Epidemics have altered the course of history in more ways than one since they have given rise to certain socio-political and cultural developments. They produce specific vulnerabilities and issues in every society. They have had a significant effect on personal relationships, art, literature, and have reinforced inequalities and discrimination of various kinds across the world.

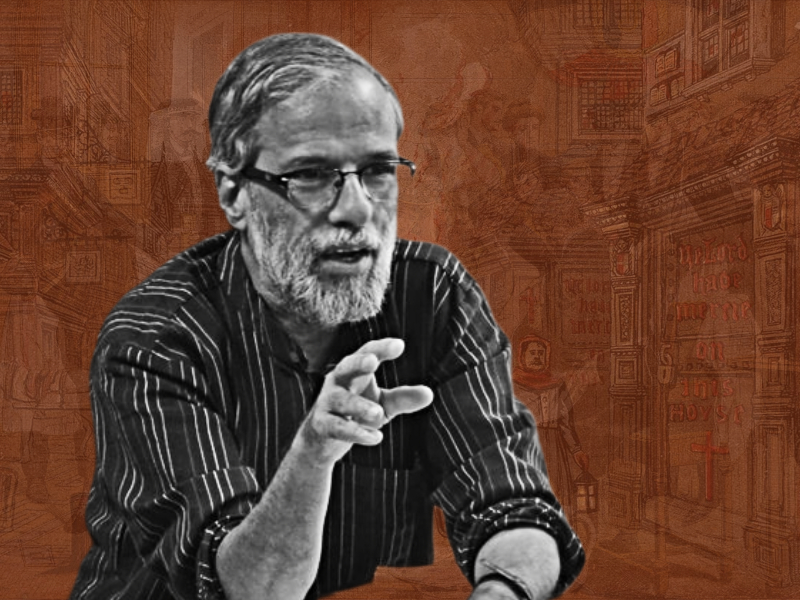

To make sense of all this, the Indian Cultural Forum has begun a mini-series with Indian historians. In the first, second and third features, Mukulika R spoke to Romila Thapar, Uma Chakravarti and Tanika Sarkar. In the fourth, we speak to Rajan Gurukkal who explores the condition of democracies during pandemics, Kerala’s response to the outbreak, whether pandemics are portals, and more.

Mukulika R (MR): The Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897 implemented multiple medical surveillance measures like plague passports, exemption certificates, and even detentions. The colonial Act was invoked by PM Modi last month, allowing for similar inspection and segregation to deal with the current pandemic. Do pandemics feed into the creation of super surveillance states or a “coronopticon” and how?

Rajan Gurukkal (RG): Aspirants of fascism use crises to make their power absolute. They intensify secrecy about themselves and excite fear among people. A life-threatening crisis serves both purposes with a single stroke. Further, any action upon people during a crisis goes justified under the pretext of social security. One cannot blame the government for using the Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897 of a comparable situation in the absence of another legislation suitable to manage the emergency condition. Nevertheless, citizens have to be vigilant about whether the provisions provided in the Act are invoked in good faith, to help contain the contagion or not.

Alleging privacy/data breach in today’s world of electronic sophistication is much ado about nothing. I know the fuss created over the Kerala government’s agreement with the American firm Sprinklr. If personal data were shared with pharmaceutical companies, they would have used it for developing drugs and finding markets for them. Companies need hard reliable data of tens of thousands of patients to do bio-pharmacological research. Is it not good for all the sick?

Where is privacy security if we have to pass through many CCTVs in everyday life, do pathological tests at times, and undergo biometric scanning occasionally? Governments need big data electronically gathered, quantified, classified and analysed for taking efficient administrative decisions for quick action. Let us recognise that we live in the age of state-controlled societies of individuals deprived of transactional anonymity, thanks to KYC-linked accountability.

MR: We have witnessed how scapegoating and certain prejudices get exacerbated in times of such crises on the one hand, and how power equations get reinforced on the other. Could you explain this situation?

RG: Democratic state powers of fascist orientation, heavily dependent on exciting communal or racial sentiments of the majority, will certainly use the emergency situation of a pandemic for their autocratic turn. They will try to boost racial or religious majority’s nationalities as distinct with precedence over that of the minority; nothing to speak about the immigrants. All of us have a fairly good understanding of it through history.

Fascists in democratic countries systematically instill among the dominant people a sense of insecurity by spreading the impression that religious or racial minorities are contesting for the nation and state power. This fascist game has surfaced across the world, reaffirming the majority’s national identities rigidly through othering the national minority and immigrants. In the wake of COVID-19, they have generated and sustained hatred against these misrepresented people as distributors of the contagion.

MR: Epidemics are considered by many to be capable of altering the course of history and opening new worlds, by stirring up demographic, economic, social, and cultural changes, often citing that the European Renaissance took birth in the devastation caused by the plague. Do you agree with the argument that the pandemic is a portal?

RG: Many facts, figures, quantitative projections and interpretations have come up assessing the gravity of the post COVID-19 downturn, mostly from the angle of growth, and hence obsessed with unknown threats to capital and compelling trade-offs. They all have anticipated economic and social consequences of the globally devastating health crisis, unprecedentedly severe. Will all this turn the world into another economy? Well, several critical political economists think that the COVID-19 induced downturn precludes recovery of the conventional capitalist economy. Some social theorists like Slavoj Zizek anticipate a post-capitalist phase of communities, not rigidly class-divided, enjoying equal status at various levels in terms of livelihood practices and relations of exchange close to communism.

Various world organisations have opined that merely repairing the damage caused to the global economy will not help anymore, and that it is inevitable to open up ecologically sustainable development paths leading to systemic change. However, such radical changes are not state-driven, for their course is always bottom up and people-driven. We should, therefore, look for indications in the survival struggle of the people during the crisis.

Manuel Castells and others have shown how ordinary people of the US, Europe and Australia had been experiencing the rise of alternatives during the financial crisis of 2008. Support not forthcoming from their elitist governments, they resorted to spontaneously evolving community practices of reciprocity and cooperation as survival strategies. Resorting to barter networks, ethical banking, digital entrepreneurship and cryptographic virtual currencies, they rendered another economy of new norms of exchange possible. Nonetheless, the market economy back to dominance could easily contain the alternative that the people are now reinventing during the COVID-19 crisis.

Post-pandemic recovery measures of governments caught up in transnational trade-offs will normally give top priority to doing everything to restore the global economy of capital flows. A series of new exactions like healthcare levy, salary cut, wage reduction, public expense cut and termination of welfare measures etc. would follow. Naturally, there would be people’s movements desperately demanding their governments to ensure better health security, redistribute wealth, enhance consumption, boost investments, and generate employment. Demands would certainly influence government policies a bit to provide for jobs, compensations, and better public healthcare. But there could be no measures to regulate capital growth in order to ensure distributive justice.

None of these can remain or scale up to bring about a systemic change for good, for an already mutated form of the dominant economy, techno-capitalism, is on the rise. Heavily dependent on commoditization of technology and science for turning knowledge into capital, it is a new type of capitalism, organised into corporates owning huge science-tech research establishments generating trillion dollars worth patentable knowledge and intellectual property called intangible assets. They account for as much as four-fifths of the total value of current products and services. This new version of capitalism is least worried about the COVID-19 induced recession.

Also Read: “I don’t see a brighter future beyond the pandemic”

Corporate research establishments the world over are exploring the micro universe of proteins and their dynamics through X-ray crystallography, high-field NMR spectroscopy, microarray technologies and automated methods. Their research is mostly in the latest science-tech hybrid areas like genomics, biopharmacology, biomedicine, synthetic bioengineering, bioinformatics, robotics, nanotechnology etc. Another field of accumulation for techno-capitalists is space technology, that combines high-energy plasma physics and shock wave hypersonic velocity technology, besides advanced refractory ceramics or ultra-high-temperature ceramic materials for aerospace applications. Thus latest science-tech knowledge production in both the micro and macro universes, techno-capitalist corporations have tens of billions dollars worth intellectual property in hand and many patents in the pipeline.

Unless the entire high-power computing knowledge workers are wiped out, the COVID-19 crisis will only boost techno-capitalist accumulation. So far the pandemic toll of science-tech human resource is too negligible. Definitely, there would be changes in the concepts of human relations, groups, institutions, and their roles. They would be behavioural changes of socio-cultural implication like robotisation of individuals. I do not foresee any fundamental, systemic transformation in the economy.

MR: Kerala today, especially it’s fight against COVID-19, is being celebrated across the world. Apart from its healthcare model, Kerala also seems to do better in terms of keeping the prejudices and inequalities of the aforementioned kind at bay. What are some of the historical and contemporary reasons for this?

RG: India, one of the world’s largest democracies though, is not an appropriate site to look for indications of an alternative economy in the wake of the pandemic? Panchayati Raj Nagar Palika self-governance initiatives (1992-93) helped the government to accelerate market development. It made little change in the local social power relations based on caste-class-community nexus that precluded democratisation. Nevertheless, this constitutionally ordained administrative reform made an exceptional difference in Kerala through People’s Plan Campaign (1996) under a Marxist government of democratic centralism. It did result in institutional development at the grassroots, especially people’s cooperatives providing the weaker section better access to local resources and power. People’s self-governing institutions with predictable share of plan funds for local level development enterprises distinguished Kerala from the rest of the states. It enabled the state to become nationally no. 1 in sustainable social development.

Kerala’s COVID 19-crisis management has drawn global attention due to its Chief Minister’s outstanding leadership, the health minister’s intimate involvement, and the functional competency of local bodies. What the developed world sees amazing is the unfailing thread of political control across local bodies of self-governance, multiple cooperatives, distributive networks, charitable societies, community service organisations and other agencies guaranteeing compassionate action on war-footing! It is coalescing different agencies of conflicting interests into a single task with absolute precedence of human values over economic gains. This distinct set up enables the state to effectively encounter the lockdown and its social consequences like livelihood loss, workers without income, farmers with unsold products, unemployment, abject poverty, starvation and more, without discriminating against minorities or immigrant workers, addressed by the state as “guest labourers”. It helps the state facilitate voluntary redistribution of wealth and circulation of essential goods to ensure social security. This is political structuring of the economy without growth as a resilient and equitable alternative extending goods, services, and credit for people to be redesigned in a new pattern of social existence of adaptability to stagnation as a new norm.

All this demonstrates that another economy is possible, but only in times of crisis, irrespective of who renders it plausible. Diffused communities in the developed world have made it possible through spontaneously emerging institutions, groups, relations and practices, as part of their survival struggle in 2008. A state like Kerala proves its feasibility by means of constitutionally ordained local self-governing bodies, cooperative institutions, and political leadership. Crisis-driven alternative economy’s responses like work sharing, food security measures, basic income scheme and more, do reverse capitalist redistributive functions. Kerala shows how governments must evolve policies of social care-nets, strengthen public health, provide economic stimulus to local enterprises, and combine growth with equity. This hardly means that the feasibility of production, consumption and exchange, not driven by motives of profit and consumerism, is enough to make it last beyond the days of crisis.

Mukulika R is a member of the Editorial Collective at Indian Cultural Forum, New Delhi.