For a mouth-watering meal, smoked pork stirred with axone (akhuni) — fermented soya bean paste with chives, bamboo shoots and ghost pepper — is irreplaceable. In director/writer Nicholas Kharkongor's film, Axone, these become ingredients for chaos. Kharkongor visualises food as a metaphor for belonging and ethno-nationalism. Those attempting to cook are friends who live and eat together and primarily belong to communities who live in the northeast side of India. They form a myriad cast going about their everyday lives as aromas of the piquant axone spreads through the neighbourhood.

The beginning shots open on the panopticon called New Delhi. It is truly gratifying to follow Parasher Baruah's camera through Delhi's Humayunpur. There are many small worlds we are invited to observe. Hurrying down the alleys, we have our protagonists holding hands, confronting bullies, peddling food and ideas. Here a Punjabi family that lets out rooms to tenants from Africa and various states of the northeast India. It is a truly transnational migrant enclave.

The film brings to fore a satire on racial exclusion in the Indian metropolis at one level, and a yearning and projection of individual desire and expectations from their present lives on another. This makes Axone a well-woven narrative about the experiences of a migrant generation, eager to recapture their own lost youth in their homelands. They find that in David Larammawia's graffiti—marked walls, small popular eateries, and in each other—which is why cooking the Axone together is important.

There is one scene that stood out for me – my own tower of Babel. We see Minam's friends desperately trying to convince someone, anyone, to share a space for a few hours so that this malodorous food can be cooked. The Axone is being cooked for Minam's special day. They speak in different tongues that inexplicably reflect the multicultural belonging and sense of community, as well as the anxiety of social exclusion. The emotions that pour out of these women and men cannot be contained in Hindi and English – they take form of Meiteilon, Nepali, Kokborok, Axomiya, Nagamese, even Bengali and Punjabi. And as Kharkongor informed his audience after the sreening, this was a handful of the 200 tongues that are spoken in the northeastern states, some of which are now endangered or almost extinct.

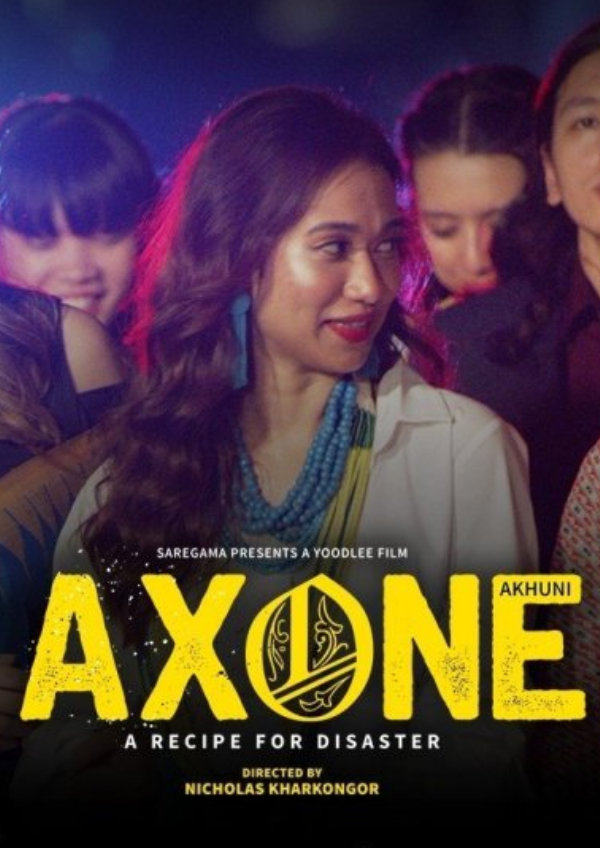

The film rides on the able shoulders of Lin Laishram as Chanbi and Sayani Gupta as Upasana, both of who are splendidly complemented by Tenzin Dalha playing Zorem and Lanuakam Ao as Bendang. Gupta's quiet exuberance and Laishram's measured delivery, even in the most complex scenes, are a significant feat. Dalha's simplicity gives the film a beautiful energy. Lanuakam's embittered expressions convey every experience a migrant may feel away from home. Dolly Singh Ahluwalia, Vinay Pathak and Rohan Joshi play the many shades of the landlords in Delhi caught in a bind. In a rare role, Adil Hussain closely observes the neighbourhood through the day. Asenla, whose character is mostly present in her absence, and who holds all friendships and arguments together, plays Minam. Merenla Imsong, who plays Balamon delivers an important line with candour, “if we all look the same, how do you know when a different northeasterner knocks on the doors of your neighbour?”

We do not ask much of our neighbour, let alone neighbouring states. Living in a JNU hostel almost a decade ago, I remember a bevy of guards and the hostel warden marching towards my neighbour's room to find her heating nakham bitchi. Amidst laughter, a guard compared the overpowering aroma of fermented fish to the odour from a drain—a statement that is both ignorant of regional traditions and offensive at thesame time. In a similar vein, the film's reference to Arunachal Pradesh's Nido Tania's lynching and subsequent death in 2014 in New Delhi contributes to an important sub-plot on physical offence against individuals we refuse to identify with. At present it belongs to a continuum of violence that is based primarily on ideas and identity markers of social exclusion. Tajdar Junaid's soulful background music may erase the memories of violence momentarily. When the wedding party steps onto the street with Mangka Mayangbalam's powerful voice praising divinities in a traditional Meitei song, it felt as if the metropolis has come to a standstill as they gazed at the shimmering stars from the hills and the valleys.

The author of the review attended the World Premiere at the BFI London Film Festival on October 2. Axone is scheduled to be screened at the Mumbai Film Festival on October 19, 21, 23 2019.