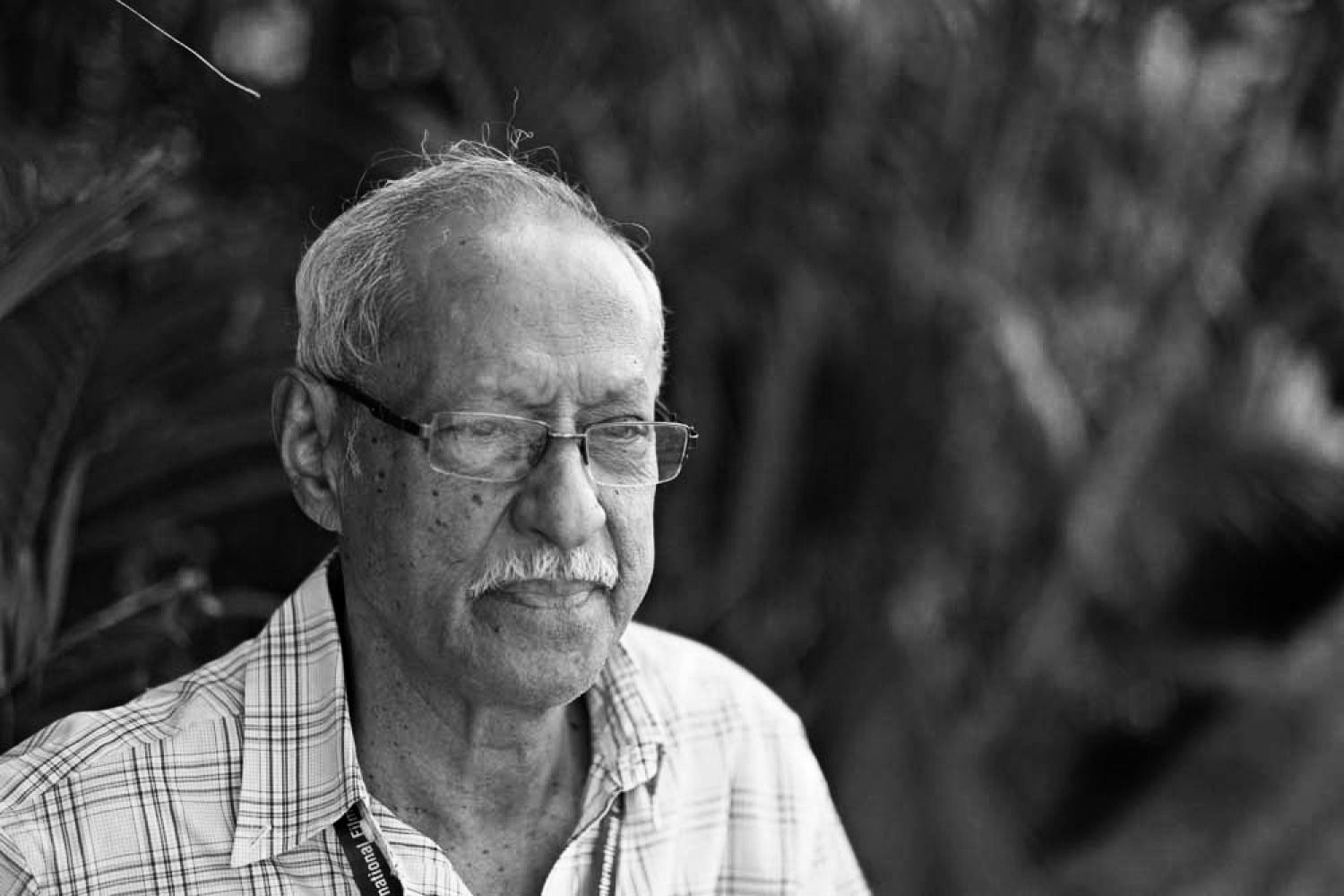

Ever since the police team at investigation on the murders of Narendra Dhabolkar, M M Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh came across 74 year old Konkani writer and activist Damodar Mauzo’s name on Hindutva group Sanatan Sanstha’s ‘hit list’ last year, he has been forced to live accompanied by escort security round the clock. Mauzo’s has been an active voice from Goa against Hindutva and has also been a constant conscience checker of the coastal state and its people, whom he speaks of with immense affection. In 1983, he won the Sahitya Akademi award for his work Karmelin, a Konkani novel set in a village in South Goa.

Mukulika R of the Indian Cultural Forum spoke to Damodar Mauzo about his new book, Ink of Dissent: Critical Writings on Language, Literature, and Freedom, Goa’s identity, life under constant police supervision and more.

Mukulika R (MR): Let’s start off from your home. You were one of the spokespersons for retaining Goa’s distinct identity during the historic 1967 Goa Opinion Poll referendum. How crucial is it to hold onto regional identities in the present atmosphere which seems so hostile to them?

Damodar Mauzo (DM): Right from my younger days, I was an active participant in all battles for my regional identity. By ‘region’, I refer to the real geographical unit that remained colonised for centuries. But it has been much more than that too, as my Konkani identity has remained equally important for me. The Opinion Poll of ‘67 was indeed one of the most democratic events in Goa’s history, because the common people were consulted and given options to choose from, in terms of preserving their unique identity. Our regional identity is composed of a range of factors that include our eating-drinking habits, love for music and dance, craze for football and bullfights, folklore and more importantly, our language, Konkani.

Unfortunately, when states were formed on the linguistic basis, Goa, homeland of Konkani, was under colonial rule and hence, remained out of bounds as far as the Constitution of India was concerned. Soon after the liberation, our identity was threatened when expansionist forces across the borders staked claims over our territory. The ‘67 Opinion Poll gave the newly liberated but skeptical people the much required reassurance that they were welcome in the newly affiliated country to voice their choice. Our democratic victory at the Opinion Poll, where we displayed our strong ethnic solidarity, laid a sound foundation for the secular regional identity of Goans. Goa is traditionally known for its communal harmony. However, after the recent rise of majoritarianism, we see a certain discernible trend in the state’s social structure that can be seen as an inclination towards strong communal polarisation.

Also Read | Writers Must be Fighters: Damodar Mauzo

Most diasporic Hindus are vocal and respond positively to the Hindutva agenda, while the Catholic counterpart, who perceive this as a threat to their religious identity, is equally voluble venting their anxiety over growing religious intolerance. Regional identity assumes larger significance today when religious identity overrides.

MR: Goa’s history is also the history of Konkani, which, as you’ve mentioned in your book Ink of Dissent, has helped shape up a “Goan sensibility”. Considering the Sangh’s recent attempts at homogenisation along the lines of a single national language for the entire country, how do you locate Konkani’s significance?

DM: Hindus and Catholics are the two major communities in Goa and their strongest common bond is their language Konkani. It is to the credit of Goans, especially the Catholics, that our mother tongue alive today, despite an absolute ban on it by the Portuguese (1684 Decree). Even after our liberation, the Goan people had to take to the streets to fight for their language. Ultimately, through a 555 days-long agitation, which turned violent towards the end, the law to make Konkani the Official Language of Goa was passed in February 1987.

Just as Konkani was starting to make its presence felt in the mainstream with a pulsating stream of literature and vibrant popular theatre, the current government has hinted at language homogenisation which would mean that Hindi would be thrust upon the people of India as the only or main official language. This is yet another attempt by the sangh to push their agenda of propelling monoculture – a dangerous move that can easily take a toll on regional languages. Through this, a false notion of a homogeneous national culture is being mooted, which is a direct threat to our linguistic diversity. Konkani, being the language only of a few millions is put in a dangerous situation. Any hasty decision to relocate Hindi’s present position in the country and belittle the regional languages can create a North-South divide perilous to the integrity of our country. The imposition, if any, is certain to lead to a massive popular agitation.

MR: Your name is on the “hit list” of the Sanatan Sanstha, the Hindutva outfit booked for the murders of Dabholkar, Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh. You’ve been a vocal critic of the group since the Goa bomb-blasts of 2009. How is living with relentless threats to life and constant police protection? Do you think regional language writers are under a greater risk when it comes to Hindutva’s attacks?

DM: It is indeed an embarrassment for any writer to move about with a gunman wherever we go – be it a literary meet, wedding or funeral. Thankfully, the escort is mostly in civil dress making himself unobtrusive. I have to take him along in my car or make him run alongside me as I take a morning walk. I also have to sacrifice my privacy. Besides the PSO, there is a policeman in uniform on guard at the door, supposedly a deterrent to the probable hitman, but often ends up being a repellent to innocent visitors who shy away from entering the house, wary of confronting the cop.

Initially, envisaging all this, I had refused to accept the security. I never felt insecure nor did I feel threatened by the death threat. But then the state security agency was apprehensive of being called negligent in case any untoward was to happen. So I relented. Now I put up with them.

During the investigation that took place after the assassinations of Dabholkar, Pansare, Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh, a hit-list maintained by the suspected killers were found, wherein my name also figured. The Union Home Ministry then alerted the state government and soon after, the Intelligence stepped in to brief me about the threat. Ever since then, 25th of July 2018, to be exact, I have been provided with round-the-clock police security.

Recently, once again when I requested them to withdraw the security, they said it is up to the Review Committee to decide.

Also Read | The Invisible Threat: Damodar Mauzo

As a writer, I consider it my duty to speak and write against any disruptive incident or phenomenon not in the interest of the society. The Sanatan outfit headquartered in Goa espouses Hindutva fundamentalism which, I believe, is detrimental to the well-being of our country in general and Goa in particular. Fortunately, the divisive forces got exposed in 2009 they attempted to bomb a Diwali event, when some political leaders in the then government managed to puncture the proceedings. As I have been vociferous about this in and outside Goa, obviously, fundamentalist elements, who brand people like me as durjan, were infuriated.

Needless to say, freedom of expression in the country has been in jeopardy ever since Hindutva forces have claimed power. The number of writers, mostly regional, who are threatened, is growing. Jharkhand novelist Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar whose book was banned and himself suspended from his government job or Malayalam writer S Hareesh who was forced to withdraw his novel following the Sangh’s protests are a few among them. Fundamentalists are more wary of regional writers and their literature because their outreach is wider than that of English language writers. I’ve also noticed that Hindutva fanatics perceive greater threat from liberal Hindus rather than fundamentalist non-Hindus. This is why they are constantly trying to target liberal Hindu writers.

Also Read | Damodar Mauzo: “Indian writers have always stood by their right to freedom of expression…”

MR: As a spin off from the chapter “Writers Must be Fighters” of your book, Ink of Dissent, do you feel it important for writers and artists, in particular, to get involved in debates around freedom of expression and murder of dissent in this country, and why?

DM: Genuine writers are liberal in their views, for they believe in respecting others’ views, while fearlessly expressing their own views too. No writer can be anti individual freedom, which is inclusive of freedom of expression and also the right to dissent. In what we call the “world’s largest democracy”, we cannot afford to suppress the voice of dissent! Does the writers’ responsibility end after dutifully exposing societal inequalities? Is it not important for writers to rise to the occasion when the marginalized fall prey to the malevolent designs of the people at the helm? Aren’t writers duty-bound to express solidarity when fellow writers are persecuted by the regime? Yet, when the likes of Romila Thapar, Keki Daruwalla or Ramachandra Guha are trolled by supporters of Hindutva, we hardly hear writers, barring a few, expressing solidarity.

I feel sick when some writers and journalists blame agitating Dalits, in the case of Bhima-Koregaon, for instance. Is it fair to comfortably sit on one’s armchairs and criticise the rallying oppressed for taking to the streets? By arguing against them or even by maintaining silence don’t we realise that we further condemn the condemned? Have we given up questioning? Why don’t we inquire into the involvement of the Telugu poet Varavara Rao? Is he anti-national simply because he sides with the oppressed? I hardly see any debate taking place amongst writers over the arrest of the members of our fraternity. Except for a handful of writers who protested over the Sahitya Akademi’s silence over the assassination of its member M M Kaburgi, others dont seem to have taken cognisance of such happenings. I strongly feel that writers must get into public debates and challenge the brazen state repression on freedom of expression, before our free voices get literally choked.

Also Read | Why Sanathan Sanstha’s Allegation is Redundant

MR: How active has the Goan civil society been in terms of participation in debates regarding attacks on dissent under the present regime?

DM: The Goan civil society is very vibrant and vocal when it comes to issues that plague our society. Be it students’ activism, green activism, animal activism, the Goan people are on the frontline. Debates do happen, but by nature, Goans are not the kind to take to the streets unless. In 1986, for the first time in the history of the state, nearly a hundred thousand people from all over the state gathered in Panaji to participate in the mass rally demanding Official Language status to Konkani. However, it did not happen when ten Congress MLAs ditched the electorate overnight to switch their allegiance over to BJP recently. When the media announced the threat to my life, hundreds gathered to express solidarity with me and the demand to ban Sanatan Sanstha was voiced by many. We organised a talk by scholar and civil rights activist Anand Teltumbde in the face of the warrant issued to him as part of the Bhima-Koregaon controversy. We also brought singer-activist T M Krishna to the state who spoke on the right to dissent. We held a national event under the banner of Dakshinayan Abhiyan Goa that was attended by over 600 people. My book Ink of Dissent was launched by historian Ramchandra Guha in the presence of around four hundred people.

Goans are quick to react to any anti-social move. However, I sense some sort of despair among intellectuals here after the BJP has come to power with a thumping majority, which needs to be addressed. We need to look for alternatives to Hindutva’s brand of politics. Hopefully, there’s some change the next time we will speak.