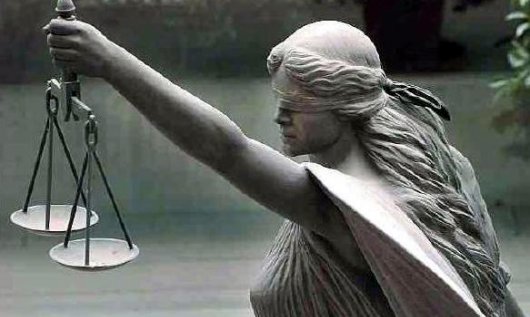

In a world where natural resources are getting depleted and emissions from pollution are being produced faster than the blink of an eye, citizens and bureaucrats are pitting against each other to save the environment. While citizens adopt conservation and ancient wisdom to save the environment, bureaucrats adopt creating an infrastructure to save the environment. One thing common in the two antagonists views is science. In this war of science vs science, it is the law that has to play an arbitrator.

The science that citizens take recourse to save the environment involves increasing efficiency by optimisation of resources, a trait inspired by nature. Cactus, a plant designed to flourish in the desert has its leaves modified into spines to reduce transpiration and stem modified to store water. The resource, water has been optimised to ensure that its scarcity doesn’t affect the process of photosynthesis, thus achieving maximum efficiency. In this process, cactus doesn’t harm any other living being, on the contrary, helps desert insects by providing them with moisture and food. The products, processes, and policies thus developed with this kind of science are coherent with a healthy planet. An example of nature-inspired science is the organic farming whereby increasing the fertility of the soil, adopting indigenous seeds, bio fertilisers from plant and animal waste not only increases the yield of crops but lowers environmental impact per produced unit.

The science that bureaucracy adopts largely consists of developing technology, mitigation measures and constructing infrastructure to fight climate change. For example, pest-resistant variety of seeds developed by genetic engineering does increase the yield of the farm but destroys the biodiversity and damages the soil fertility.

When Judiciary is summoned to outweigh one science over the other, one factor that matters more than the data, studies, reports and researches is the “discretion” of the judiciary. This discretion is the single most factor that safeguards the judicial system from the tsunami of automation that is encapsulating every single industry. If mere numbers and figures were to decide the outcome of a conflict, we can have computers or robots to give the judgements. Judgement is one place where human intellect gets to prove its supremacy over the complex data that is devouring its instinct, common sense and most importantly benevolence.

This discretion relies heavily on the sharp ‘surveillance’ and ‘knowledge’. When the discretion is called for countervailing one science over the other, the knowledge of science becomes inevitable. Science doesn’t come with conditions. Science is the solution to overcome conditions. For example, The avant-garde engineering marvel of Mumbai Metro fails to save the massacre of 2700 trees! The science behind one of the world’s largest public transport system is not only unable to find alternative sites other than a forest area for a car shed but also unable to use an open site of Kanjurmarg proposed as an alternative. It is only the discretionary ability of the judiciary that helps to dissect whether it is the intent of the science or bureaucracy which proposes to fragment a forest, threatens the survival of biodiversity, displaces indigenous tribals, pollutes the groundwater, and exacerbates pollution.

Besides, surveillance and knowledge, a very important aspect which empowers this property of discretion is the’ vision’ of the judgement. In the long term, what are the implications of the judgement on the future generations determines the direction of the judgement. This ‘vision’ of the judgement prevents the judgement from becoming short-sighted and saves time and resources from encouraging newer petitions. For example, The judgement in the case of the issue of building a car shed in Aarey forest should not be limited to the land use or project feasibilities. But it needs to be visionary and should be able to foresee the future implications of fragmenting a forest, threatening biodiversity, increasing vulnerability to commercial exploitation and permanently changing the topography of a city.

The world is fighting climate change where citizens are fighting climate change on the streets, bureaucrats at the summits and conferences, businesses at research and innovation laboratories, and consumers at retail outlets and homes with eco-friendly choices. Has global judiciary too been a part of this movement?

In the first successful case of its kind, a judge in the Hague has ruled that the Dutch government’s stance on climate change is illegal and has ordered them to take action to cut greenhouse gas emissions by a hefty 25% within five years. In another historic verdict pertaining to Amazon forest, the panel of three judges permanently nullified the consultation process with the indigenous Waorani tribe undertaken by the Ecuadorian government in 2012 and indefinitely suspends the auctioning of their lands to oil companies. Similar cases against deforestation in the Philippines and a supreme court ruling in India that paved the way for Delhi’s buses to switch from diesel to compressed natural gas (CNG) to cut air pollution are examples of how judiciary has participated in fight for climate justice by ordering the government to protect its citizens from climate change.

Europeans are more worried about climate change than unemployment, the economy or terrorism, according to the latest Eurobarometer survey. The data were gathered before the record-breaking temperatures across much of Europe last month and reports of the largest single-day loss of Greenland’s ice sheet. With 17% of the world population and just 2.5% landmass and 4% of water share, India is standing on the verge of a major climate catastrophe. It has one of the highest densities of economic activity in the world, and very large numbers of poor people who rely on the natural resource base for their livelihoods, with a high dependence on rainfall. According to the Composite Water Management Index (CWMI) report released by the Niti Aayog in 2018, 21 major cities (Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad and others) are racing to reach zero groundwater levels by 2020, affecting access for 100 million people. According to data available on the website of Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, between 2010 and 2016, the country witnessed a total of 178 heatwave bouts, but in 2017 alone India suffered 524 heatwave spells. According to a 2017 study by British medical journal Lancet, India topped the world in pollution-related deaths, accounting for 2.5 million of the total 9 million worldwide in 2015. By 2020, pressure on India’s water, air, soil, and forests is expected to become the highest in the world.

While the bureaucracy is largely responsible for preventing and mitigating the climate change, there is a need for equal participation of economists, engineers, scientists, citizens and communities to get involved into policymaking and means of implementation. In an indirect democracy like India where laws are not formed directly by the people but the elected representatives, it is only the efficient judiciary that empowers citizens and communities to stand parallel to the decision-makers and not only makes their voices heard but materialises them into a strong action.