“We are supposed to travel – that is how we work. This whole idea of being so attached to one place … I can talk about home and I can talk about my hometown, but would I want to go and live there? No, because I carry it with me.” (Zarina Hashmi, Black Sun, 2013, Devi Art Foundation, Delhi, Curated by Shezad Dawood)

“We are supposed to travel – that is how we work. This whole idea of being so attached to one place … I can talk about home and I can talk about my hometown, but would I want to go and live there? No, because I carry it with me.” (Zarina Hashmi, Black Sun, 2013, Devi Art Foundation, Delhi, Curated by Shezad Dawood)

When I was growing up in Delhi, Zarina was an intimate part of my childhood. One very vivid memory I have of her is when she and my mother, Sarojini, came to pick up my sister, Janaki and me from school, to take us to her barsati. Zarina was living alone now, in Jangpura, in South Delhi. My mother was in the passenger seat next to Zarina in her small red car, waiting for us to come out of school. Zarina was wearing a stylish short kurta with slacks. All in white and black. The image that I can conjure up of her even today is of the colours, black and white and red, and how dramatic that looked.

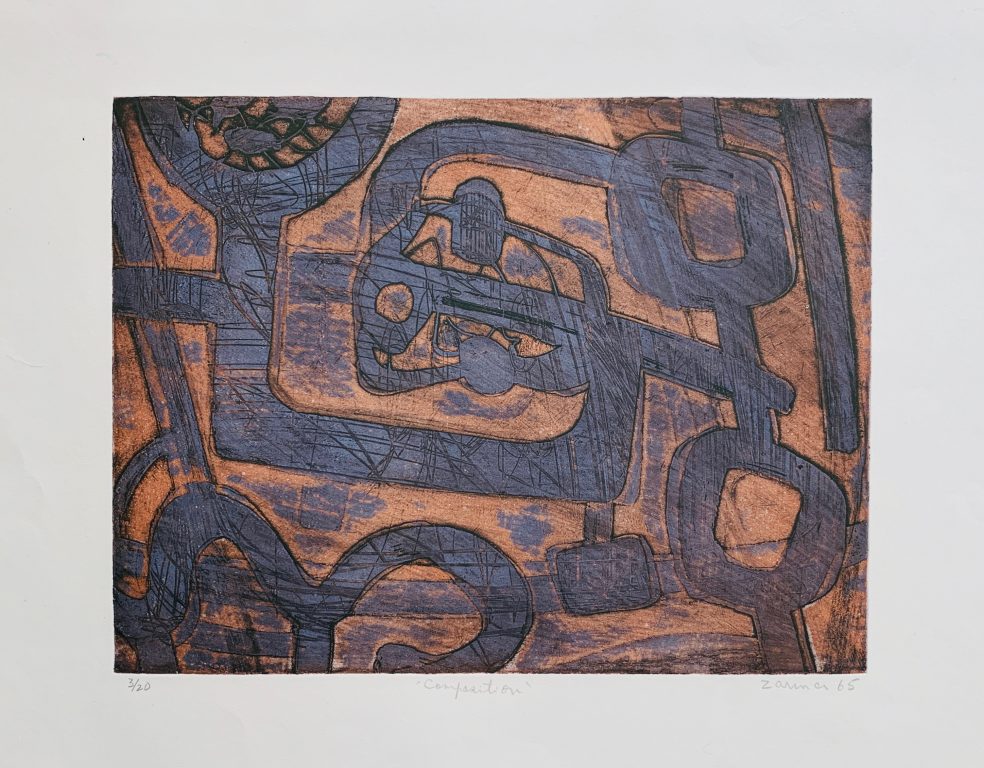

We drove to her studio home, one large room with an attached kitchen, bathroom and terrace and when we entered she wryly tells us “…most people buy sofas for their living rooms, I have a printing press!” How amazing for a child, to see a printing press with its heavy metal industrial form, and that like magic, rolled out copies, prints of images from metal plates, that were carved or etched into; or from silkscreens on large frames exposed by a flash of light. Our job as children was mostly to occupy ourselves while our mothers smoked cigarettes and drank tea and chatted about this and that. So, we sat under the printing press that afternoon, paper and pens and colours in hand, doing our own drawings.

Zarina was this stylish friend of my mother’s. She had a birthmark on her face, as though someone had made a dot with a marker, and she made prints strictly in black and white and maybe silver, and she wore nothing but black and white though there were a few exceptions later as she grew older. And she had strong opinions about what she liked and didn’t like, whom she liked and didn’t like. We did not see her very often because she was travelling to different places across the world, until she finally settled down in New York. My mother once visited her there, and she brought back a description of her apartment, a self-crafted loft-space, in a building full of furriers and next to a fur factory. Zarina was larger than life for us then. She had ejected herself out of middle class existence, to ‘be her own person’ living the life of an artist. Zarina had the will and determination to carve an independent life for herself at a time when artists were asserting themselves to break away and live different kinds of artistic and bohemian lives, but it was not easy for a woman artist.

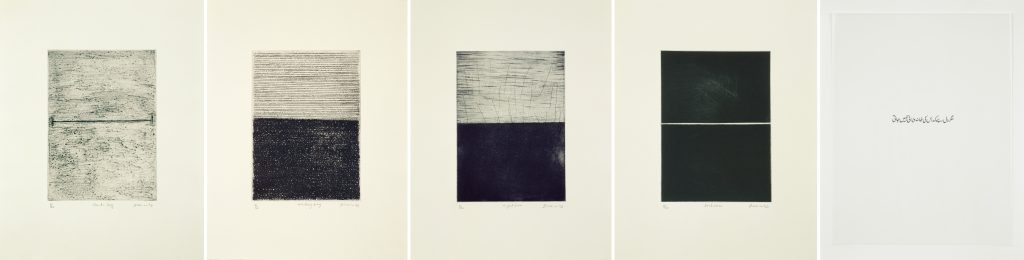

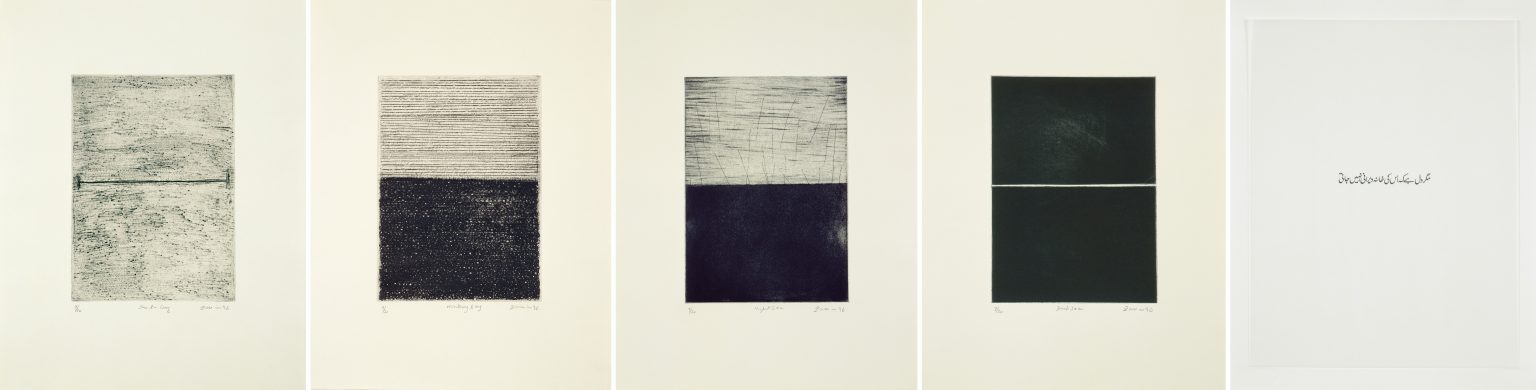

We had a print in our living room that was one of Zarina’s early minimalist series, (Untitled, 1973), and my father, Abu, had bought it at an exhibition in Delhi, possibly in the early 1970s. It was one in a series of silver silkscreens with white broken lines. This print had a curved line that broke as it descended to the bottom of the page. It was a subtle white on silver, and not high contrast, often disappearing into the reflection on the glass that framed it. In her later work that is known more widely, her paper has now become warm; the black like freshly made kajal soot for the eyes; the gold from the gold leaf that decorates precious objects. And the content of her work now included a home that she had begun to crave for – the affection and community life of her large and close-knit family of her childhood, filled with love, humour, and anecdote.

She once told me that she misses the inner quarters for women, the zenana, of her family home in Aligarh, where women gathered while the men wore Western clothes and engaged with the world. A space of intimacy, caring and love, where children were nurtured, vegetables for the next meal were cut, embroidery was an extension of nimble fingers, a garden was tended to and gossip and idle chatter filled languid days and nights. She was torn even as a child between these two worlds, the modern and the traditional one; the outward-looking persona of her father’s world with its books and the culture of reading, and the unconditional warmth and domestic creativity of her mother’s. Hers was to be a life where she would break away from the comfort zone of such a home and a family, to struggle in solitude. But as she aged the craving increased. And this desire to conjure up the warm sensations of home makes its way into her work, so many years later, and so far away from home.

Her apartment on 29th street in Manhattan, a room of roughly 800 square feet, set in a commercial building and on a floor shared with a fur factory, was to become her home away from ‘home’ for at least forty years. Into this space she fitted in her studio, her bedroom and living room for visitors, her kitchen, her bathroom, her archive and storage. As if the entire rambling home of her childhood folded into a small New York loft. This was the space where she lived and worked, beat her paper pulp in a vat, shaped her sculptures, and printed her woodcuts and etchings, embossed her paper. The presence of the fur in the manufacturing unit next to her must have contributed to her asthma and then COPD. And yet she never wanted to leave this nest, this space “to hide in forever”. She passed away on April 25 in London in the house of her niece, and fortunately not alone in her nest in New York.

When my father had bought her silver and white work, the white was an ivory white, the silver an industrial silver. It had a disciplined, geometrical look, if not cold. It may have been inspired by the borderlines that have divided and cut violently into nation-states. But it also represented a minimalism that evacuated the emotional, the sentimental and most certainly the nostalgic. It was meant to stare at you in the present and make you recognize the present. This modern moment was – like a thunderbolt, a fracture, a breakaway from the past. It belonged to an urban world that lifts you from all that comfort and familiarity of smells and touch and spaces that filled your life. Hers became in contrast, a life of minimal needs, pared-down, as she kept her focus on the minimal abstractions of the modern world, the metropolises she explored and lived in as she travelled.

I know that my father often used this work by Zarina to discuss and defend the virtues of abstract art. Like Zarina, he had studied mathematics and believed in the precision of thought and simplicity that was found in spare minimal art, and in Zarina’s work. He shuddered when he recollected how a relative who saw this work hanging on the wall of our living room had described it in a tone of disdain as ‘resembling a broken bathroom mirror in an Indian railways compartment’.

Zarina was my first point of contact in New York when I lived there from the late eighties to the mid-nineties. My mother had found her phone number, which had not changed in years and directed me to call her, to have a support, and a guardian. I was now out of college and in a fog trying to make my way into adulthood as an artist. I arrived to meet her after all these many years with a portfolio of prints I had made as a student in the printmaking department of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda. After a small and simple lunch, she took me to “The Printmaking Workshop”, run by Robert Blackburn, who was a friend to so many artists of ‘colour’ who came from across the globe to shape a life of art in New York City. It had a history of being a print workshop that nurtured many from different backgrounds much like a home and a large joint family. It was founded by Bob who was African American because till the civil rights movement changed segregation laws, black artists could not utilize printmaking facilities used by white artists. Zarina was an old friend of the workshop, she had worked there and taught there, and after she introduced me to it, it became my base from where to find my feet in the frenetic daily life of the City. And I attended the printmaking classes she taught.

And then the rest is history. Zarina took ‘Jitu’, Satyajit, my husband (then boyfriend), and me under her wing. And we frequented her loft at all times of the day and night, for gatherings with other friends or alone, sometimes she had lunch parties with only her women friends and at other times dinner parties where she cooked (how can I forget the chicken achar and tehri!), and invited her favourite inner circle of friends – the creative men and women who lived in New York whom she had met over the years. I met many of my close friends there at her home, people to this day I keep in touch with. This was true for so many of her friends, I think. She presided over Jitu’s graduation (presented him with the series of woodblock prints, an early version, of “Urdu proverbs”, – that hang on our bedroom wall!), our ceremonial visit to city hall to formalize our marriage, and numerous openings and gatherings, always there, always kind, supportive, fun, open and curious. She would make a list of all the galleries and exhibitions she wanted to see on a Saturday morning and sometimes I would join her to see these shows. Her interest in art was eclectic and with the times, and we always had a lot to talk about when we saw art together.

When I returned to India in 1995 I saw her infrequently except for my occasional visits to New York and to Delhi when she had exhibitions at the Espace gallery. I introduced my son, Ishar, to her on one visit and she instantly became one of his many grandmothers and showered him with gifts and playful chatter. I then saw her two years in a row from 2016 after my mother passed away and when I could sit and reminisce about my parents, whom she knew so well. Being in her loft, I could see that it was like she was in a hurry to finish more and more work, I had never seen her quite so prolific before. Collages, folded paper, maps and plans, homes of all shapes and sizes, jaali trellises, tents, borders and lines of control, enlarged prayer beads, black ink and gold leaf, all rolled out as she also went back in time to her own work as in the collages titled Ten Thousand Things, 2009, and to her indelible memories of a pre-partition childhood spent in innocence in Aligarh with her beloved family. The titles of her new set of prints, Home is a Foreign Place were: Home, Threshold, Door, Entrance, Courtyard, Wall, Sky, Earth, Sun, Moon, Stars, Axis, Morning, Dawn, Dew, Afternoon, Stillness, Hot breeze, Evening, Shadows, Clouds, Dust storm, Rain, Fragrance, Night, Darkness, Despair, Country, Dust, Language, Journey, Road, Destination, Distance, Time, Border.

But New York as a city she loved had been changing for her since the years following September 11, 2001. It no longer only represented that melting pot of people who could be lost in the buzz of life, living for the moment, bolstered by opportunity and freedom, warmth and kind generosity. Instead it was now a New York fighting to retain its spirit, its soul and original character from the onslaught of events that had hit it. She felt alien suddenly, not so much personally, but a part of her seemed separated from the streets she had walked for decades, that were so familiar to her, and so much a part of her contemporary existence. She was drawn now to a more spiritual inner life inspired by a Sufism and poetry, that comforted her as the world erupted into unspeakable suffering unfolding daily on television screens in the form of wars and forced migrations across borders. Events that may have reminded her of the earlier traumas of Partition in the subcontinent, and of the time when you were forced to choose between the love of a country and a place, and the love you had for the people you were closest to, who may be across a closed border.

At the same time this was the period of her life when she was finally recognized internationally for her life’s work as a contemporary artist. She had a busy decade of showing in one-person shows, at her gallery Luhring Augustine, New York, a large retrospective titled Zarina Paper like Skin, curated by Allegra Presenti, at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2012, the Guggenheim, New York, in 2013, and Art Institute of Chicago, 2013, among others, and she was in numerous other shows across the art world. In 2013, I was in a group show with her, titled Black Sun, at the Devi Art Foundation, Delhi, where she showed maps of all the cities mired in ethnic conflict. Titled These Cities Blotted into Wilderness, (2003), the series graphically represented aerial views of Grozny, Sarajevo, Srebrenica, Beirut, Jenin, Baghdad, Kabul, Ahmedabad, New York.

I know I thought I was special to her, and I know that she was and will always remain special to me. But so many others felt this way too – among her peers, younger artists, the children of her friends, her nieces and nephews – the list is endless. So now as I feel the profound loss of never again being able to sit on that diwan in her New York loft and just chatter idly about art, the art world, people, our lives, our parents and siblings, I can see that so many are feeling the same way as I feel. She was able to, in her life of solitude and quiet contemplation, reach out to so many and more importantly care for them, show a genuine interest in what they did, touch their lives intimately. With her quiet presence and wry sense of humour, she allowed for this world of people to filter into her life, never allowing it to distract her, always absorbing, always listening, and always voicing an opinion from the heart and mind. As I read the obituaries that chronicle her life, I too wish to pay homage to her indomitable courage and generosity, her creativity and stamina. The life that experienced and embodied so much has passed on, but her work will forever shine with that light of poetic greatness.