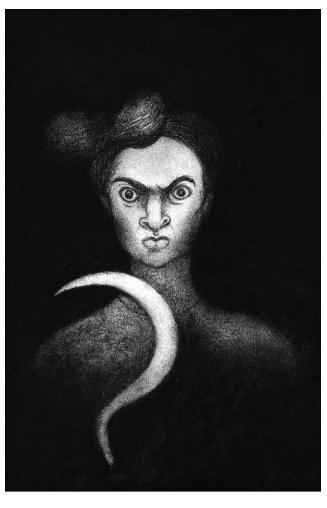

Historian Manu Pillai’s recently published book The Courtesan, the Mahatma & the Italian Brahmin: Tales from Indian History seeks to revisit many characters from the country’s past – from Basava and Nangeli to Phule and Macaulay – in three elaborate parts. The work also contains striking illustrations by animation film maker and illustrator Priya Kurian. Here is an excerpt from the chapter The Woman with no Breasts of the book, wherein Pillai takes a relook at the story of early 19th century Travancore’s Ezhava woman Nangeli who cut off her breasts in protest against the regressive caste-based ‘breast-tax’ of the time. Pillai asserts that it was not Victorian modernity-influenced ideals about modesty or disgrace about one’s bare body that prompted this 19th century Malayali woman to this act, but her revulsion towards the social order itself, against caste and feudalism.

Read on to know how Manu Pillai reads Nangeli.

The tale of Nangeli that they will tell you today has her fighting to preserve her honour, where honour is construed as her right to cover the breast. But in Nangeli’s time, the honour of a woman was hardly linked to the area above the waist. As F. Fawcett remarked, dress was ‘a conventional affair, and it will be a matter of regret should false ideas of shame supplant those of natural dignity such as one sees expressed in the carriage and bearing of the well-bred … lady’.

But the import of Victorian patriarchy also imported shame, and women were told that a bare body was a mark of disgrace. Dignity lay in accepting male objectification; honour was located in docility. Men, studying in colleges in big cities, received jibes about their topless mothers who may have had more than one husband. Could they ever be sure about who their fathers were? These men dragged into Kerala the masculinity of their patriarchal interlocutors, and women too, exposed to the West and a new conception of femininity, succumbed. ‘We will publish nothing related to politics,’ declared one of the region’s earliest women’s magazines in 1892, adding that ‘writings that energise the moral conscience’—tips on cooking, stories of ‘ideal women’— and ‘other such enlightening topics’ alone would be covered. A lady’s job was in the home as a mother, as a loyal wife and housekeeper, not outside as a topless harlot who exercised her customary right to divorce. ‘As women,’ another declaration went, ‘our god-ordained duty is the care of the home and service towards our husbands.’

Also Read | Revisiting the Popular: Mukulika R in conversation with Manu Pillai

New icons needed to be found—women who fit the bill of the new order rather than those who were emblems of a now disgusting bare-bosomed past. And where such womenwere in short supply, existing women were reincarnated, as J. Devika has shown. Umayamma of Attingal, the topless queen whom the Dutch noted for her ‘noble and manly conduct’, who was ‘feared and respected by everyone’, and who was a ‘young Amazon’, became in S. Parameswara Iyer’s poetry a melodramatic damsel in distress, a helpless mother (when, in fact, she had no children) pleading for a male protector. Where once the English had (with perhaps some exaggeration) reported that the ‘handsomest young men about the country’ formed her seraglio and ‘whom and as many [men] as she pleases to the honour of her bed’ could be had by her, now she became a loyal, patriarchal icon of womanly virtue. The women of the past were turned into ciphers for the present, filled with doses of honour and draped in garbs tailored by men. The wheels of time had turned and this is what was needed for a changing society in Kerala.

New icons needed to be found—women who fit the bill of the new order rather than those who were emblems of a now disgusting bare-bosomed past. And where such womenwere in short supply, existing women were reincarnated, as J. Devika has shown. Umayamma of Attingal, the topless queen whom the Dutch noted for her ‘noble and manly conduct’, who was ‘feared and respected by everyone’, and who was a ‘young Amazon’, became in S. Parameswara Iyer’s poetry a melodramatic damsel in distress, a helpless mother (when, in fact, she had no children) pleading for a male protector. Where once the English had (with perhaps some exaggeration) reported that the ‘handsomest young men about the country’ formed her seraglio and ‘whom and as many [men] as she pleases to the honour of her bed’ could be had by her, now she became a loyal, patriarchal icon of womanly virtue. The women of the past were turned into ciphers for the present, filled with doses of honour and draped in garbs tailored by men. The wheels of time had turned and this is what was needed for a changing society in Kerala.

Also Read | The Past Still Infects the Present: Ishita Mehta in conversation with Srividya Natarajan

Nangeli too was recast. When Nangeli offered her breasts on a plantain leaf to the rajah’s men, she demanded not the right to cover her breasts, for she would not have cared about this ‘right’ that meant nothing in her day. Indeed, the mulakkaram had little to do with breasts other than the tenuous connection of nomenclature. It was a poll tax charged from low-caste communities, as well as other minorities. Capitation due from men was the talakkaram—head tax—and to distinguish female payees in a household, their tax was the mulakkaram—breast tax. The tax was not based on the size of the breast or its attractiveness, as Nangeli’s storytellers will claim, but was one standard rate charged from women as a certainly oppressive but very general tax.

When Nangeli stood up, squeezed to the extremes of poverty by a regressive tax system, it was a statement made in great anguish about the injustice of the social order itself. Her call was not to celebrate modesty and honour; it was a siren call against caste and the rotting feudalism that victimised those in its underbelly who could not challenge it. She was a heroine of all who were poor and weak, not the archetype of middle-class womanly honour she has today become. But they could not admit that Nangeli’s sacrifice was an ultimatum to the order, so they remodelled her as a virtuous goddess, one who sought to cover her breasts rather than one who issued a challenge to power. The spirit of her rebellion was buried in favour of its letter, and Nangeli reduced to the sum of her breasts.