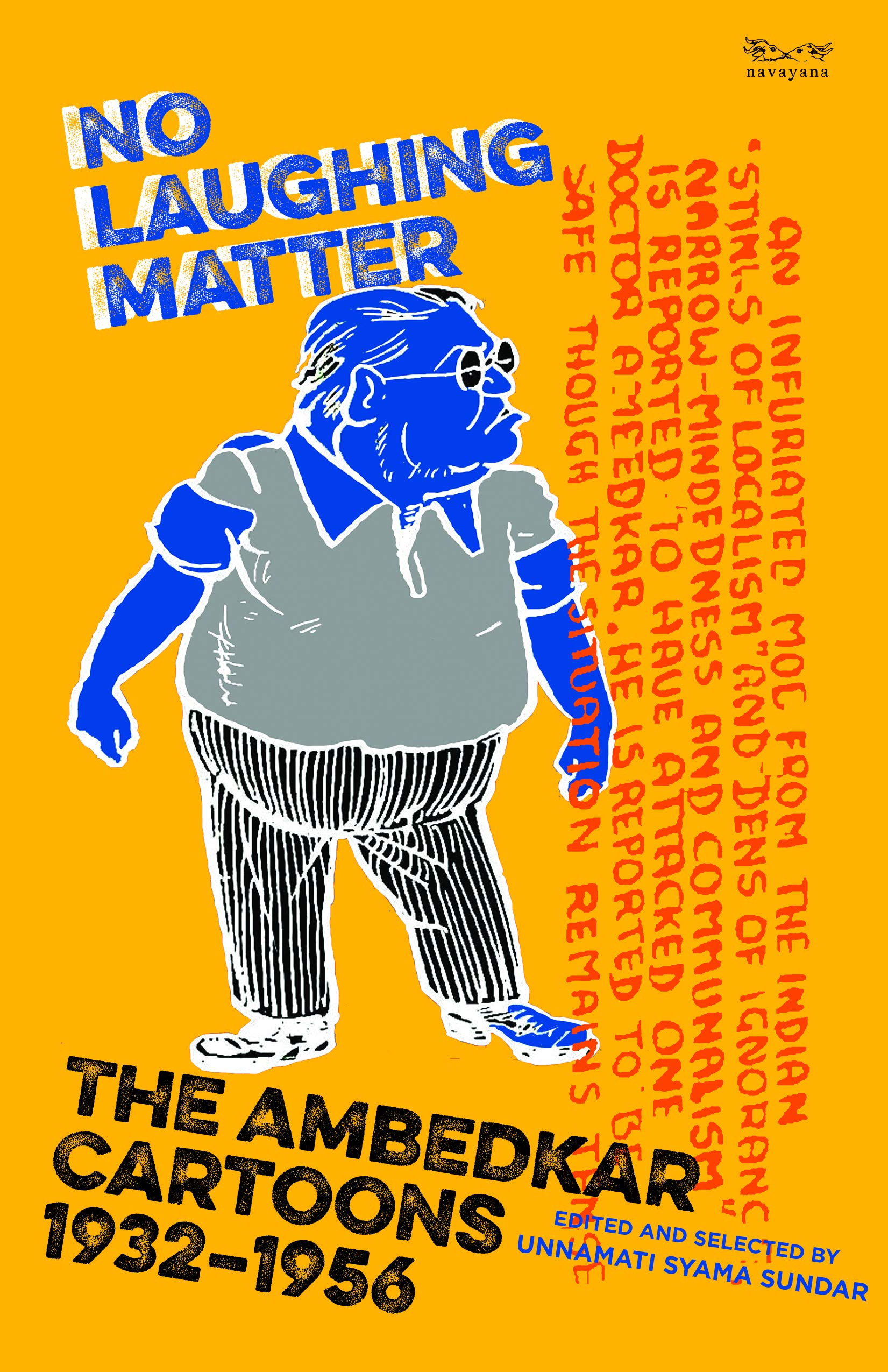

Image courtesy Amazon

Image courtesy Amazon

Research on colonial Indian cartoons and biographies of cartoonists is quite scant in India. Although cartoons provide an alternative visual history, they are often overlooked by academicians. Even premier institutions in India do not consider colonial cartoons a part of visual art history, nor encourage research on them. As a result, it is comics like Amar Chitra Katha and Chandamama that are more popular than colonial Indian cartoons, which focused on social evils.

Back in 2012, when the cartoon controversy erupted, I attended a meeting at the National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT), headed by Sukhdev Thorat at the time. The Thorat Committee had been set up to review all cartoons featured in NCERT textbooks. S Anand, the publisher of Navayana, took me to the meeting as a subject expert on colonial Indian cartoons.

The debate at the time was around a single cartoon of Bhimrao Ambedkar. Why not first look at other cartoons on him, I thought, and then came to a conclusion about his representation. I had already researched on colonial Indian cartoons and had naturally decided to archive the “Ambedkar cartoons”. When it started off, I was the only researcher working on this topic.

My journey began with a Navajivan Trust publication from the 1970s, featuring cartoons about Gandhi, after which I came across Don’t Spare me Shankar, a book dedicated to the cartoons of Jawaharlal Nehru. This is when I strongly felt that academic research had conveniently ignored Ambedkar all these years. Therefore, at the Gandhi Museum in Delhi, I started reading about Ambedkar and began chronicling the major events of his life and career – turning myself into an archivist of Ambedkar cartoons.

Ambedkar in the Public Domain

Initially, I was interested to examine how the colonial press represented Ambedkar on their publications. For this, I carefully went through colonial newspapers page by page, often widening my lens from just Ambedkar.

Those days, every time I came across a cartoon on Ambedkar, I would share it on social media for people to get a taste of these primary sources. My intention was also to expose the injustice done to Ambedkar, in colonial publications. All major Indian newspapers, periodicals and cartoons were studied and archived, over a period of about ten months.

After ten months, my friends advised against posting the images on social media, suggesting that I use the valuable data for research instead. I wanted to submit the cartoons as a report to the NCERT and Ministry of Human Resources Development (MHRD), however, the cartoon controversy ended before that, when the Thorat Committee removed Ambedkar’s cartoons from NCERT textbooks.

Usually when one visits the Archives, the staff enquires about the topic of research. I’ve realised that if one replies “Ambedkar”, it’s simply assumed that one belongs to the Dalit community, but if one says “Gandhi”, they attitude is always different. I’ve also noticed that archival material on Ambedkar would often be slightly ruined, with either the pages torn off or something scribbled on them. This is due to the sheer grudge that ‘upper’ caste Hindu scholars hold against him. The grudge seems to be due to reservations, for they haven’t even read him. [No Laughing Matter touches upon the issue of archiving subjects related to Dalit identity.]

Archiving took me to several places and libraries. Most of the cartoons featured in No Laughing Matter are from the microfilm archive at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) in New Delhi. I was still not satisfied. I visited the National Library in Kolkata, the Andhra Pradesh Archives and Research Institute in Hyderabad, Pune’s Film Institute Library and the Madras Archives in Chennai.

The visits were possible only because I had saved some of the money I received as part of the Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship. Even though in the final year of my PhD at the time, I felt archiving these cartoons was more important.

Not a Mere Cartoon-Collection

A mere compilation of cartoons was not enough. Cartoons need the support of strong annotations. I thoroughly went through the writings on Ambedkar, especially biographies. Thereafter, my quest was to discover how each of them represented Ambedkar. I also read his own writings and speeches, published by the Maharashtra Government Press. Juxtaposing all of this with newspaper reports and cartoons was the next step.

Towards the end, the process took on a Roshomon effect, as I searched for ‘truth’ in every possible source – for which I even studied the characters featured in the background of the Ambedkar cartoons. In other words, a compilation of Ambedkar cartoons is not just about Ambedkar. It also tells one about the colonial times in general – the Congress, the Viceroys and their Executive Council members, the drafting of the Constitution, the Hindu Code Bill etc. While working on my book, No Laughing Matter, I had compiled cartoons on the draft Constitution – specifically, to see how cartoonists of the time viewed the drafting process.

Cartoonists and their Priorities

During the later stages of my research, I felt that a biography of cartoonists was as important as their cartoons. As a result, I began to collect information about cartoonists from newspaper sources: their educational background, how they were trained as cartoonists and joined popular newspapers etc. Interestingly, only if they crossed a line were cartoonists removed from their field. Cartoonists such as Shankar (K. Shankar Pillai, founder of Shankar’s Weekly, whose 1949 Ambedkar sketches stoked the NCERT cartoon controversy in 2012) and Enver Ahmed are the best examples of this.

I compared how they depicted Ambedkar and other leaders, to understand the pulse of the times. Yes, during Partition, there were controversial sketches of Gandhi & Jinnah. Sukeshi Kamra, a post-colonial studies expert, in her book Bearing Witness, discusses the cartoons of this era. There was a cartoon on Gandhi sleeping with women, as part of the political rivalry between the Muslim League and the Congress party. Yet, the topics that cartoonists had chosen at the time surprised me to no end.

As is well known, Indian cartoonists had adopted the style of the legendary British cartoonist David Low, but they did not adopt his subtlety. They injected their casteism, misogyny and other perversions into these cartoons and they actively ridiculed caste, religious and gender identities.

Above all else, the cartoonist’s reverence for the British Raj and their loyalty for the Viceroys remained unchanged. They took extra care while drawing cartoons featuring British viceroys and were less careful—more careless—while drawing leaders who opposed the Congress and Gandhi. Indian cartoonist’s sketches on the draft Constitution and the Hindu Code Bill are the best instances of this and of their lack of sharp political ideas.

By the time my research ended, I realised that Ambedkar had always been ahead of his times. I also saw that the cartoonists in the popular press had no clue about his ideology. What illustrates this best is the fact that there is not a single cartoon depicting Ambedkar’s famous work, Annihilation of Caste, even though Gandhi had debated annihilation and even wrote counter arguments to it in his own paper, Harijan.

No other Dalit leader had the charisma Ambedkar at the time. Yet, the mindset of cartoonists remains the same as during Ambedkar’s time, and the best example of this was when cartoonists defended the controversial cartoon in 2012, in the name of “freedom of expression”.

We have a poor sense of history. We lag behind in historical research. Our archival sources are not well-protected. We need a separate cartoon library or museum. If there was such spaces, the Ambedkar cartoon controversy would have never erupted.