June in Kerala began with the devastating news of a 14-year old’s suicide in Malappuram, which allegedly took place due to her lack of resources to attend the virtual classes organised by the state government. To circumvent Kerala’s strict COVID-19 restrictions put in place since two months, the government’s Education Ministry has begun online classes for public school students — the pilot series of which was released on the first of this month.

“There is a television at home but that has not been working. She told me it needed to be repaired but I couldn’t get it done. I couldn’t afford a smartphone either,” said the 14-year old’s father to the media. The family belongs to a Scheduled Caste background and the father is a daily wage earner.

The Chief Minister in a press conference later in the day repeated what the government had stated earlier — that the initial set of lessons were trial classes that were to be retelecast entirely the week after. Unlike in other places, Kerala has gone a step further in democratising the process by televising the classes through a government-run channel available on all cable TV networks, ensuring that they are not on the internet alone.

Named “First Bell”, Kerala’s virtual school education programme for the academic year 2020-21 is jointly executed by the Kerala Infrastructure and Technology for Education (KITE), the State Council of Educational Research and Training (SCERT), Samagra Shiksha Kerala (SSK), and the State Institute of Educational Technology (SIET) — agencies owned by the state Education Ministry. The classes are telecast on KITE-run Victers channel, as per a daily timetable that has been publicised across the state. They are also uploaded on YouTube and on its own website. The sessions are held on weekdays for classes I to XII. In a downloadable format, classes can be stored and viewed later as well. The classes are also available at Akshaya Centres, which are state government-run resource hubs that carry out a wide number of activities and work in between the State and the public in various localities.

Prior to running trial lessons, the SSK carried out an extensive survey to calculate the number of government/aided school students who didn’t own an internet connection or a TV, and the estimate was over 2,61,754 lakh families with either of these. This is nearly 6% of the total. According to the Broadcast India Survey 2018, TV penetration in Kerala is 93%. It was later understood that the 14-year-old who had to succumb to suicide was part of the said SSK list.

From around March, teachers were rigorously trained to carry out the experiment, following which around 82,000 teachers passed.

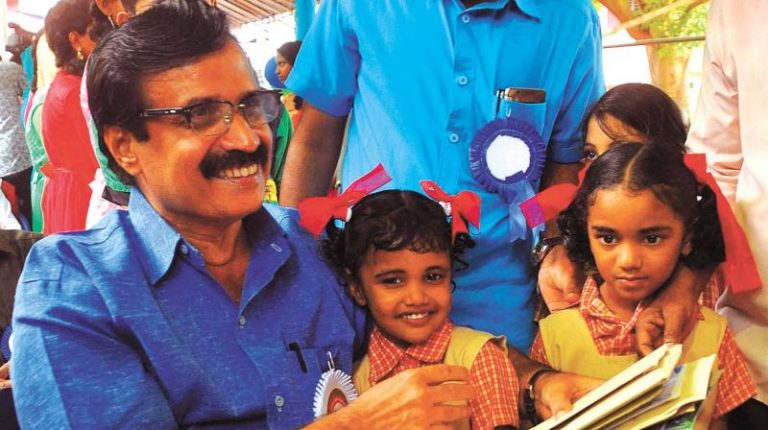

“June 1 marks the beginning of the next academic year and we know that the pandemic has made it impossible for both students and teachers to travel to schools. The government, therefore, has sought a myriad different ways to overcome this situation. Conducting virtual classes happens to be the most important among these”, said Kerala’s Education Minister C. Raveendranath on May 30.

He added, “The first week is a trial period. We’d like people to report to us the shortcomings and possibilities of this mode during the first seven days, including how many will not be able to access this facility. We need people’s complete participation and support for this endeavour”.

The suicide shook Kerala to no end. Subsequently, progressive organisations that had already decided to distribute television sets and other devices across the state to aid virtual education, stepped up their game. Activists from youth and students’ organisations like the Democratic Youth Federation of India (DYFI), the Students’ Federation of India (SFI), groups of techies based in Kerala and the like began carrying it out vigorously. Very soon, this was taken up by governmental and non-governmental agencies, local MLAs and MPs beyond party lines. Civil society joined in — common study rooms were soon set up in the remotest of localities. Libraries were converted for students with no electronic devices of their own to gather and attend the virtual lessons.

“What is unique about the progress that Kerala has made in education is widespread public support. Students from marginalised regions and social groups should not fall behind in academics. All of us must collectively ensure that this is done here. The public, with the help of panchayat officials, must figure out the number of families that do not even own TVs and set up local study rooms”, said Financial Minister and economist TM Thomas Isaac to the media.

Following this, the government announced their offer to financially support the distribution of television sets and laptops. The Kerala State Financial Enterprises (KSFE), a public sector chit-fund and loan company, and local self governments were given the responsibility to take care of the matter in each locality. According to Isaac, the KSFE will contribute around 75% to local self government funds in order to procure the devices required, especially television sets. Besides, MLAs were asked by the State to spend their local development funds on buying TVs and laptops. Kudumbashree has also been equipped to help out. Additionally, schools have been provided with laptops, projectors and TVs that can be used by those in need.

On June 4, Kerala’s Industries Department launched a “TV Challenge“, inviting the public to contribute new television sets to be later distributed to students who could not own one. “Right now there are many children who are incapable of attending the government’s virtual lessons. This challenge is to provide around 2000 new TVs to the Education Department,” wrote EP Jayarajan, Minister for Industries. Within days, many local businessmen joined in to contribute TV sets to their nearest District Industries Centre. Kochi MP Hibi Eden of the Congress kicked off a “Tablet Challenge” in his constituency.

Interestingly, all of this is happening when parts of the rest of the country have seen protests led by students against the exclusive nature of online education and examinations. Progressive students’ and teachers’ organisations based in New Delhi spoke out and protested against Delhi University’s decision to shift examinations online, citing the dangers of a “digital divide”. On May 20, students’ unions and organisations from across the nation led an online protest to “save public education” and against the central government’s move to shift it online, at a time when a majority does not have access to the internet. What makes Kerala’s experiment different is that while there is a shift to the virtual, conscious efforts are simultaneously being taken to make this shift accessible to all through a decentralised process. Class teachers and school headteachers are entrusted with the responsibility to report the number of students who do not have access to electronic devices. The government has also decided against conducting exams online since that requires further preparation.

Progressive measures in the realm of the digital and virtual in Kerala have been taking place increasingly lately. “Kerala has walked ahead of India in fostering a visionary zeal with regard to the democratising potential of the digital. In 2019, the State declared the internet as a basic human right, in an act of prescience that far surpassed the technological aspirations of the rest of the nation”, Meena T Pillai told the Indian Cultural Forum. Pillai is a Professor at the University of Kerala and someone who has intensely studied the subject.

She added, “Probably a socialist understanding that the underprivileged and dispossessed have as much right to the digital as anyone else, and that lives and livelihoods needed to be revisioned within the concept of a digital democracy, spurred the state to aspire for new milestones”.

Wayanad, one of Kerala’s northern-most districts, was found to have the most number of families with no TVs or other devices. The estimate is 21,653 here, which is 15% of the total number of students in the district. Around 9,200 common study centres were set up here with the help of the local MLA of Kalpetta, CK Saseendran and others. The district is also understood to contain the maximum number of tribal families in the entire state. Power connections and availability of TV sets were ensured in these homes as well, as per Saseendran. Many such common study rooms have been opened in several parts of the state even without government aid. Similar work has been taken up in coastal areas by the Matsyafed or the government-run cooperative federation for fisheries development. It started off with the count of families without adequate facilities across the coast being submitted to KSFE, according to Isaac.

Pillai said, “From the long cherished dream of 100% literacy that made Kerala so unique, to new aspirations for internet in every household and free internet for two million poor households, led to the setting up of the Kerala Fibre Optic Network, a joint venture of the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) and the Kerala State IT Infrastructure Limited. This, together with Kerala’s sustained attempts at decentralisation with focus on local planning, can hopefully help its public education bridge the digital divide while flattening social hierarchies”.

Today, around 43-45 lakh students tune in to KITE Victers for their daily lessons across Kerala. Virtual/remote education is not an alternative to the classroom, precisely since the former will not be able to offer the wholesome atmosphere the latter does. The aforementioned efforts are yet to reach multiple students in the state and it will take time. Progressive students’ organisations have stated that the primary aim of governments must be to set up more schools, classrooms and better educational infrastructure in general, keeping in mind the deeply rooted digital divide in the country.

The Indian Cultural Forum spoke to Amruth G Kumar, Professor of Education at the Central University of Kerala, who said, “The assumption that the digital divide can be bridged with digital tools is a naive one. Quality of the tools, availability of electricity, the internet, technical knowledge of parents, capability to sustain connectivity are also part of it. Digital divide is a complex and compound mix of economic, social, cultural and regional divisions”.

On the day of the school student’s suicide in Malappuram, CM Pinarayi Vijayan reinstated to the media that the shift towards online was “temporary” and that the government hoped to reopen schools at the earliest.

Besides issues of accessibility, the mode has also produced some other socio-political problems characteristic to the digital space. A day after the trial classes were telecast multiple cases of cyber harassment began surfacing against some of the female teachers. Screenshots of the women were circulated via newly formed “fan pages”. The Social Justice Department has taken a suo moto case.

“From the very beginning, we have been clear about the fact that this is not an alternative to school. This is to help students fill that gap before entering the academic year,” said K Anvar Sadath, CEO of KITE to The Indian Express.

However, at a time when academics is entirely at a halt for a majority of school students in various parts of the country, with the central government pushing for a pipedream without ensuring adequate infrastructure, Kerala definitely stands out. The state is now witnessing a historic mass movement that could give us crucial lessons on both how to save public education and democratise virtual learning.