Translation is not just about words, it is about carrying a culture, a history, a whole world into another language. Translations do not just bring languages closer to one another, they also introduce us to diverse modes of imagining and perceiving different cultures.

To mark the International Translation Day, celebrated on 30 September, the Indian Cultural Forum will be doing a series of posts to emphasise the power and importance of translations.

“Everything is finished, nothing remains.”

I must force silence to be a mirror…

It’s raining as I write this. I have no prayer.

It’s just a shout, held in, it’s Us! It’s Us!

Whose letters are cries that break like bodies

in prisons… (“The Country Without a Post Office”, 204-205)1

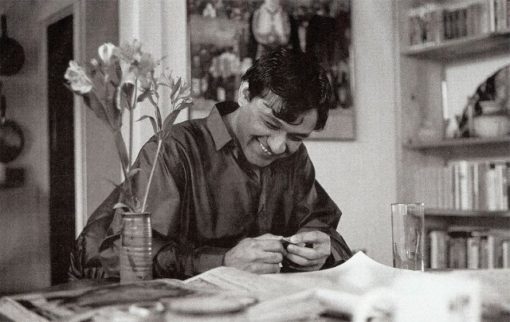

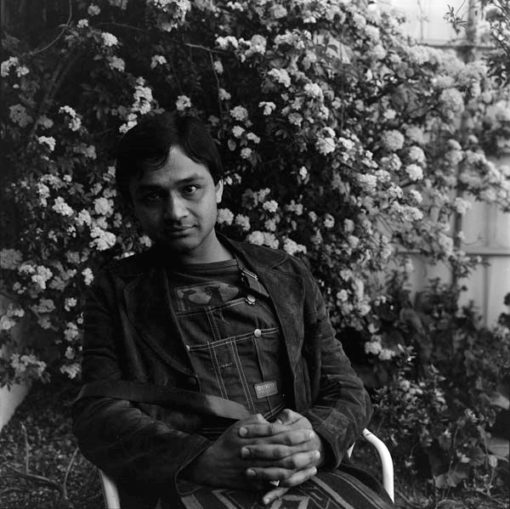

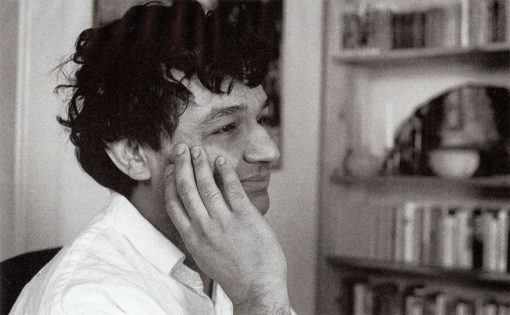

Agha Shahid Ali’s lines pulsate with a sense of urgency that feels uncannily appropriate at this juncture in history. He, like his poetry, was someone who eluded boundaries. “I am a dealer in words/ that mix cultures,” he says in his poem “Dear Editor”. Moving to the United States from India in 1975, Agha Shahid Ali was born in New Delhi in 1949 and grew up in Kashmir for most of his childhood. Yet even as landscapes of America and India, New Delhi and Brazil, Uruguay and Chechnya are jostled alongside one another in a state of constant flux in his poetry, it has always been grounded in Kashmir.

Let me cry out in that void, say it as I can. I write on that void: Kashmir,

Kaschmir, Cashmere, Qashmir, Cashmere, Qashmir, Cashmir, Cashmire,

Kashmere, Cachemire, Cushmeer, Cachmiere, Cašmir. Or Cauchemar in

a sea of stories? Or: Kacmir, Kaschemir, Kasmere, Kachmire, Kasmir.

Kerseymere?2

A deep sense of loss echoes through his invocations that can be located in the litany of references about his homeland. Underneath it lies the long history of claiming “Kashmir” and the politics surrounding it.3

They make a desolation and call it peace.4

On March 1846, a treaty brought into existence the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir stitching together territories of Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh, Hunza, Nagar, Gilgit from the Sikh kingdom of Punjab to form the state. The parties involved: English East India Company and Gulab Singh, the raja of Jammu. With this, the earlier seamless and overlapping terrain of layered sovereignties had given way to the monolithic and territorial bounded one of the British and the new maharaja, Gulab Singh.5 The cumulative effect of this bounded territorialisation along with the strife for control of Kashmir between contending nations/powers has led to a conflictual coexistence becoming the everyday of lived experience in Kashmir. The sudden abrogation of Article 370 on August 5, 2019, the telecommunication and Internet blackout and the subsequent silencing of the Kashmiris is a step further in reducing Kashmir and its people to a territory in the larger discourse of the Indian Nation-State. Shahid’s writing bears witness and marks a resistance to such false attempts at unification that come at the cost of the lives of Kashmiris.

Srinagar hunches like a wild cat: lonely sentries, wretched in bunkers at the city’s

bridges, far from their homes in the plains, licensed to kill…while the Jhelum

flows under them, sometimes with a dismembered body. On Zero Bridge the

jeeps rush by. The candles go out as travelers, unable to light up the velvet

Void.6

As reports of a seething Kashmir slowly surface, Shahid’s words shatter the silence imposed on his beloved homeland. Poetry becomes a substitute for communication between Kashmir and the rest of the reading world; it is impassioned and ironic, instructive and perceptive as the language of paradox. As Kashmir becomes a “city that was robbed of every Call” the poet envisions the devastation of his homeland. “Nations don’t emerge as fully fashioned entities; they are created by states by flattening out of diverse languages, religions, cultures, through conscription, through education, and through coercion.”7 How does the idea of India — yours, mine, theirs, and ours — turn into a reterritorialization in denial about the existence of differences? How have our likes and preferences for a land, a language conjured up an abstract structure of this India? Could literary representation through Shahid’s poetry and writing give us a glimpse into this idea of India or the nation in relation to Kashmir?

Every headline read:

PARADISE ON EARTH BECOMES HELL

The night was broken in two by the Call to prayer

Which found nothing to steal but utter disbelief.

In every home, although Muharram was not yet here,

Zainab wailed. Only Karbala could frame our grief 8

Written in the tradition of the marsiya—an elegiac poem commemorating the martyrdom of Prophet Muhammad’s grandson and their family in Karbala (Iraq)— his poetry tackles the deficits of the history of nation building, bearing witness to the conspicuous absences, the unaddressed letters, countries without post offices, and missing people in this narrative. It mixes images of innocence and beauty that are juxtaposed with death, blood and terror to give grief a poetic significance and also to shock the reader out of inaction. Muharram through his poetry becomes—unlike a monolithic nationalism or pejorative communalism—a counter to disenchantment, a time to mourn but also rise in rage. It embodies a sense of the lived experience of the body in places ravaged by war. In the midst of political violence his poetry carries a charge to remind us how language itself is a luxury afforded mostly to the powerful and privileged. Shahid has an acute awareness of the deep-rooted connections between language and power and it is these connections he brings to light time and again in his poetry.

“The making of the nation involves the shaping of the Self, but also, therefore, the making of an Other. The geography of the nation is not so much territorial as imaginative, for it deals with what constitutes a people or a community, with ways the land has been lived on and worked over, with boundaries that include and exclude, with centers and peripheries…” 9 Shahid’s poetry fractures the nationalistic claims on Kashmir by showing us most persuasively this unstable, transformative, and political nature of borders, of the multiplicity of belonging and non-belonging. It bears a “trace” of extremity, becoming an event that mirrors the brutality that haunts “Freedom’s terrible thirst, flooding Kashmir”.

As Kashmir lies shackled under lockdown in the month of Muharram (which began September 1, 2019 this year) where “Son after son—never to return from the night of torture—was taken away” and “mass rapes in the villages, towns left in cinders, neighborhoods torched” stare at us, Shahid’s poems give us a glimpse into this turbulent everyday:

From windows we hear

Grieving mothers, and snow begins to fall

on us, like ash. Black on edges of flames,

It cannot extinguish the neighbourhoods,

The homes set ablaze by midnight soldiers.

Kashmir is burning…10

While the Indian nation-state claims to provide Kashmiris with an opportunity for full political education and mobilization, it also fuels institutional decay in Kashmir by muffling the institutions that engender popular political functioning to stem the threat of potentially separatist inclinations emerging from such training.11 What path is left for the people in the Valley to express their discontent or fulfil their aspirations then? Can poetry give us cues on tackling the homogenising impulse of the nation-state?

They ask me to tell them what Shahid means — Listen, listen:

It means “the Belovéd” in Persian, “witness” in Arabic.12

Shahid populates his poetry with a confabulation of voices. This layering with a multiplicity of meanings and understandings by Shahid is not an empty exercise but rather an act of defiance grappling with the continuing violence and erasure of voices. While Shahid experiments with form and language his poetry never loses an elegiac quality. It breaks with the pressure of grief and overflows in spite of the constraints of form that Shahid ties it with; it crumbles into fragments because of this tension, fragments that indicate a whole that refuses to be bound and closed of.

The prisons fill with the cries of children.

Then how do you subsist, how do you persist, Land?13

He allows his homeland to survive in a larger verbal and cultural matrix where it refuses to confine itself to the facets of the conflict alone. “Something of the beauty of Kashmir survives, if not in the land of today then the poet who writes about what it was.”14 His poetry has an intimacy with the collective while still retaining the personal. By mixing the syntax and forms of other languages and locations, Shahid transforms his homeland – translating Kashmir through Palestine, “By the Hudson lies Kashmir, brought from Palestine”15; realigning Srinagar with Sarajevo, Bosnia, Argentina, Paraguay, Chile and their respective struggles, all the while reinventing Kashmir. His poetry hints at the possibilities of plural and dialogic existence that refuses to be contained by singular monolithic identifications of the nation-state and its mechanizations. Rather it envisions varied alliances, reconciling in exile through Chinar trees and “the Jhelum’s waters so clean, so ultramarine”16, where “One day the Kashmiris will pronounce that word truly for the first time”.17

Shahid’s poetry reminds us of the close relation that exists between language, literature and history, especially in times of crisis. It bolsters our trust in literature and culture which even in the midst of a deafening silence burns with rage, wrestles against erasure, resists violence.

As Shahid would say,

The world is full of paper

Write to me.18

1. Unless otherwise attributed, all citations to Shahid’s verse refer to The Veiled Suite: The Collected Poems (2009, New York: W. W. Norton & Company), which includes his published poetry from six collections. The Half-Inch Himalayas through his final volume, Rooms are Never Finished, also including his book of ghazals, Call Me Ishmael Tonight.

2. “The Blesséd Word: A Prologue”, pp.171

3. The quote consists of terms used to refer to his homeland by outsiders/colonizers as opposed to the “native” Kashir.

4. A quote by Tacitus (speaking through a British chieftain regarding Pax Romana) that Shahid uses as a refrain in his poem “Farewell”, pp.175.

5. See Rai, Mridu. 2004. Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir. London: C. Hurst & Company Ltd.

6. “The Blesséd Word: A Prologue”, pp. 173-174.

7. Chandhoke, Neera. 22.08.2019. “State-breaking is not nation making”, The Hindu.

8. “From Amherst to Kashmir”, pp. 257-258.

9. Tharu, Susie and K. Lalitha (eds.). 1994. “Introduction” Women Writing in India. Vol. 2. New Delhi: OUP.

10. “I See Kashmir from New Delhi at Midnight”, pp.179

11. Ganguly, Sumit. 1997. The Crisis in Kashmir: Portents of War, Hopes of Peace. Cambridge University Press.

12. “In Arabic”, pp. 373.

13. “Land”, pp. 347.

14. Betts, Reginald Dwayne. 2017. “Borrowed Words: The Use of Quotations and Italics in the Ghazals of Agha Shahid Ali”. (ed.) Kazim Ali. Mad Heart Be Brave: Essays on the Poetry of Agha Shahid Ali. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

15. “Ghazal”, pp.297

16. “Postcard from Kashmir”, pp.29

17. “The Blesséd Word: A Prologue”, pp.172-174

18. “Stationery”, pp.71