Writing The Quarantine Papers was a febrile experience.

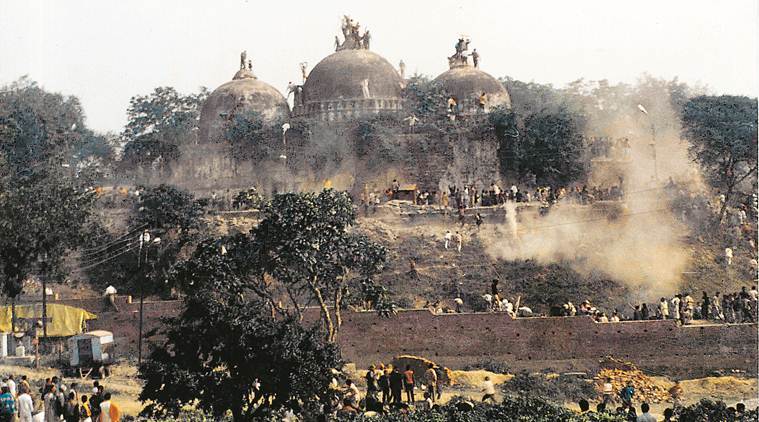

For eighteen years we had waited for the precise context. The outrage, the pain, the despair of 6 December, 1992, had scarred us with the knowledge that India would never be the same again.

The act in itself was criminal. But the malevolence went much deeper than the act. It had divided identity. We were no longer Indians. By our names we were now identified as Hindu or Muslim.

For us this was a crisis.

We shrank from this newly inflicted identity.

We watched our parents cringe and shrink from it. Their generation had fought for Independence, and their pride in democracy, in plurality, had advised everything in their lives. They had raised us in this faith. To watch their world shatter was noxious.

By then, we had known each other for a decade. We had trained together in surgery, and our shared experiences, as much as our bibliophilia, defined our friendship. Looking back, we see that our ease in writing together came from feeling at home with each other from the instant we met. We felt at home with each other’s families too, long before we knew each other well. That came from the similarity of values and etiquette, the wordless landscape of a natural habitat.

Others may have remarked on our widely different backgrounds. We noticed no such difference.

We belonged in that habitat of Indian-ness which, like a mighty biome, nurtured us.

The grief of 6 December, 1992, was for the barbaric destruction of that habitat.

Now it was no longer a wordless landscape. There were signboards everywhere. Warnings, barbed wire.

We had found no words yet, for anger or for grief, when the new millennium began.

Almost at once it was evident that the anarchic brilliance of the past century would change into a mulish conformism, a retreat into medieval constructs of discrimination. Then came the Gujarat genocide. Appalling images of barbaric cruelties perpetrated by ordinary citizens defied any sort of rationalisation. When the dust settled and the facts came to light, it seemed incredible that such psychopathic violence could have been inflicted by Indians on Indians, by householders on their neighbours.

And the nation watched, silently.

Hindutva, an idea cooked up in 1928, was now positioned as Hindu. This construct should have been repugnant to every Hindu in the nation—but somehow it wasn’t. It was a most anti-Hindu ideology, in that it debased every principle of Hindu belief—but nobody said so.

Hate became the new normal.

While our eyes read news reports, our minds were anesthetised by greed and opportunism. There was no outrage, no guilt, and definitely, no pain.

This amorality puzzled us. It led us to question everything.

Naturally, because we are doctors, our questions began with medicine.

The accepted narrative of disease was replete with indiscrepancies and fault-lines.

We discovered that nobody had documented the Indian experience.

It was common knowledge that India was the laboratory for the discoveries that changed medical science in the late 19th century—but not a single Indian appeared in the story. Millions had died with their suffering unnoticed, erased from history books and medical texts. Their lives were unsung. And, what of their experience of illness?

We could, at least, uncover that?

So we did.

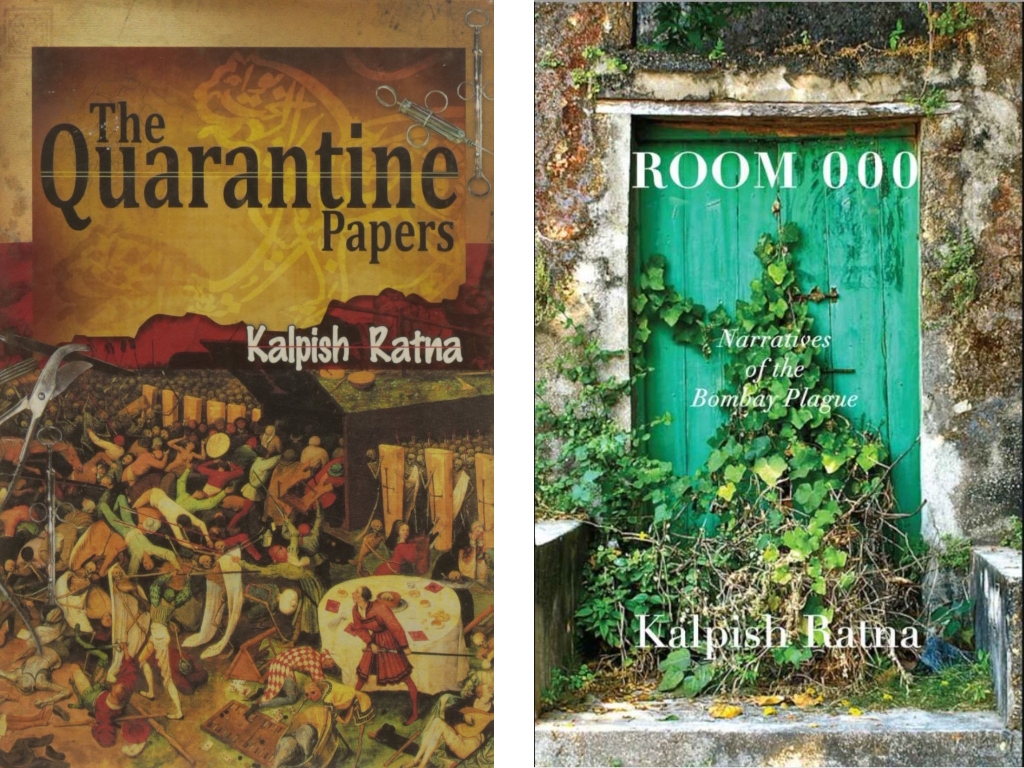

We looked at the epidemics that had ravaged Bombay between 1500 and 1900. In the course of that journey, we encountered the Bombay Plague of 1896 which would become the Third Pandemic of Plague.

Looking back, it seems serendipitous. We encountered the plague not as a solid standard history, but piecemeal. Thanks to the Bombay Archives, we were able to follow the epidemic day by day. Not just through the expected sources of government bulletins, dispatches, patient records, hospital returns, but through personal anecdotes and meticulously documented interviews. We were startled by the inextricable DNA swirl of disease and communalism that made of the plague a twinned narrative. It felt almost as if the disease was a bodily manifestation of the communal hatred that had been building up in Bombay since 1893. We discovered the eerie parallel between events in 1893 and Bombay in 1993. It was as though Bombay was a Möbius strip, twirling and untwirling in a loop through time.

The Quarantine Papers was written almost as an automatism. The dual identity of Ratan/Ramratan Oak emerged under the compulsion of event. The Kipling motif stared us in the face every time we strolled past the J.J. School of Art into Crawford Market. There stood the V.T. Station in all its Gothic glory.

We were living the novel, all we had to do was take notes.

Writing The Quarantine Papers led us to the second layer of investigation—What was the experience of plague like? To the people who survived it, to the victims, to those who escaped it, to the scientists and doctors who showed superhuman endurance and strength? That led us to Room 000. It was while researching this book that we began to understand the hidden agenda of epidemiology.

None of this prepared us for COVID-19.

The first week of February 2020 was like a rerun of the 1896 plague. There was no similarity between the two diseases. Bubonic plague is not transmitted from human to human. COVID-19, as we know, is. Only pneumonic plague spreads through inhaled infection, and these cases were few in 1896. Nonetheless, there are inescapable parallels. In 1896, militarisation of the plague provided the British with a powerful tool to fragment the population.

The population then—like the population now—seethed with communal strife. The growing hold of the Hindu Mahasabha and the Cow Protectionists had vitiated trust and harmony—but nowhere near what we have experienced in these last few years. There was yet, despite our enslavement to the British, an open forum for thought and opinion.

Punishment was not as swift and vindictive as it is now.

Fearless voices rose then, as now.

They were heard then.

They are gagged now.

Fear is the bully’s most effective weapon. The menace of a gun kills before a bullet can. The same is true of COVID-19.

The atmosphere of panic surrounding this virus is unprecedented in the world’s history. And never has humanity cowered in such abject terror, not even before diseases far more lethal than COVID-19.

In India, COVID-19 excavates a very clear picture of how the caste system evolved. An epidemic which once devastated a society left a changed social order in its wake.

“Social distancing” is a very wrong term for a very necessary measure. Unfortunately, the cognomen rather than the measure is in action today. COVID-19 has turned us into a bipolar society of victims and aggressors. Instances of social rejection at every level occur every day. Some overt enough to be reported in the press. But most are “avoid your neighbour” subtleties that will probably become a part of our future. In these six months a corrosion of human values infects us even more than any virus can.

Much of this violence is the primitive response to fear, and we feel the first step to counter this is information. There must be total transparency about what this disease is, and what we are likely to face, and how to face it.

From the beginning of this epidemic in Wuhan, we have been documenting the progression in understanding as scientific data accumulated. Nothing is too remote or abstruse for awareness and comprehension, and since we felt that was imperative, we have written a book about this virus.

COVID-19 will pass.

How will it have changed India?

Much of India’s poor will be dead, not necessarily from COVID-19, but from its outfall.

Disease and death should democratise a society, but history shows us otherwise. We cannot afford the vindictive complacence of fatalism—notice how only the survivors are fatalistic? The dead died hoping, still believing in the goodness of their fellow beings.

We believe that India is bigger than this or any other government or its pronouncements.

A nation is its people, and Indians are not as gullible nor so callous as we have shown ourselves to be. Our young have raised their voices fearlessly. The women of Shaheen Bagh have taught us that resistance is in our blood, and we can have the courage to voice it.

Meanwhile, we need to realise that COVID-19 is not a graph. “Flattening the curve” does not mean flattening our humanity.

We must use this pandemic to learn to be human again, to feel another’s hunger and pain, to extend help and comfort, not shun the sick.

This pandemic can only be overcome at the individual level.

The State does not own your body. You do. Take care of it.

And because you and I share this habitat of Indian-ness, don’t let us destroy it in panic.

Especially, in the time of COVID-19, Jai Hind.