There are multiple lessons to be drawn from the conduct and experience of Furqan Ali and his schoolchildren. None perhaps more significant than the need to harness the everyday togetherness of religious communities to counter the Sangh Parivar’s politics of hatred, which seeks to demonise Muslims as anti-national and isolate them.

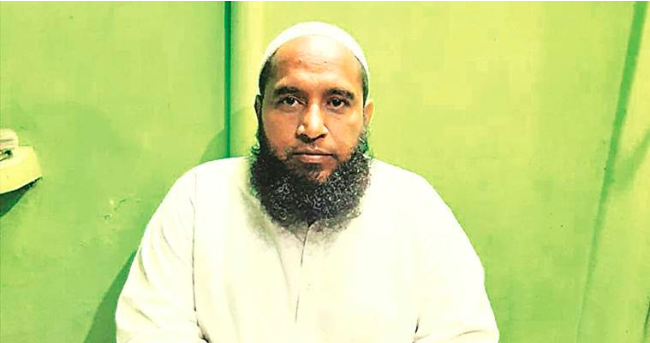

For those late on the story, here is a recap: Furqan Ali was the headmaster of the Ghayaspur primary school, in Bilaspur block of Pilibhit district, Uttar Pradesh, until he was suspended last week. The order for his suspension was issued after the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, an affiliate of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, claimed that the Ghayaspur primary school’s morning assembly ritual included the recitation of a religious prayer.

In reality, though, Ali would have the schoolchildren recite Lab pe aati hai dua, a poem by Muhammad Iqbal, popularly known as Allama Iqbal, who also wrote the famous Saarey jahaan se achccha. The poem does not qualify as a religious prayer.

Either out of ignorance or with the purpose of sparking a controversy, the VHP and the Hindu Yuva Vahini, a Hindu militant group founded by Chief Minister Adityanath in 2002, organised protests outside the school and the district collectorate to demand the removal of Ali from the post of headmaster forthwith. A hasty inquiry found that Ali had violated government rules.

Basic Shiksha Adhikari Devendra Swarup’s order suspending Ali said, “As per a viral video on social media, it came to our knowledge that at Primary School, Ghayaspur, students are being made to sing a different prayer other than the commonly accepted one… Furqan Ali prima facie has been found responsible for this and thus has been suspended.”

The events leading to Ali’s suspension demonstrates the clout that the Hindu Right groups wield over the Uttar Pradesh administration, which is inclined to accept their allegations as true even though they are infamous for concocting lies.

These groups have to be appeased presumably because of the support they enjoy from the Bharatiya Janata Party government in Lucknow. The Furqan Ali episode underlines how power is employed to establish ideological dominance.

It also tells us about the change in the method to trigger rage and engineer a social rift. In this endeavour, rumour had always been a deadly tool. However, rumours spread through word by mouth always lacked the quality of evidence. These were often scotched before acquiring the veneer of truth.

This lacuna has been plugged by videos readily accessible on mobile phones. By his own admission, Swarup and others became aware of Ali’s transgression through a video. It did not occur to him that the video could have been doctored to achieve a nefarious goal. Or was it a case of manufacturing evidence to get rid of a person whom the Hindu Right detested?

However, the Sangh Parivar’s strategy of widening the social chasm failed because it could not penetrate the bulwark of everyday togetherness that bound Ali to the schoolchildren. It was the schoolchildren who told the media that they used to recite Iqbal’s Lab pe.. in the morning assembly and not a religious prayer; that the poem was prescribed in their syllabus; that it was they, Hindu and Muslim students alike, who had requested Ali to include Iqbal’s poem in the morning assembly ritual.

The counter-narrative of the schoolchildren compelled the administration to revoke the suspension of Ali. But he wasn’t reinstated as the headmaster of the Ghayaspur primary school; he was shifted to another school. This was a face-saver for the Hindu Right groups, for whom the administration scripted a Pyrrhic triumph.

Yet, in the era of the politics of hate, even the revocation of Ali’s suspension needs to be trumpeted—and credited to the deep bonds forged between the headmaster and his schoolchildren. They praised Ali for spending his own money to buy vegetables for supplementing the mid-day meals; how he never hit them; and how he almost always acceded to their wishes.

It was this everyday bonding that the Hindu Right could not severe, evident from the sharp dip in the attendance at the Ghayaspur primary school in the days following the suspension of Ali. As Kavita, whose children are admitted in what was once Ali’s school, said, “The administration is playing with the future of our children. They don’t care about our children because we are poor.”

The Ghayaspur primary school’s push-back against the Hindu Right conforms to what Ashutosh Varshney, professor at Brown University, writes in Battles Half Won: India’s Improbable Democracy, “The pre-existing local networks of civic engagement between the two communities [Hindus and Muslims] stand out as the single most important proximate explanation for the difference between peace and violence.”

Places less likely to witness communal rioting are those where the networks of Hindu-Muslim engagement are varied and deep. Such networks are of two types: everyday forms of engagement and associational forms of engagement. The latter, mostly found in cities, include traders’ association, trade unions, clubs, including the Lions and Rotary Clubs, art-lover’s association and organisations such as porters and rickshaw-pullers’ associations.

Varshney spells out the difference between the two networks and the quality of engagement these foster. “At the village level in India, everyday face-to-face engagement is the norm, and formal associations are few and far between. Yet, rural India…has not been the primary site of communal site of violence,” Varshney writes on the basis of empirical research he conducted around 1994-1995.

“By contrast, even though associational life flourishes in cities, urban India…accounts for the overwhelming majority of deaths in communal violence between 1950 and 1995.” Varshney points out.

Cities susceptible to communal violence are precisely those where the inter-community engagement does not run deep. Associations can bolster everyday togetherness not invent them. Varshney cites the contrasting response of Calicut, in Kerala, and Aligarh, in Uttar Pradesh, to the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992. Aligarh imploded; Calicut did not, even though Muslims comprised 36%-38% of the population in both cities.

In his survey, Varshney found that the engagement between Hindus and Muslims in Calicut and Aligarh was of remarkably different quality. Nearly 83% of Hindus and Muslims in Calicut often ate together in social settings; only 54% in Aligarh did. About 90% of Hindu and Muslim families in Calicut reported that their children played together, in contrast to just 42% in Aligarh. Again, nearly 84% of Hindus and Muslims in Calicut visited each other; in Aligarh, only 60% did, and “not often at that.” This was a significant reason why Calicut did not erupt in 1992.

Since the 1990s, communal mobilisation has undergone significant changes. For one, it is not episodic but a continuous attempt at keeping the communal cauldron to simmer, occasionally letting it bubble over. For the other, the Sangh’s myriad outfits have struck roots in rural India, straining communitarian relationship that has been under stress because of agrarian distress and economic liberalisation policies. Add to these worries the bureaucracy’s increasing tendency to mollycoddle the Hindu Right hotheads, all because the BJP is in power.

Yet the exemplary conduct of Ghayaspur’s schoolchildren suggests that Varshney’s prognosis on why certain places are more susceptible to communal animosity than other places is as relevant as it was two decades ago. Engagement between Hindus and Muslims becomes, in a way, a natural bulwark against communal mobilisation.

Indeed, Furqan Ali and his schoolchildren have brought to the fore the pressing need to nurture and protect the everyday togetherness of Hindus and Muslims from being corroded by the Sangh’s hate ideology. Harried Opposition leaders must learn from the headmaster and his children how to build an anti-Hindutva laboratory.