Norwegian artist and researcher Sissel Tolaas’s artwork at the second edition of the Kochi Muziris Biennale had garnered immense attention for bringing her expertise in “olfactory art” to the festival, through a striking installation of a collection of ballast stones that smelled of the sweat of workers. A smellscape, these stones collected from the waters around Kochi, evoked in those who touched, felt and got a whiff of them, the tales of the coastal city’s dock workers and their “labouring bodies”. It was as much a celebration of Kochi’s maritime past as it was of all those labourers who had contributed to its making.

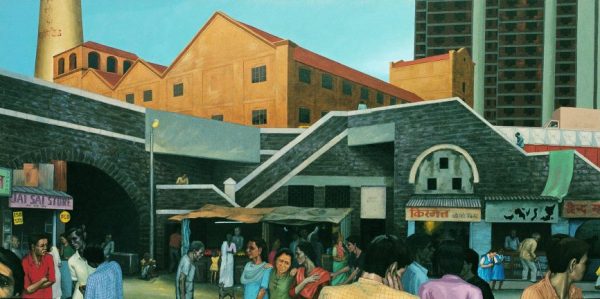

It’s a similar sensory experience to journey through Sudhir Patwardhan’s repertoire of political art — accounts of an urbanscape in transition and the sheer hard labour of those who contributed to making the space. Sweat, toil, factories, mills, smoke, soot and workers’ bodies are what populate his urban realist art. For the last five decades, 71-year old Patwardhan, a painter and radiologist, has been a chronicler of urban life, precisely that of Mumbai’s — its transformation into a gleamy metropolis and subsequent contradictions. While his 1981 work “Street Play” — created in the run up to a mill workers’ strike that took place the next year — is a documentation of the city’s spirit of resistance, his “Lower Parel” describes the story of the now defunct textile mills of the city, placed within an air of melancholia.

Saacha (The Loom, 2001), a 49-minutes long documentary by filmmaker-duo Anjali Monteiro and KP Jayasankar, too tells the story of the decline of textile mills and with it, the end of the work culture associated with it, through “different artistic registers”. Cinema interlayered with the poetry of Marathi poet Narayan Surve and Sudhir Patwardhan’s paintings, it’s a polyvocal work told through the memories and life stories of these two stalwarts of Bombay’s politico-cultural resistance scene and trade union movement, as it existed till about the eighties. Patwardhan, facing the camera, starts off by describing his experience in ’70s Bombay and how he began transmuting the lives of the city’s ordinary workers onto paintings. He keeps talking and the scene slowly fades into a montage of everyday footage from Bombay’s urban life itself, as background score slips into a portion from S D Burman’s “Sar jo tera chakraye” (Pyaasa, 1957), one of the many Bollywood ballads written about the city. These scenes, interspersed with Patwardhan’s paintings, are of a lone man in an old coffee shop, water tumblers, a steel tiffin box, droplets on a restaurant table, reflection of the city on a chai cup, people running for a fast-passing suburban train — all of it as attempts to invoke the extraordinary in the mundane, as we hear Patwardhan speak of working class life in the background. In fact, the documentary starts with the monotonous rhythms of both the local train and the loom in the background — discoveries that were the soul of Mumbai’s modernity — a metaphor for the humdrum of working class life itself, perhaps. Patwardhan goes on to explain the evolution of his relationship with the city and describes an ‘80s Bombay which was class conscious, as also politically aware of the capability and role of the working class in the struggle for their own emancipation.

The relationship between Mumbai — the birthplace of India’s working class movement — and trade unionism began way before, somewhere around the 1920s. Mostly male migrants from North or South India, rural western Maharashtra or the Konkan coast, textile mill workers were largely concentrated in an area in central Bombay. This area grew into a distinct mill district, due to the sheer number of mills it contained, called Girangaon (‘Village of the Mills’). Their existence here, however, was on a precarious plane, owing to extremely low wages and insecure employment. With the growth of the labour movement and the radicalisation of the workers there, it’s understood that Girangaon too grew from simply a geographical space to a political entity. Filled with jerry-rigged shacks and closely built chawls wherein these workers were made to live, the physical structure of these mill districts, and subsequent social organisation and relations between its inhabitants, is said to have had a significant role in their politicisation. The contribution of chawl committees in the mobilisation of workers for general strikes was not inconsequential. Such densely packed housing fostered a sense of community and a collective identity (Mumbai Fables, 2010). However, Girangaon no longer exists in the way it used to and a new metropolis has taken root over its demise, leading also to the consequent “invisibilisation” of its makers. The 1982 general strike led to the closure of the textile mill industry which left scores of workers unemployed. This process was also hastened by a streak of “independent” trade unionism led by the likes of Dutta Samant – marking the ‘death of ideology’.

Monteiro and Jayasankar, the makers of Saacha, too have migrant origins, and they too feel a deep sense of loss for such proletarian spaces “edged out” of Bombay’s face. The metropolis, for them, was built over multiple erasures (A Fly in the Curry: Independent Documentary Film in India, 2010). Saacha, therefore, is as much a personal story of its makers as it is of its protagonists. As fifth generation migrant inhabitants of a city under transformation, it’s also an inward journey.

The film is peppered with songs by Anna Bhau Sathe (1 August 1929 – 18 July 1960), communist folk poet and a part of the radical cultural-activist trio of working class Bombay — the other two being, Amar Sheikh and D N Gavankar. Sathe and others performed where communists of Girangaon held meetings and contributed to the making of this region’s peculiar working class culture. Gyan Prakash says that it was the nature of this specific urban political culture that was altered and refashioned with the triumph of the Shiv Sena here (Mumbai Fables, 2010). Cultural activists like Sathe also performed in public spaces between the chawls, where people gathered, thus radically engaging with Girangaon’s residents and their politicisation.

In the heights of Mumbai

Malabar Hill, a paradise

The abode of the rich

Abounding with pleasure

And here those living in Parel

Working day and night

Surviving by the sweat of their brow

(‘The Song of Mumbai’, Anna Bhau Sathe)

In essence, Saacha is about the progressive and Left-wing culture and spaces that grew alongside the growth of trade unionism in Bombay’s textile mills in, and their tragic demise in the ’80s. We see striking shots of deserted looms, coils of cotton, and spindles, almost throughout the length of the documentary. For Monteiro and Jayasankar, it was important to tell the story of the loom, because Mumbai itself for them is a collection of “antinomies” and contradictions woven together to make a whole, a fabric — the weavers having been the textile mill workers (A Fly in the Curry: Independent Documentary Film in India, 2010). The montage of multiple frames from the city, all put together to tell us its story, seems to convey just that. It also raises crucial questions about the role of art in resistance, and the dilemmas the city’s Left-wing trade union movement faced as it stared at its degeneration towards the eighties.

Patwardhan continues to speak as we go on in the film and he ends it by telling us of his struggles and attempts to make his artwork relatable to the very class it seeks to represent. Saacha too is involved in an effort to do that. As the progressive trade union movement collapsed, the grand narrative that held the city together – which made it possible for Patwardhan to do what he did – fell off, says he. As an eulogy to the lost city, the film’s last shots are those of swanky TV sets in what seems like a newly opened store in the changed metropolis, all displaying the same scene over and over again. The end note is however optimistic, for in the background of these shots is poet Surve’s resistance poem – “How will it do to sit quietly at this hour? So I got up, got out of the slums, Whispered into the ears of the factories, “We got to move ahead now” – laying bare once again, the city that exists in contradictions and layers.

Saacha has travelled the world and continues to do so. It is freely available for the public on YouTube. An installation based on the film was displayed at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2018. The film is also a part of ‘Giran Mumbai‘, an audio-visual web archive, put together in memory of the mills of Bombay.