On 10th January 2020, a massive number of theatre artistes, musicians, singers, dancers, and directors took part in a Long March taken out from Rashbehari Avenue to the Academy of Fine Arts in Kolkata, in protest against CAA, NRC and attacks on agitating students across the country. Despite their ailing health, this group included acclaimed theatre-performing artists like Paran Bandopadhyay, Bibhas Chakraborty, Meghnad Bhattacharya, and more, with placards that read:

The stronger the ties, the more they will break,

The more the eyes are bloodied, the more they will redden

This is to support the students’ movement right across the country

Organised in solidarity by a united body of theatre workers.

Meghnad Bhattacharya (68) said, “We had decided to organise this protest march together. It had a tableau with youngsters signing Tagore, Salil Choudhury and Kaji Nazrul Islam. It was a wonderful and peaceful procession defined by peace and harmony. After we reached the complex of the Academy of Fine arts around 4:30pm, there were speeches by scholars of theatre, followed by songs, as well as a performance based on an excerpt from Rabindranath Tagore’s Rakta Karabi, by Seema Mukhopadhyay’s theatre group Rangaroop. The Academy holds a special place amongst us, because we have been performing theatre here for several decades. It is an inseparable part of our lives.”

“Peace and harmony should prevail. People should not be discriminated against on the basis of religion. I wished to stand beside these students and wanted to provide them with all kinds of assistance. We had gathered there to stand against this division that the ruling party is creating”, said veteran actor Bibhas Chakraborty, perhaps the senior most member of the collective.

Such acts of protests by theatre artists in Bengal are not new. In fact, for years, theatre in Bengal (divided or not divided) has often been the epicentre of resistance, in terms of the subjects chosen, as well as the places chosen for performance — as part of which theatre was taken out of enclosed proscenium spaces and brought onto the streets, merging into and interacting with the audience. Here’s looking back at a few such groups and personalities.

Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA)

The cruel jolt of the Second World War (1939-45) with famines and starvation deaths in the country on the one hand and colonial repression in the wake of the Quit India Movement (1942) along with the aggression of fascist powers on the Soviet Union on the other, worked as a trigger that awakened the collective conscience of the Indian middle classes. In such a context, the All India People’s Theatre Conference took birth in 1943 in Bombay, under the auspices of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). The Conference aimed to use the stage the crises in Indian society and polity. The Conference went on to set up not only an all-India committee with N M Joshi, General Secretary of the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC), as its President, but also other provincial committees in Bengal, Punjab, New Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

Also Read: Anglo Indians and their marginality

IPTA was formed during the Quit India Movement in 1942. Upon its formal inauguration in 1943-44, the collective took upon itself the challenge to bring theatre to the masses with an objective to build awareness about social responsibility and national integration. IPTA soon became a cultural movement and swept the length and breadth of the country. The collective brought about a sea change in the existent notions about theatre in India.

Soumyajt Majumdar, an independent film and theatre artist in Kolkata pointed out how the new movement of the ‘40s was reflected on a wave of realistic performances in the field of theatre, music and cinema. The most important among them, according to Majumdar, were the plays Nabanna (New Harvest) by Bijon Bhattacharya, Naba Jiboner Gaan (Song of New of Life) by Jyotirindra Moitra and the film Dharti ki Lal (Children of the Earth) by KA Abbas. The common thread connecting all the three was their vivid portrayal of stark reality of the toiling masses in the country.

Nabanna was a turning point in the history of Bengal’s cultural movement. The play, directed by Shambhu Mitra, depicted in four acts the grim tragedy of the Bengal peasantry during the 1943 famine. The famous savant DP Mukherjee of the Lucknow University pointed out that till then he had only “imagined the presence of social realism in art”, but that after watching the play, he was full of hope for the future. IPTA, through their performances, brought about nothing short of a revolution in terms of how theatre was understood by society till then. Theatre, thus, was refashioned into a weapon of and for social transformation.

It left a lasting impression by converting arts for mere entertainment’s sake into a means of expression for people yearning for freedom, socio-economic justice and a democratic culture in general.

“Third Theatre” and Badal Sircar

As a playwright and director, it was Badal Sircar (15 July 1925-13 May 2011) who developed a new form, structure, aesthetics and philosophy in theatre called the “Third Theatre”. The kind of performance that recognizes and continuously seeks to establish maximum intimacy between the actors and spectators, Sarkar’s strategy appeared initially simple and uncomplicated. However, behind the apparent simplicity was a philosophy that made theatre an art for the people, of the people and even by the people. Sarkar began by performing in small halls, but soon moved to the streets and public places, turning the whole world into a stage. He drew theatre out of the binaries of folk and urban, into a “third” space to expose us to an unconventional theatrical dimension of free theatre, courtyard productions, and village theatre.

Also Read: Who is an “outsider” in West Bengal?

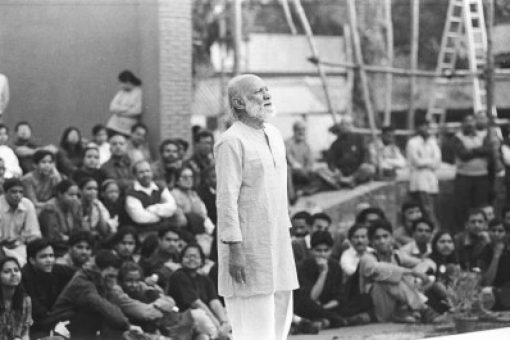

One 1973 afternoon at Curzon Park, opposite the Governor’s House in Kolkata, Badal Sircar and his group, Shatabdi, exposed Kolkatans to an unconventional theatrical dimension. “Free theatre. No tickets, no government grants, no industrial sponsors and wealthy patrons,” he underscored. Curzon Park soon became a regular venue for his group, for easy accessibility and strong political content drew large crowds. Around 1974, Sircar’s book, Third Theatre, appeared in bookstalls.

Utpal Dutt

Utpal Dutt strode like a colossus over the realm of Bengali theatre, staging one production after another and at the same time trying to evolve a comprehensive theory of epic theatre which the thespian hoped should serve as a model for others.

Utpal Dutt, closer to Stanislavsky’s theatrical tradition, aspired to raise his theatre based on the power of myths, while others like Bertolt Brecht formulated their vision by subjecting myths to question. In all his productions, Utpal Dutt achieved just what he wanted to: “Reaffirm the violent history of India, reaffirm the material tradition of its people, recount again and again the heroic tales of grand rebels and martyrs.”

In 1990, at a theatre seminar in Lancaster University, Dutt spoke about the symbiotic relationship between theatre and politics, and lamented at the inadequate portrayal of the exploitative nature of religion.

Dutt was a lifelong Marxist and an active supporter of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). His left-wing “revolutionary theatre” was a new movement in modern Bengali theatre. Fearing the effects that his radical play Kallol (Sound of the Waves) could have on the masses, Bengal’s Congress-led state government in 1965 imprisoned him for several months together. Kallol was based on the Naval Mutiny of 1946 and had ran jam packed shows in Calcutta, and turned out to be his longest-running play at the Minerva Theatre.

Soon the group was called “People’s Little Theatre”, as it took on yet another novel direction their work moving closer to the people and thereby playing an important role in popularising Indian street theatre. The group he started performing at public spaces, before enormous crowds, without any aid or embellishment.

He carried on from one experiment to the next, not once moving away from his belief in the need to merge politics, literature and theatre.

Conclusion

Bengal’s theatre of protest against an oppressive system seems to have waned in recent times with the focus shifted from political to sociological issues or to subjects drawn from literature. This could be interpreted as a result of a fascistic rule at the Centre that controls resistance of any form — cultural or political — and tries to suppress it violently.