The COVID-19 pandemic is the most serious sociopolitical crisis of our lifetimes. In India it resulted in a ‘voluntary’ nationwide curfew on March 22 and from March 25 a three-week nationwide lockdown. While experts agree it will help check the spread of infection, shutting down all social, political and economic activity across the country is unprecedented.

April is the cruelest month, and it will be crucial in determining how well the Indian state is able to respond to the crisis. The Union government’s response so far makes one thing clear: things cannot go on the way they have been. The status quo must change, and the corona crisis lays the ground for creating this change, in at least three ways.

First, the pandemic has brought into sharp relief the shameful inadequacy of public health provision in India.

We are massively short on ventilators: a Brookings report estimates there are only about 57,000 ventilators in the country, not all of which may be working, even though in the worst case we may need up to 220,000 ventilators to cater to Covid-19 patients.

We are also short on personal protective equipment for medical workers such as protective masks, gloves and coveralls. According to reports our requirement could work out to at least 12,500 per day over the next few weeks, while the Union Textiles Ministry is ‘hoping’ to push up production of protective suits to only 8,000 per day, which will only be delivered after 25-30 working days.

It has also been estimated that if the number of Covid-19 patients keeps rising at current rates, 27 of our 36 states and Union territories could run out of public and private hospital beds by the end of May. Medical workers who fall sick due to a lack of protective equipment may not be able to augment our existing capacity.

Let alone medical facilities, around 40% of the world population and 20% of urban Indians don’t even have access to basic handwashing facilities, including soap and water.

These shortages demonstrate that not only are we under-resourced and unprepared for a health emergency like this one, but that even under ordinary circumstances, our public health provision is neither sufficient to serve Indians well nor anywhere close to globally prescribed model standards.

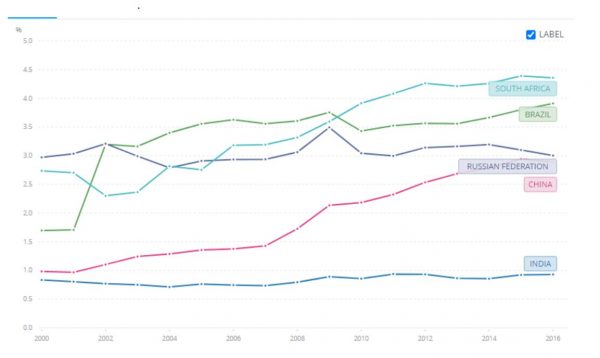

This should not surprise anyone, since India has been spending only about a single per cent of its total GDP on public health since 2000. For the sake of comparison, the corresponding figures for fellow BRICS nations have all been consistently and significantly higher than ours since 2000, as per World Bank data.

Such chronic underinvestment was simply a disaster waiting to happen. That time has come.

Hopefully, there will be an increase in political awareness of the importance of public health and sanitation. We might even see these become election issues in time to come.

Secondly, our administrative assessment and emergency response systems also merit scrutiny.

While the pandemic presents a formidable challenge that has brought some of the richest countries to their knees, there are no two ways about the fact that the Union government’s response to the escalating crisis over the last two months demonstrates a lack of planning that is cavalier at best, and dangerous at worst.

Bear in mind that India confirmed its first coronavirus case as early as January 30, which was also, coincidentally the date that the WHO declared Covid-19 a global emergency.

On February 14 the Union Health Secretary publicly stated, after meeting with health secretaries from states and Union territories and senior officials from Ministries of Shipping, External Affairs, Civil Aviation and Tourism, that the novel coronavirus situation in India was under control.

This was repeated on March 5 by Union Health Minister Dr Harsh Vardhan in the Rajya Sabha: he stated that “the Government is taking all necessary measures to prevent spread of the COVID-19 in India”.

In his suo moto address the health minister also informed the nation that our preparedness and response was being regularly monitored by the Prime Minister and a Group of Ministers comprising the Minister of External Affairs, Minister of Civil Aviation and Minister of State for Home Affairs, Minister of State for Shipping and Minister of State for Health & Family Welfare —as well as being daily reviewed by him personally.

Given that our top ministers and bureaucrats claim to have been monitoring the situation since February, consider how things currently stand.

The situation was allowed to escalate to the point where we needed a nationwide lockdown with barely four hours’ notice and several predictable outcomes, such as the exodus of daily wage migrant workers, a shameful humanitarian disaster that also rendered the objective of disease distancing futile.

There was no clarity over the mode or manner of the delivery of essential services during the lockdown, and the communication of rules regarding the same to the police forces, which led to high-handedness, suspicion and violent clashes between the police and service vendors.

Our testing rates are still among the lowest in the world, rendering our official coronavirus case statistics suspect. The WHO has expressly stated that large-scale testing is the only sustainable strategy of containing the contagion, a claim borne out by the experience of countries with relative success in the same such as South Korea, Germany, Singapore, and Taiwan.

Our narrow testing criteria, as reported by Scroll, are leading to suboptimal use of our testing resources. The number of samples actually being tested is rather lower than even our present capacity.

On top of that we are exporting protective medical gear to Serbia when we face massive shortage of the same, as outlined earlier, and are ourselves trying to import bulk quantities of such gear, as per an NDTV report.

The Union Government did form 10 empowered groups and a strategic task force comprised of 68 senior civil servants to deal with the pandemic on March 29, which is a commendable step, but should this not have been done earlier than a full two months after India’s first coronavirus case detection, 11 days after the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic, and five days after the announcement of the 21-day nation-wide lockdown?

It is fervently hoped that we will be able to contain and limit the pandemic, and avoid the horror stories seen in Italy, Spain, China and the United States.

There needs to be a paradigm shift in our political economy, so as to enable the hundreds of millions of “unorganised sector” workers in our country to have a voice in decisions for which they must bear the brunt.

Over the last few days we have witnessed unprecedented scenes of the hardships that migrant daily-wage workers are facing across the country.

Cut off from their means of livelihood, with no publicly provided safety net, and no means of transportation due to a lockdown from which even state governments seemingly had no warning, hundreds of thousands were forced to traverse hundreds of kilometres back to their villages on foot, with no food, water or sanitation available, at the mercy of police personnel who seemed to be entirely insensitive to their predicament. They chased citizens away with lathis and batons.

Only after a full five days did some state governments institute partial remedies, providing buses to ferry them across different states. The spectre of hundreds of thousands of workers, in the midst of a pandemic, packed tight at Anand Vihar in Delhi and Lal Kuan in Uttar Pradesh paints a picture of administrative disarray, of state governments not being taken into confidence, and of the kind of lazy and tardy planning that can only be summed up as ‘too little, too late’.

The Union Ministry of Home Affairs finally issued instructions on March 29 that migrant workers be quarantined before returning to their homes, and state governments are now jostling to arrange for meals for the workers that stayed behind.

It was only on March 26, the third day of the lockdown, that the Union Finance Minister announced a relief package of Rs. 1.7 lakh crore for migrant workers, the urban and rural poor, and for health workers. Reports and experts suggest that a large portion of this sum (which amounts to just 1% of GDP) includes pre-existing schemes, payments that were already due, and payments that will take too long to reach the people who need them.

The impression one gets through the unfolding crisis is that the Union government did not imagine the consequences of the lockdown on poorer workers at all. This is a very difficult time for the Union government, but shouldn’t we be asking why they had no contingencies in place for the nearly four crore seasonal migrant labourers? Why were they reduced to afterthoughts, fit for only inadequate doles and delayed hand-outs?

This is not the first time that a sweepingly disruptive executive decision of the current Union Government has uprooted the lives of working Indians. The disastrous demonetisation exercise of 2016 is estimated to have caused 60% job loss and 47% loss of revenue among small scale traders, shops and micro industries in its immediate aftermath, as per a study conducted by the All India Manufacturers’ Union (AIMU) cited in an Indian Express report.

The hurriedly pushed GST reform of 2017 hurt informal enterprises, by curtailing their competitiveness and shrinking their profits, as explained in this LiveMint report.

The clampdown imposed upon the Kashmir Valley in the aftermath of August 5 cost the erstwhile state’s economy between Rs. 14,295 and Rs 17,878 crore, as well as 496,000 jobs over four months, as per a Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industries report.

Isn’t it ironic that the unorganised sector, which employs 90% of India’s 500-million strong workforce, is seemingly never accounted for in some of the major policy decisions over the last few years in the world’s biggest democracy?

Their erasure from the public sphere will not, must not, be tolerated any longer.

This pandemic has caught us woefully out of sorts, but it has also given us clarity over which things are important and bind us all across the planet together—and which things are trifling in the larger scheme of things.

When the worst is over, it is hoped that the new normal will be one that sees a genuine populist response, which sees electoral mobilisation along class identity and concerns rather than the now-hollow considerations of religion and caste.

A new normal, where it is legitimate to question not just class underrepresentation, but the fundamental social, political and economic structures and institutions that bring about class.

It is maddening after all, that we live in a society where a few weeks’ economic shock can render tens of millions helpless and destitute. When all of this is over, will we allow things to stay the same, or will we usher in real change?