Just a few months ago, I visited the JJ College of Architecture in Mumbai to deliver a lecture. The moment I was on the campus, I was surprised by what I saw. It seemed I had entered a premises in Shimla, a town that is not just thousands of kilometres away, but also at an elevation of 8,000 feet above Mumbai. The buildings on the JJ College campus resembled those in Shimla.

Every year, 18 April is marked as World Heritage Day, a day that serves as a reminder to us all to commit to protect historic monuments and consider them our shared heritage. The theme for 2020 is: shared culture, shared heritage and shared responsibility.

This theme is all the more legitimate today, when the Covid-19 pandemic fuels a global crisis. To focus on global unity while a worldwide health crisis unfolds is a way to not just recognise that world heritage is connected with landscapes, monuments, places, but also that it should be valued by all diverse groups and communities.

The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), a body responsible for conservation of monuments and sites all over the world has emphasised that people must realise the importance of sharing knowledge between generations which can promote conservation and protect our cultural heritage.

India holds centuries-old heritage and it must urgently transmit it to its younger generations, and across spaces: this is why the parallel between Mumbai and Shimla is important. And yet it is only one instance of our shared legacy. Indian architecture and monuments speak to the diversity our country holds within it. Architectural forms in the country have encompassed a multitude of expressions over time and space, and in it new ideas have developed as history advanced.

Right from the Indus Valley Civilisation, which is almost 4,000 years old, the inhabitants of this region have imagined cities. The innumerable religious structures built during the Chola, Maurya and the Gupta empires, and during the reign of their successors, especially the Buddhists, have left deep impressions on each other and added to the the cultural diversity of the region. The Ajanta and Ellora caves and the Sanchi Stupa are a few amongst them. Similarly the Sun Temple at Konark, Chennakeshava Temple at Belur, Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebidu followed by the large forts constructed by the Rajput rulers are part of this combined heritage.

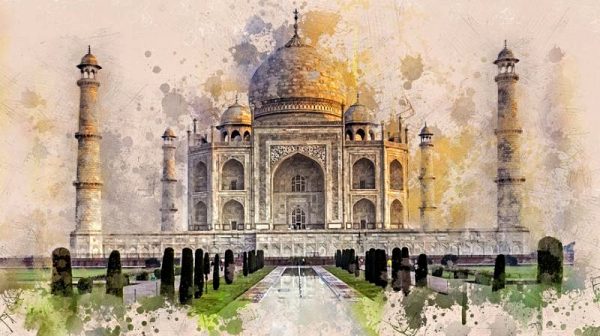

The advent of Mughal period and its influence on the architecture is quite evident. Qutub Complex, Red Fort at Delhi, Fatehpur Sikri, Taj Mahal etc., pose the imbibed heritage of the country and are symbols of commonality. The colonial rule in India by the British and in some parts by the Portugese, left a legacy of magnificent buildings. The development of the Indo-Saracenic style and its inter-mixing with several other styles can be vividly witnessed in the heritage of Indian architecture. The Victoria Memorial and Chatrapati Shivaji terminus are two examples. There are thousands of monuments and buildings that stand today and are part of the common heritage that we all share.

Interestingly, when the British shifted to Delhi and built the Central Vista and Lutyen’s Delhi, they did not impose the British architecture. Rather, as Swapna Liddle, a historian, points out, the magnificent buildings of the Parliament, the Rashtrapati Bhawan, the North and the South Blocks are an admixture of the so called Indian ethos. The red sand stone was used with dome on top of the buildings. Hence, the construction of the Central Vista was an answer to the national freedom movement exhibiting that what the British were constructing is part of the Indian legacy.

But as we celebrated this World Heritage Day, there is a threat to this common heritage and the buildings that have outlived generations together. Is this common heritage valued by multiple and diverse groups? This is for all of us to ponder.

We have already witnessed a vicious campaign to generate animosity towards this shared culture in the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya on 6 December 1992. The fanatics do not want to settle matters there, of course. Rather there are a few more buildings and monuments on their radar and hence we will find a more concerted effort in the years to come for fostering hatred towards a monument or a building, which according to them is not “theirs”.

Sohail Hashmi, an expert on the historic monuments in Delhi describes how the capital city of Delhi had seven different periods of rule. Invariably all of the rulers left a deep imprint on its buildings and monuments. In some of the old forts in Delhi, one monument exposes different layers of brick, mortar and other engineering advancements. Now such monuments cannot be appended to one period, rather, he says, these are part of a conjoint heritage. However, this does not make any relevance to the present rulers and they are bent on reviving the ancient and the mediaeval monuments, which were ascribed to the Hindu rulers and not a mention to the Mughal and British periods.

Interestingly, gist of this feeling can be seen in the NUPF (National Urban Policy Framework) where in the 10 sutras there is reference to the Indian cities and their engineering advancements including monuments and buildings, but not a reference to the Mughal and British period architecture.

In these times, there is a big challenge to this form of historicity, which is not just common but also very diverse. The uniformity that the present rulers want to thrust upon all of us is dangerous for the overall environment in the country. The latest executive attack on this diverse heritage is in the form of redevelopment of the Central Vista (CV) and the proposed changes in the TOD (transit-oriented development) policies. A new parliament is being proposed to be constructed at a time when the country requires more resources to fight the pandemic of Covid-19. The old Parliament, North and South Blocks and the President’s estate are considered as a colonial legacy and hence should not be paid heed to. Rather, the present BJP government wants to spend money on building a new Parliament building along with with other buildings, thus ruining the heritage of the CV and the Lutyen’s Delhi.

I would like to conclude with an anecdote on ‘colonial heritage’. I was Deputy Mayor of Shimla from 2012 and 2017. Shimla town wears a British look for the simple reason that it was developed by them. One of the chief justices of Himachal Pradesh High Court, through a judicial order, pronounced that the city must get rid of the colonial legacy and allowed the use of motor cars to the Ridge. To those who are new to Shimla, it is a mountain town where just 25% houses have access to motorable roads, rest of the city walks or uses pedestrian paths. In some of the important places like the Ridge, the Mall etc., no movement of cars is allowed. The judge said that he will be the first one to take his car to the Ridge and called upon the citizens also to drive through the place. The next day he was the lone car-owner taking his car to the Ridge and not a single citizen drove to that place. This is part of the combined and imbibed heritage that we owe. Later, the High Court order was set aside by the Supreme Court of India.

Hence, the repository of this heritage is ‘we’ the people of India and not ‘they’ the custodians of India. We have to reclaim that right, earlier the better.