The last few years have violently thrown open the question of what it means to be a Muslim in India. Several filmmakers have tried to grapple with that question. Mulk (2018), Raazi (2018), Raees (2017) are some big Hindi films that come to mind. But each film, despite their pledged intentions to mitigate prejudice, has failingly found itself reiterating them. This is because the films could not connect with the contemporary — the time in which the film was set, made or shown. There is an alarming problem of temporality.

While theoretically, these films vow to depict the present-day reality, their visual grammar is festered in the moth-eaten frames of the 1980s realistic drama. This dissonance arises because these films have misplaced intentions. There is a difference between response and responsibility.

A film is not a book, a political speech or a piece of news. It draws from all disciplines — poetry, literature, anthropology, news, music, art, science, environment, speech, the Internet, and everything around us. However, theoretical foundations constitute just one level of the form. Its elements are the story, plot, the idea, dialogues, the protagonist and the like; i.e., what you say. But a film also rests upon a cinematic (audio + visual) language that complements this conceptual stage. This part makes up the film’s sound, gestures, narrative, the gaze, costume, the secondary character, the psyche, where you place the camera (literally and symbolically) etc; i.e., what you show. The latter is a tough nut to crack, but this is what makes a film a film.

In 2016, Arun Karthick set up a small coffee kiosk in the city of Coimbatore. Soon after, communal riots broke out in the aftermath of the murder of C Sasikumar, the district spokesperson of a Hindu right-wing outfit, Hindu Munnani. Karthick saw his shop being looted and broken down, along with many others. “I saw for myself the fuming communalism that had been brewing,” the filmmaker told Cinestaan. “Even before that, we had been reading about things that were happening in different parts of the country. Now, it showed up in my city and I had seen it for myself. I thought I should be expressing this. The moment I thought of that, I went back to the short story.”

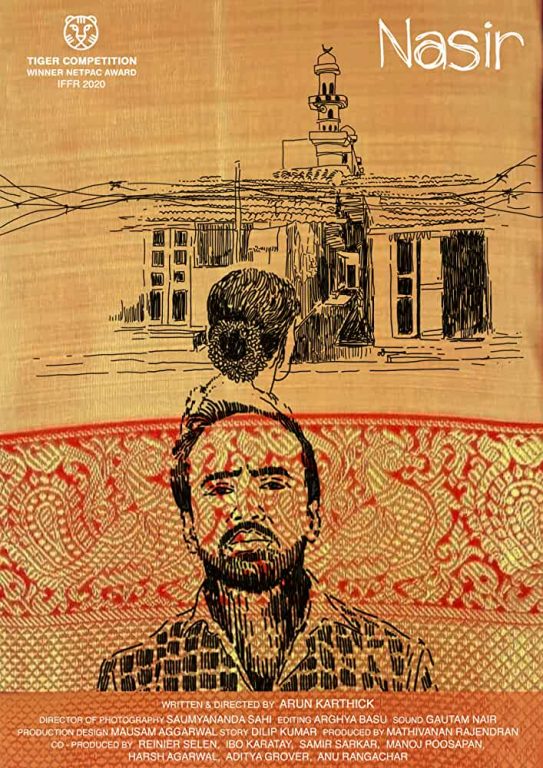

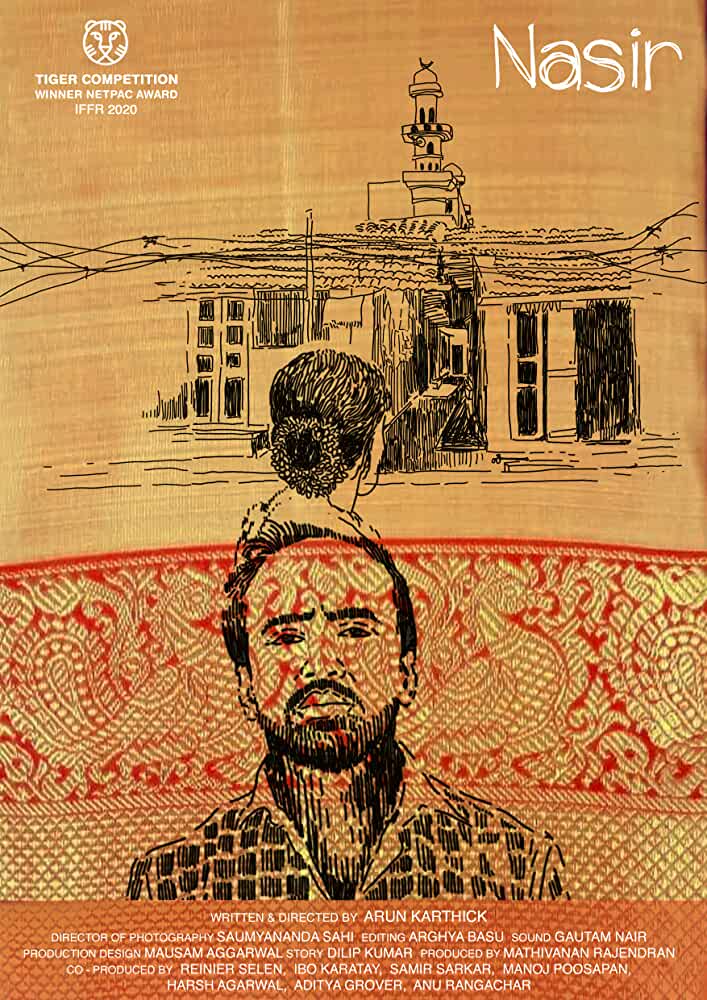

Based on Dilip Kumar’s A Clerk’s Story (c. 1990s), inspired by a horrific true incident of communal violence, Nasir is a film that heroically portrays the precarious existence of a Muslim in Modi’s India. It chronicles a seemingly ordinary day in the life of an ordinary sari salesman in the southern city of Coimbatore, in all its corporeality. Nasir is poetic, romantic, philosophical, and social. Nasir is a Muslim man we need to know culturally and socially. His life unfolds before us, almost as though it is happening in front of us in real time, keenly observed and accompanied. And yet, with all its moments of “rawness”, you can tell it is brave, you can tell it is honest, because in Karthick’s Nasir, morality becomes the form.

Creating a piece of art for the contemporary is a challenge. This is because the present is a unique space, a unique moment in time, that has not occurred before. So sometimes, to be faithful to the occasion, an artist might need to devise or invent a new poetics. This challenge becomes harder when you’re making a film about the Other. Now, not only do you have to overcome and unlearn years of your social conditioning as an individual, but also have to step into his shoes to tell his story. You may even risk letting go of your acquired technique over the years. In order to humanise this Other, you have to see him in your own light. This means that the Other cannot only be spoken about in a language of terror, or victimhood. The Other must also be spoken about through his joys, and dreams. This is where the complexities of ethical representation arise. Unless, an artist has really worked courageously, or empathetically through these questions, his Other will always remain a sceptre, a shadow, an imitation, a skeletal. It will never embody or take a human form. At worst, it will remain a stereotype. This was my problem with Mulk.

The Muslim in Mulk was someone I had already known culturally, but was it someone I knew socially too, in present day India? Every character in the film looked, spoke, moved, ate predictably. They were located demographically and socially in places I’ve seen in films before. I knew that story even before I watched the film. I didn’t need the film to tell me the tale that has been told over and again. The problem with Raees was the same. It was dated. The problem with Raazi was that it picked and chose its battles, it was selective and shrewd.

All these representations bothered me. Is it enough for a film to “have its heart at the right place” and stop at that, even when attempting to address a heinous political moment?

Marathi playwright and academic, GP Deshpande, addresses this question in his book, Talking the Political Culturally and other essays (2009). “Artists, writers and performers would be naturally concerned with the political problems and agendas of the times. Indeed, they should be. But to react to a political situation by itself is not talking or even thinking about the political, culturally. At the hands of a lesser artist the exercise might end up in producing manifestoes and posters or calendar art. There ought to be the political within art.”

Very few Indian films in our recent times have risen to the task of giving the contemporary age its metaphors, and Nasir is one of them. Through the perfect harmony of thought and image in every frame, the film achieves what GP Deshpande hopes for art to do. I have not seen a film like this before, because I have never known about this existence before. It almost heralds a political cinema to come.