The process of updating the National Population Register (NPR) begins in April, 2020. That is less than two months from now. We know that the NPR, is the first step in making a National Register of Indian Citizens (NRIC). The widespread protests against NPR-NRC continue, and a number of state governments have opposed the NPR-NRIC process.

What is the central government’s response? It claims the NRC has not yet begun, and that the rules have yet to be framed for the NRIC. But it has failed to deny the link between NPR and NRIC. It has also failed to deny that the NRIC exercise will convert a large number of Indian residents to “doubtful” citizens because they cannot provide documentary evidence to the satisfaction of the local administration.

What will this “verification criteria” be?

The Assam NRC exercise serves as a guide to the principles that may be used in the all-India NRIC as well — while keeping in mind that the Assam NRC was a different exercise and essentially run by the Supreme Court. In the Assam NRC, proving citizenship required producing documents related to birth, property, permanent residence, or education. The document had to be from before the announced cut-off date — 21st March 1971. A person whose name did not appear in a document before 1971 had to produce two kinds of documents. The first was to prove that one of their ancestors had their names in one of the required documents dated before 1971. The second, a document proving relationship with that ancestor. If we generalise, it means that there would be certain cut-off dates, the person concerned would be required

a) to produce documents that shows proof of birth date satisfying the cut-off dates, and the place of birth

b) to provide documents proving relationship to ancestors, and his or her documents listed as valid for proof of citizenship.

As clear from the Assam NRC exercise, none of the documents we consider valid for proof of identity—Aadhaar, Voter ID, or even passport was deemed proof enough of citizenship.

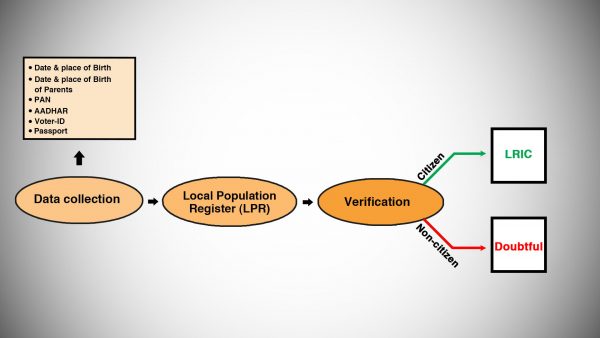

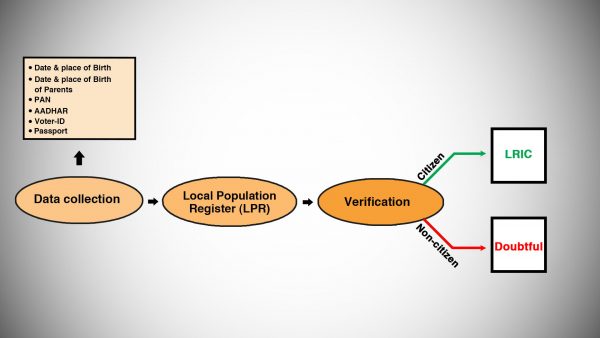

We have converted the various provisions of the Citizenship Amendment Act to create an infographic to show the complexity of the process; and the various hurdles for residents of India to prove citizenship. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has laid down that the onus of proving we are citizens is on us, not on the state. This is what has converted the process of proving citizenship as one of passing a large obstacle course. Any failure at any obstacle would then designate the resident as a doubtful citizen. And the success or failure will be at the whim or fancy of the local petty bureaucrat. This process describes how any person who is a resident and therefore already registered in the Local Population Register will be moved into two categories of residents, one who satisfy the various criteria for being an Indian citizen, the other as Doubtful as citizens, a kind of stateless limbo.

What are the criteria for citizenship in India?

How does one prove citizenship in India? Citizenship in India is governed by the provisions of the constitution and the Citizenship Act. The criteria for citizenship are not uniform for people of all age groups.

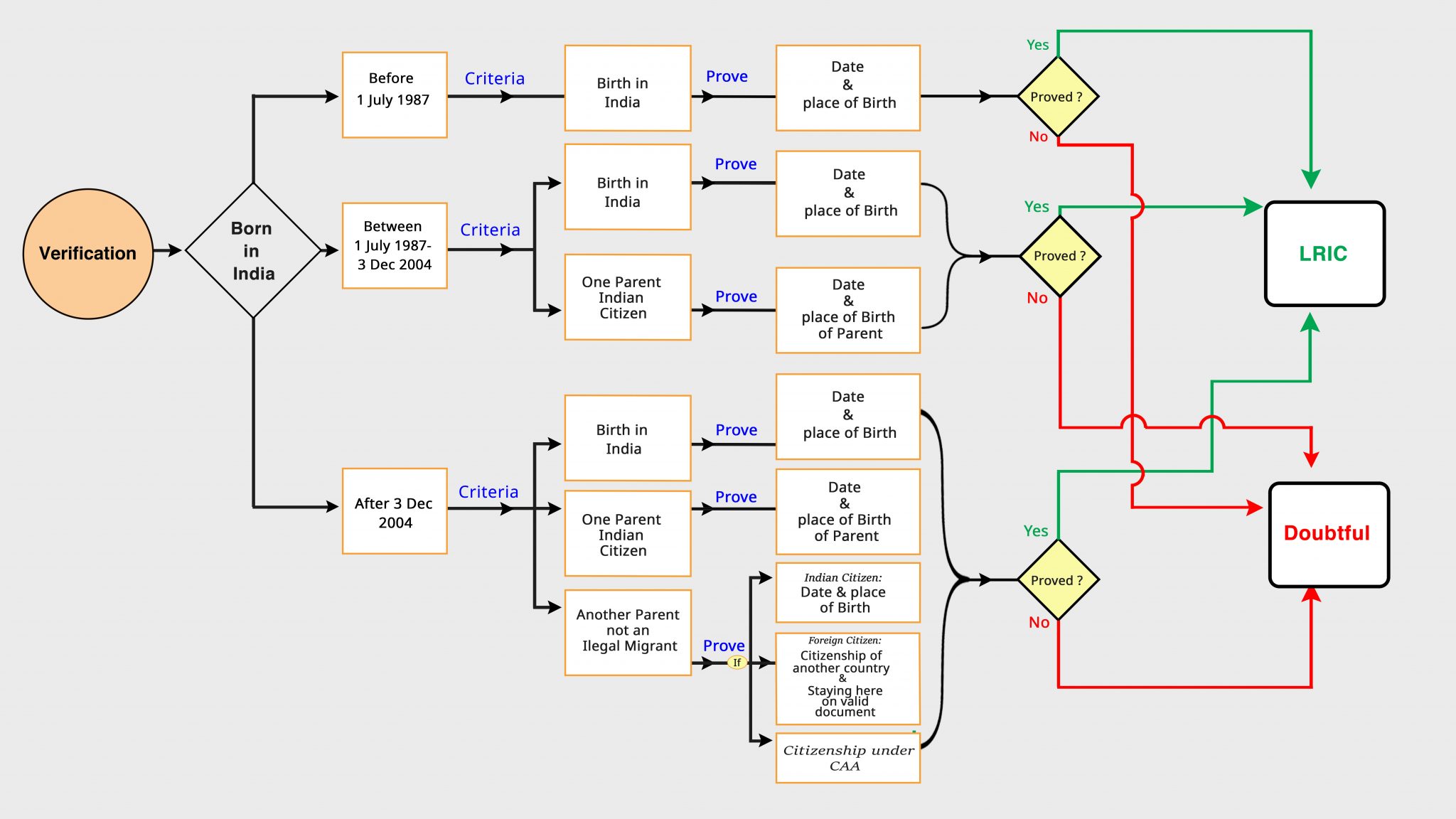

The Citizenship Act, originally enacted in 1955, provided birth in India as the criteria for acquiring citizenship. However, the provisions were modified by subsequent amendments in 1986 and 2003. The graphic below explains the citizenship criteria according to the year of birth and the kind of documents or the proof that may be required.

Born before 1st July 1987

For anyone born in India before 1st July 1987 the criteria for citizenship is birth. A person falling in this category would need to furnish proof of date and place of birth to prove citizenship.

Born between 1st July 1987 and 3rd December 2004

A person born on or after 1st July 1987 and before 3rd December 2004 is a citizen of India if-

- They were born in India, and

- One of their parents is a citizen of India

Anyone falling in this category would need to furnish details of date and place of birth for themselves, as well as, for one of their parents.

Born after 3rd December 2004

Any person born after 3rd December 2004 has to satisfy three conditions to become a citizen of India:

- Birth in India

- One of their parents is an Indian citizen, and

- Another parent is not an illegal migrant.

A person in this category will have to furnish proof of citizenship status for themselves and for both the parents. The proof required include:

- Date and place of birth, and

- Date and place of birth of one parent who is an Indian citizen

- Other parent is a citizen or not an illegal migrant.

Illegal migrant defined under the citizenship act, as amended in 2003, is a foreigner who has entered India without valid documents or has stayed in India even after the expiry of the documents.

To establish that the other parent is not an illegal migrant, the parent could be:

- A foreign citizen with proof of citizenship of another country along with valid documents for entry and resident status in the country

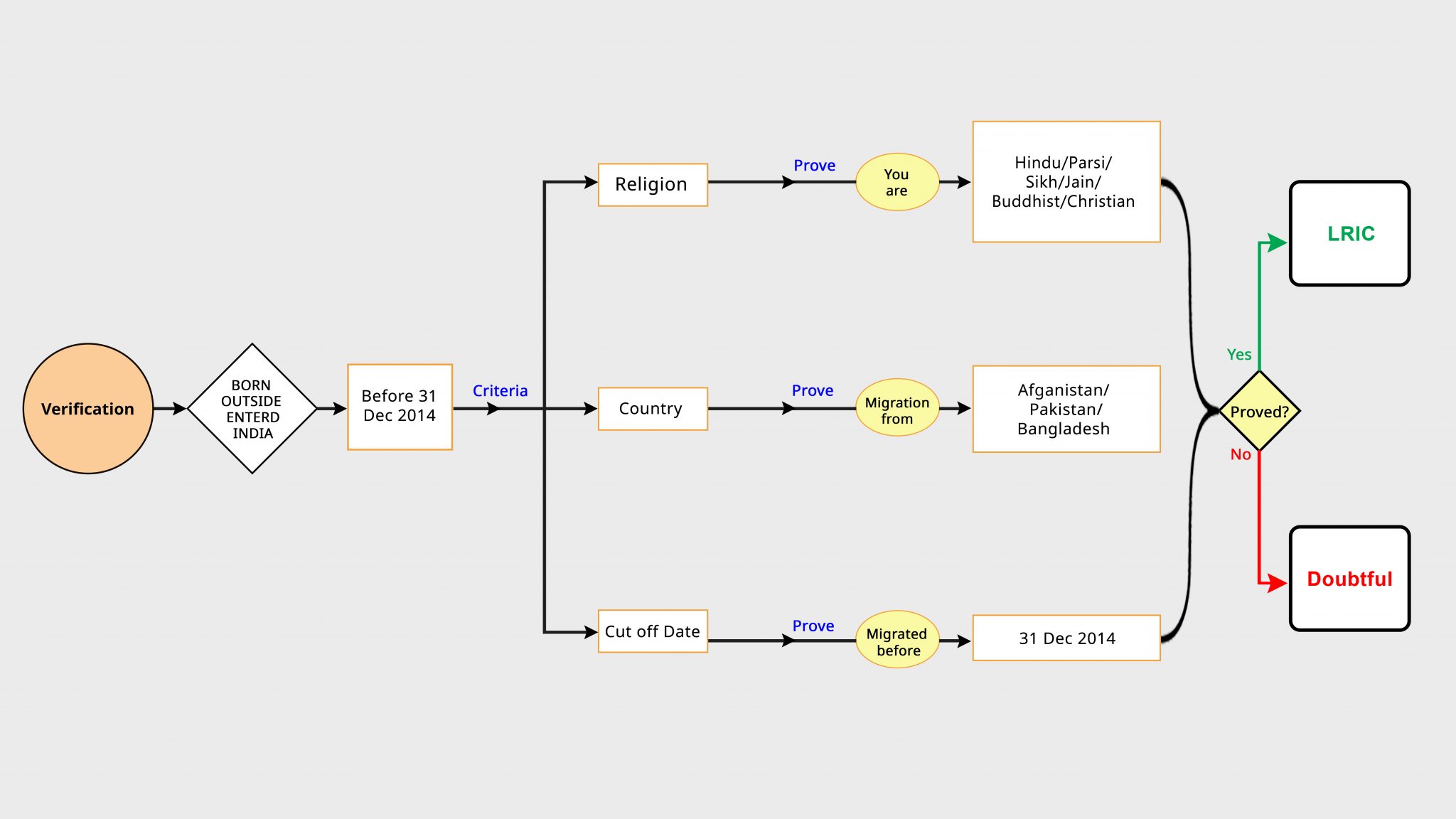

- If the parent is not an Indian or foreign citizen, they will not be deemed as illegal immigrant under CAA by establishing:

- Religion: Hindu, Sikh, Parsi, Jain, or Christian

- Country of origin: Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan

- Migration to India before 31st December 2014

The graphic below explains the criteria for citizenship under CAA and the proof that may be required for it.

If successful in furnishing the proof that satisfies the local authorities, they may be added to the Local Register of Indian Citizens, the smallest unit of NRIC. If one fails to furnish the proof they will be classified as ‘Doubtful.’

The burden of proving citizenship will be most difficult for the young. Documents will have to be furnished not only to prove their citizenship but also citizenship of their parents and grandparents. For example, if a child was born in 2014 and her mother was born in 1992 in India and father in 1989 in India. It will have to be proved that this six-year old child has proof:

- Of her date and place of birth.

- Date and place of birth of her mother and date and place of birth of one of the maternal grandparents.

- Date and place of birth of the father and date and place of birth of one of the paternal grandparents.

Documents

How does one prove date and place of birth? The only definite document is a birth certificate. The level of birth registration in India was only 56.2% even in 2000 and the level is likely to be much less before that. States such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar had only 60.7% of birth registration as late as 2016.

One doesn’t have to go too far to understand what horrors the process of producing documents and proving lineage may bring. Experiences from Assam NRC reveal that certain groups and communities are at a disadvantaged position in such an exercise. Of the 19 lakh excluded from the NRC in Assam, the majority are women. The disadvantaged position of women because they did not have documents to prove lineage to paternal families. Many children have also been excluded from the Assam NRC.

People working in unorganised sector have no access to education, do not own properties and lack permanent residence, as they migrate from one place to another in search of work. How will they produce documents? Imagine the added burden of leaving work to gather documents and attend hearings before the local authorities. How does a daily wage labourer survive and take care of family if she cannot go for work but runs around government offices to get documents?

The exercise would, thus, lead to persecution of all economically and socially marginalised communities.

Arbitrary denial of rights

The verification process will be carried out by a lower level administrative officer. This is an added reason to fear the process, as the local officers may not have proper legal and judicial understanding. A question of citizenship status of any person is of legal nature and the authority to decide such a significant question should not be given to bureaucratic authorities who may not have understanding of the law.

While there is no clarification about the verification criteria by the government, there is impending fear that any criteria are likely to be misused by the authorities carrying out NPR-NRIC. In a recent case in Haryana two sisters were denied passports by the passport authorities. The officer claimed that girls are Nepali merely based on their physical appearance. In another incident in Bengaluru, about 100 makeshift houses were demolished by the municipal authorities, as there was a rumour that migrants from Bangladesh lived in those houses. This action was taken without following any due process, merely based on a video shared by a local BJP MLA. In both the cases the government authorities were guided by bias and misinformation which led to arbitrarily denying people of their rights. These are glimpses of what chaos NPR-NRIC could bring.