to the community in northern Kerala that led it, has been the subject of multiple studies and academic research both within Kerala and outside since many years now. Historians KN Panikkar, KKN Kurup, Stephen Dale and Conrad Wood happen to be some whose works are oft quoted. The controversy re-opened up older arguments about the issue in Kerala which had remained forgotten since then.

The most primary site of contention regarding the Mappila Rebellion is the “why” or the nature of it — whether it was purely religious or material. KN Panikkar is one of the earliest historians from Kerala to have produced considerable academic work on the Rebellion. In his book, titled Against Lord and State: Religion and Peasant Uprisings in Malabar, 1836-1921, Panikkar takes a multidimensional approach towards the issue and argues for the complex character of the uprisings. He argues that the reasons behind them were both material and ideological in nature, and that although religion “enabled” them, the rural poor Mappila participants were driven by their opposition towards their landlords, who happened to be Hindus, and the colonial state.

Historian Manu Pillai, in a recent interview to The News Minute said, “The rebellion certainly had a religious angle as well as a sustained economic angle, and a political aspect both local and linked to the wider Muslim world”. He added, “Bearing in mind that much of the peasantry was Muslim in South Malabar, where Mappilas were concentrated, and nearly all landlords were Hindus, you can trace the economic logic to the clashes, as well as how this quickly became communalised”.

While Pillai agrees that there must have been murders of Hindu landlords during the Rebellion, he denies that the reasons for this were purely religious or communal, contrary to what the perpetrators of the recent hate campaign have claimed. Mappilas, who used to enjoy considerable power, position and honour from local Hindu rulers, were brushed aside with the arrival of European trading companies, with whom the rulers then got into doing business. This, Pillai argues, was the context for the many uprisings that took place in that period and culminated in the 1921 Rebellion. As far as conversions were concerned, Pillai reminds us in the interview of the caste angle of the issue — the second half of the nineteenth century was when many “lower” caste Hindus of Malabar converted to Islam and became Mappilas. This gave them a voice to stand up to the rulers. Many of them were, consequently, active participants in the uprisings against the landlords.

“To Mappilas, the British and the jenmis (upper caste Hindu landlords) sat on the same side of the coin in an oppressive alliance. This is why anti-colonial and anti-Hindu feeling may have coalesced as one substance, giving ideological force in religious wording,” opines Pillai.

Amid all of this, The Hindu on June 26 republished an old letter written to them by Haji himself, regarding reports on “forcible conversions” and “large scale killings of Hindus” as part of the Rebellion. In the letter, dated October 7, 1921, Haji argues that it was “entirely untrue” to say that such incidents happened.

The Government of Kerala, meanwhile, has declared the Mappila Rebellion a “fight against the British” and the participants, “freedom fighters”. The issue was soon taken up and discussed at length by regional news channels in Kerala for the rest of the week. Members of the state’s civil society and political leaders too joined in. “I’m not aware of the controversy, but Variyamkunnath Kunjahammed Haji is one of Kerala’s brave men who fought the British and has always been respected by all of us in the state,” said Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan when asked by a mediaperson during a press conference on June 23.

CPI(M) Kerala State Secretary Kodiyeri Balakrishnan wrote on June 26, “The RSS is trying to infiltrate each and every aspect of Indian society to establish that what they proclaim is history and that what we live in is a Hindu Rashtra. It’s in this context that they’ve come out against a film based on the life of Variyamkunnath Kunjahammed Haji, a brave soldier of the Malabar Rebellion”.

“The nature of the temporary ‘Malayala Rajyam’ state established by Haji and his companions as part of the Rebellion, which functioned for around 4-5 months, was what attracted me towards the subject. As I understand, the state had abolished the caste system. Besides, it generally espoused a progressive vision towards agricultural labour and wages; Haji addressed communal strife between Hindus and Muslims and acted against it. All in all, it seems to have been a secular, socialist state. This was the source of my excitement,” said Abu in an interview.

However, by the end of the week, newer issues began showing up regarding those behind the film, particularly one of its two script writers. Social media, especially Facebook, surfaced with his write ups from some years ago that contained offensive remarks about women and politically extremist statements. These were raked up by people from progressive circles who questioned the integrity of the makers of the film. Abu, who used to be a student activist during his time at the university, is known as a left-supporter in the state and has openly taken stands in support of the CPI(M). This issue too grew into large proportions and Rameez stepped down temporarily from the film.

Subsequently, on June 27, Abu wrote on Facebook, “I have differences with Rameez’s political views. He would probably disagree with mine too. For some years now, discussions about this film have been going on with another director as well. I came to know of Rameez only around three-four months back. Following the allegations, an explanation was sought and he had publicly apologised on social media”.

As Panikkar wrote in 2009, culture and historiography continue to remain sites of struggle between contending ideologies that seek to establish their hegemony over them. This, he says in Culture as a Site of Struggle, is because the writing of history has always been tied up with the realisation of social and political power in all societies. Communalising history has two main aims: one, to “identify religion with culture” and two, to “redefine the nation exclusively through this relationship”.

While the fate of this film is still unknown, Kerala is gearing up to receive three other takes on the same issue. The evening Abu and Sukumaran announced their venture on social media, filmmakers Ibrahim Vengara and PT Kunju Muhammed, came up with their similar plans. Soon, local BJP activist and director Ali Akbar followed suit, saying that he would also be doing a film on Haji to “reveal his real face”. Despite a century having passed, the Mappila Rebellion will remain, it appears for many years to come, a site of struggle for varied interpretations.